Even before taking office, Guatemala’s President Bernardo Arévalo had become a systematic target of the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP), led by Consuelo Porras, the attorney general whom the United States government has labeled an antidemocratic and corrupt actor.

Over the course of at least 12 judicial actions against the ruling party, the prosecution has carried out what many analysts describe as a “political offensive”, and what some openly call an attempted “coup”, setting the stage for a struggle over control of Guatemala’s justice system and public institutions heading into 2026.

On the night of October 26, Arévalo denounced that the Prosecutor’s Office and members of the Guatemalan justice system were attempting to overthrow his government by fabricating criminal cases against him and prosecuting Indigenous leaders who took to the streets and highways to defend the results of the June 2023 presidential elections. Since those historic elections, the MP under Porras (2022–2026) has repeatedly tried to remove Arévalo from office. He was sworn in on January 14, 2024, after months of uncertainty and politically driven legal persecution from sectors of the justice system.

Arévalo accused Porras of trying to sink the country and called out Judge Fredy Orellana, her close ally, for endorsing judicial proceedings against innocent people. “They want to drag Guatemala down. This judicial onslaught, built on illegal actions, shows the same intent as before: to derail the rescue of democratic institutions and to create conditions to corrupt the selection processes for justice-sector authorities and the 2026 appointments,” Arévalo stated.

His comments came on the heels of one of the first major security crises of his administration, after members of the Barrio 18 gang escaped from the Fraijanes II prison on October 29. Porras seized on the crisis to request impeachment proceedings against Arévalo and Vice President Karin Herrera for alleged failure to perform their duties.

But the prison escape is only one of the many fronts opened against Arévalo’s administration; several of the ongoing cases aim directly at undermining the legitimacy of the 2023 election results, when the Movimiento Semilla party emerged as a political force. According to analysts consulted for this story, these actions are not merely attempts to criminalize the ruling party, but also efforts to weaken its institutional capacity ahead of the high-stakes appointments scheduled for 2026.

The lawyer and president of Acción Ciudadana, Manfredo Marroquín, reiterated that: “Elections to renew authorities of justice institutions (Attorney General’s Office, Supreme Electoral Tribunal) are scheduled for 2026, and whether the threat of a coup d’état remains will depend on the final composition of all these institutions.”

A sustained offensive from the Prosecutor’s Office

News outlets report that the Public Prosecutor’s Office had launched roughly 12 judicial and political actions intended to block Arévalo’s arrival to power, restrict his ability to govern, or undermine the legitimacy of his presidency. The offensive began in 2023 with the “Semilla Corruption” case, opened by the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity (FECI), following allegations of forged signatures during the political party’s registration process. This led to raids on the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), the seizure of electoral records, and a request to dissolve the party.

In 2024 and 2025, FECI opened new fronts: it pressed charges against former TSE officials, including the ex-director of its IT department, and advanced theories questioning the election results, feeding narratives of fraud. Judge Fredy Orellana, who was sanctioned by the U.S. in 2023, issued rulings to suspend Movimiento Semilla, order arrests, and pursue actions to invalidate the party altogether. Among the dozen cases are prosecutions of Indigenous leaders who defended the election results through peaceful protests, as well as actions targeting community authorities who supported the democratic transition.

By late 2025, the MP had used the Barrio 18 prison break as grounds for a new impeachment request against Arévalo and Herrera, accusing them of dereliction of duty. At the same time, the Prosecutor’s Office opened investigations into the current administration’s security officials, building a narrative of negligence aimed at directly implicating the president. The MP also issued arrest warrants, carried out raids, and demanded information from executive agencies — tactics widely seen as attempts to paralyze the government.

Taken together, these 12 actions — such as impeachment requests, criminal complaints, raids, seizure of electoral documents, charges against social leaders, the criminalization of protesters, and attacks on the Semilla party — constitute what constitutional lawyers describe as a “judicial offensive.”

