For decades, human rights organizations and families of people who disappeared amid Colombia’s internal conflict have pointed to La Escombrera, a trash dump in the western hills of Medellín, as the site of a mass grave with possibly hundreds of bodies buried beneath the rubbish.

Following months of searching which began in July 2024, and 36,000 cubic meters of dirt removed, on December 18, Colombia’s Unit for the Search of Disappeared Persons (UBPD) announced it had found the first set of human remains at the dump’s excavation site.

“We have found the first bone structures in La Escombrera. Now, it is imperative to collect biological samples from the searching families to carry out genetic analyses and encourage the identities of the deceased, in order to deliver the culturally-relevant information to the public, dignifying victims’ memory,” stated Luz Janeth Forero, the UBPD’s director.

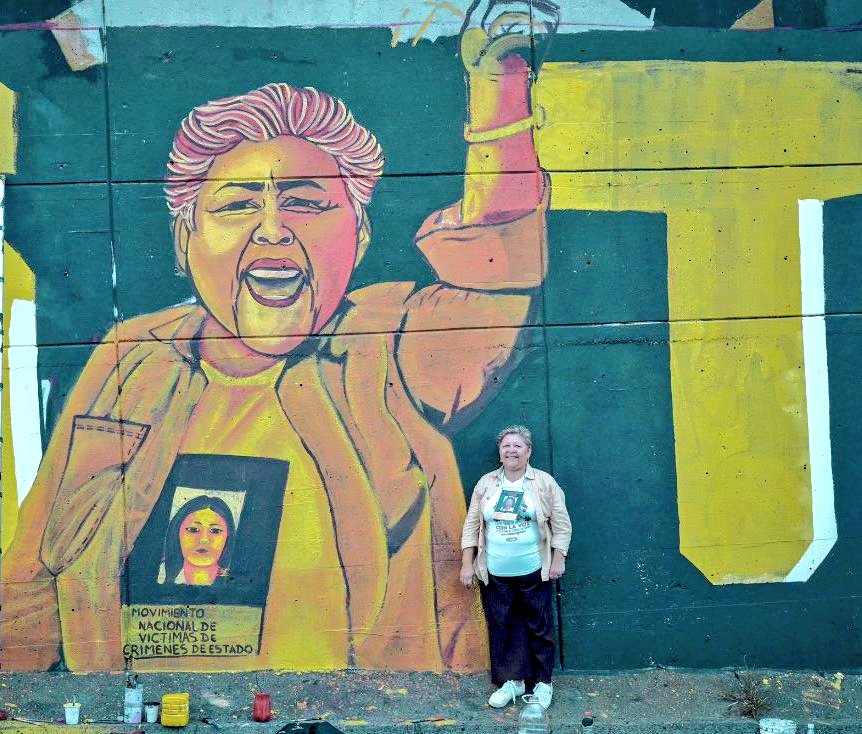

The discovery of the remains has reignited deep-seated emotions in the city, with families and activists long accusing officials of stonewalling a search of La Escombrera in an attempt to cover up crimes committed during the height of paramilitary and state-sponsored violence in the nearby Comuna 13 neighborhood in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Earlier in January, Medellín’s Mayor’s Office reportedly erased a graffiti mural exalting the mothers of the city’s disappeared, and a journalist at a local radio station even went as far as to accuse the mothers of burying their own children in the dump – sparking outrage from citizens.

As we approach a potential inflection point in the history of La Escombrera, let’s take a look at the site’s history and significance to the city of Medellín, and to Colombia’s wider armed conflict.

The history of the Comuna 13

The history of La Escombrera is inextricably linked to Medellín’s embattled Comuna 13 district, which is now a hotbed for tourism in the city.

Also known as San Javier, the Comuna 13 is one of 16 districts, or “comunas,” that make up the city. Located in the western mountains, it was first heavily populated by internally displaced people from Colombia’s decades-long armed conflict, and became known as an “invasion neighborhood,” since its population boom in 1994, according to Medellín’s Mayor’s Office.

Its geographic location as a transit point to the Gulf of Urabá on Colombia’s Caribbean coast makes it strategic for drugs and weapons trafficking, noted researcher Adriana González Gil, and has prompted violent clashes between Colombia’s leftist guerrilla groups, right-wing paramilitaries, drug trafficking organizations and state security forces.

A report by Colombia’s National Center for Historical Memory found that this constant struggle led to lacking state presence. From the mid-1990s, leftist urban militias, including the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), and the now-defunct Armed Commandos of the People (CAP) exerted control on the population in the absence of the state. Until the 2002 Orión military operation, these groups became the de facto authority in much of the comuna, subordinating the population and using the area as a refuge for illicit activities.

Operation Orión

In an attempt to eradicate leftist militias, the Colombian military planned an armed operation within the district. Orión, the largest urban military operation in the country’s armed conflict, began on October 16, 2002, with the backing of Medellin’s Mayor’s Office and the government of newly-elected President Álvaro Uribe Vélez.

The months-long siege became emblematic for abuse in the context of Colombia’s armed conflict, with the military using excessive violence, arbitrary detentions and forced disappearances on members and suspected members of the militias. It would also be revealed that the Cacique Nutibara bloc of the right-wing United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) – which had by this time been designated a terrorist organization by the United States – aided the military in their offensive.

In 2008, Diego Fernando “Don Berna” Murillo, a former Medellín Cartel associate and then-commander of the Cacique Nutibara bloc, testified about the paramilitaries’ involvement in the operation. “Cacique Nutibara carried out intelligence, managed to locate guerrillas, and infiltrated the civilian population. This information was later sent to the military forces,” he stated at the time.

Official data recorded by the Colombian Popular Research and Education Center details 150 government-led raids, the arrests of 355 people – 82 of which were formally charged with crimes – one civilian death, 38 civilians wounded, and eight disappearances. Other sources, however, estimate higher human costs of the operation. As per the Corporación Jurídica Libertad human rights NGO, Orión led to 80 wounded civilians, 17 homicides committed by state forces, 71 assassinations by paramilitaries, 12 victims of torture, 370 arbitrary detentions, and six forced disappearances during the operation, a number that rose to over 100 in the subsequent months.

Although the operation was labeled by President Uribe and then Medellín Mayor Luis Pérez as a success for removing the militias, the Comuna 13 was effectively left under the control of the brutal paramilitary bloc until the AUC’s demobilization in 2003, and the Comuna – and much of the city – still struggles with an organized crime problem to this day.

In the years following the assault, President Uribe has defended the operation and denied the involvement of paramilitaries, despite evidence to the contrary, and recently claimed the bodies in the dump were put there by leftist guerrillas.

“The community itself is a witness to the bodies that were thrown by terrorist organizations into the Escombrera since 1978. Even in 2019, the community asked for the dump to be closed because they kept throwing bodies there,” Uribe recently posted on X. “The [Comuna] 13 is an important touristic destination today, receiving over a million visitors every year. What was an epicenter of crime, is now a center of art and culture,” the former president added.

In recent years, the city has attempted to revitalize the embattled district, including investments in transportation and tourism in an effort to connect it to the rest of the city. It is now a destination for foreign and domestic tourists to visit outdoor art exhibits, outdoor escalators, its metrocable system, and other attractions. But even as Medellín’s violent crime rate has dropped, the Comuna 13 remains one of the most affected districts in terms of violence, according to the Ombudsman’s Office.

A continued silencing of victims in the Comuna 13

The recent finding of human remains in La Escombrera has reignited tense relations between victims of Colombia’s armed conflict and a sector of the political establishment that benefited from the victimization of populations in the past.

As news emerged of the discovery, families with missing relatives spoke out about previous attempts to silence them. “We were not crazy women or guerrilla members,” Luz Elena Galeano, a resident of the Comuna 13 who has been searching for her missing husband for 16 years, told newspaper El Espectador.

A collective of mothers searching for family members from the Comuna 13 also issued a statement in El Espectador saying they were victims of “violent and revictimizing practices” by state institutions.

“We were told we were crazy, so now, the country and the world can see how that same madness overcame what administrations, institutions, and public officials dared to deny,” the statement read.

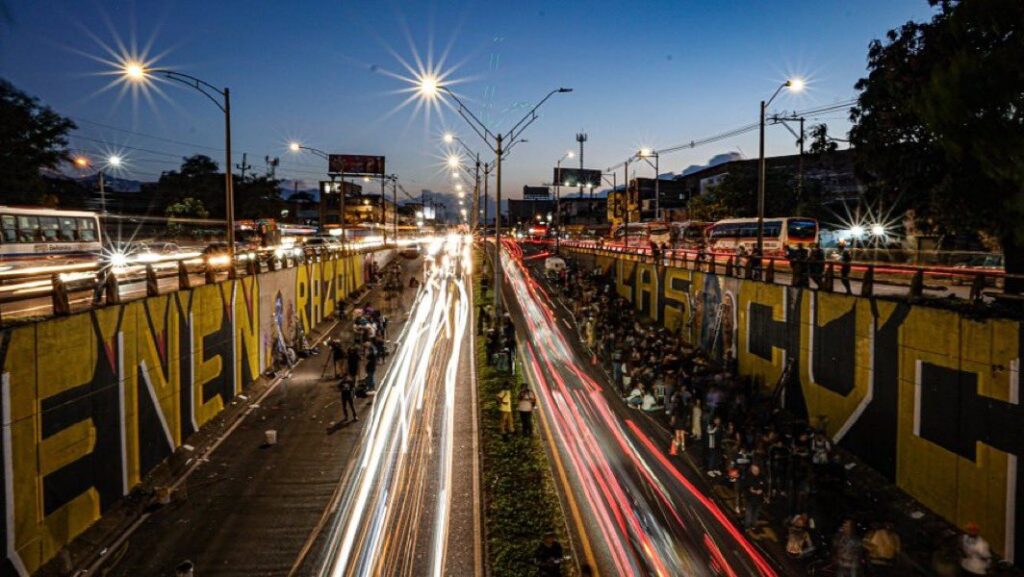

A mural from local graffiti artists which read “The mothers are right” exalted the searching mothers and alluded to Uribe’s involvement in the disappearances in the Comuna 13 was recently erased by the Mayor’s Office. Mayor Federico Gutiérrez claimed, “graffiti as artistic expression is one thing, as we’ve achieved in the Comuna 13 … Another very different thing is disorder and those who want to instill chaos and make our city ugly.”

Others have taken the rhetoric even further, suggesting that family members may have dumped bodies of their loved ones in La Escombrera. In a recent interview with a member of the graffiti collective, Néstor Morales, the brother-in-law of Uribe ally and former President Iván Duque and the news director of Blu Radio, asked his guest, “Could you swear, assure me, that those people found in La Escombrera were not buried there by their relatives?”

Stunned, the radio guest replied, “How is it that you are telling me that possibly a relative went and took the remains of their children and buried them somewhere in the city?”