According to constitutional lawyer Edgar Ortiz Romero, these attacks do not represent a conflict between the entire judiciary and the president, but rather between Arévalo and a group of co-opted judges operating within the system to undermine his mandate. If it is not a coup, he told Latin America Reports, “You could call it something else, but the objective is the same: to erase the political party that won.”

Structural roots: the shadow of the CICIG

To understand the magnitude of the current dispute, one must look beyond the newest legal cases. Experts argue that the roots of the conflict lie in the investigations led by the now-defunct International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), an international body tasked with investigating crime and human rights abuses in Guatemala that was terminated in 2019 by then-President Jimmy Morales.

Arévalo and his allies have long supported institutional reforms aligned with the work that CICIG once advanced. According to constitutional lawyers consulted for this story, the MP’s current offensive is a backlash from the powerful groups investigated by CICIG during the administrations of Morales and Alejandro Giammattei. These actors are now seeking to reassert their influence in the courts, not only by targeting Arévalo but by blocking his efforts to institutionalize deeper reforms.

While the MP remains active in its pursuit of cases against the Arévalo administration, it has allowed numerous corruption complaints involving previous governments to languish. Morales’s presidency was marred by the “Hogar Seguro” tragedy, which left 41 girls dead, as well as infrastructure scandals, including the repeatedly collapsing Chimaltenango bypass. CICIG and the MP under Thelma Aldana also uncovered evidence of illicit campaign financing within Morales’s FCN party—yet the case remains unresolved.

Manfredo Marroquín, president of the watchdog organization Acción Ciudadana, emphasized to Latin America Reports that long before Arévalo took office, the Prosecutor’s Office had sought to block his rise to the presidency and to investigate him under allegations of corruption. “This is a political test for a justice system that has been co-opted,” Marroquín said.

“They build hypotheses for cases that don’t exist. It’s a struggle for power in the service of impunity and corruption, led by forces that were investigated by CICIG.” He added that these attempted coups have failed to gain public support: “It’s a very small group within a corruption network embedded in the judiciary, but they still have the power to create confusion.”

The stakes of 2026: what comes next

Arévalo has invoked the Inter-American Democratic Charter of the Organization of American States (OAS) and urged the international community to keep its attention on Guatemala. Experts say this reflects a broader concern that national institutions may not fully safeguard the separation of powers, amid threats of a coup and ahead of crucial second-tier elections.

Next year, Congress must appoint new electoral judges, five full magistrates and five alternates from a shortlist of 20 candidates. The process begins in January 2026, with new authorities taking office on March 20.

Arévalo will also be responsible for selecting the next attorney general and head of the Public Prosecutor’s Office from a shortlist of six nominees, for a four-year term. Other oversight bodies, including the Constitutional Court, the Comptroller General, and the Superintendent of Banks, are also set for reconfiguration in 2026.

For analysts, this makes 2026 a watershed moment during which key segments of the judicial system will be renewed and the balance of power within state institutions will be defined. If the Prosecutor’s Office succeeds in weakening the president now, they warn, corrupt actors including individuals sanctioned by the United States could secure a justice system aligned with their interests and perpetuate impunity. If Arévalo withstands the offensive, Guatemala could see a turning point in the fight to strengthen judicial independence.

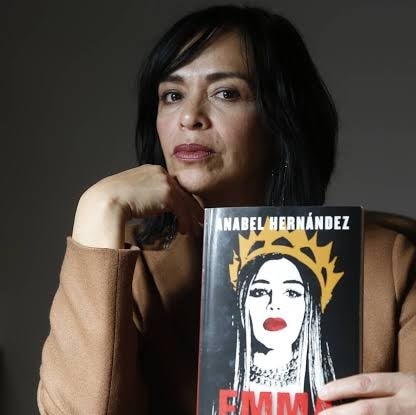

Featured image: Bernardo Arévalo, President of Guatemala via @BArevalodeLeon