The United Nations recognizes the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights. However, weak infrastructure and climate change are challenging Mexico City’s ability to provide clean and adequate water to residents. Mexico City’s water is quite literally disappearing. “I have no doubt that in 2022 there will be a crisis, the reservoirs are completely depleted,” says water expert Rafael Sanchez Bravo.

What is happening?

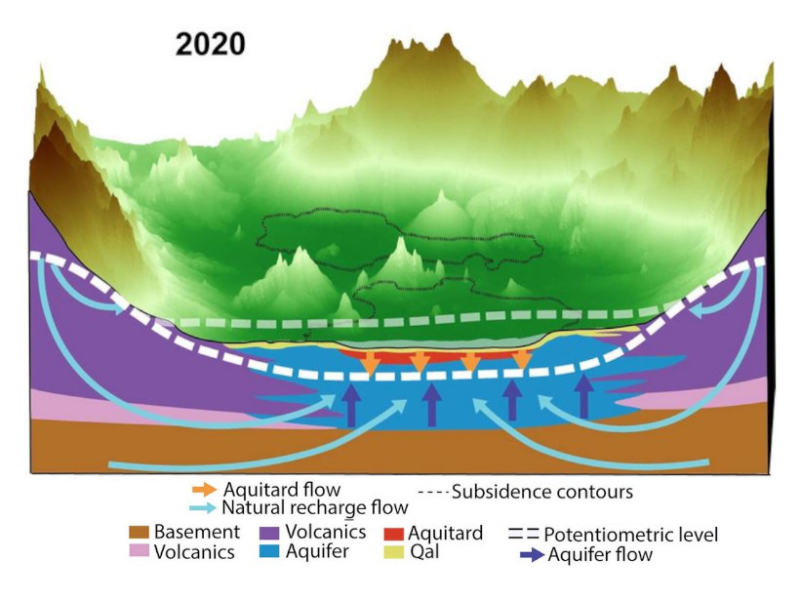

The ancient Aztecs originally engineered the origins of Mexico City on top of Lake Texcoco and left the surrounding natural freshwater lakes intact for use. However, as the city grew the lakes were drained to make way for infrastructure, homes, and a growing population. With expansion came an increasingly dire water security dilemma. Much of the city’s water supply comes from an underground aquifer that is being drained at an irreplaceable rate. As the aquifer is drained, Mexico City is sinking downwards rapidly at twenty inches per year.

Despite heavy flooding and rainfall, the city is facing a water shortage. In fact, more than 20 million residents don’t have enough water to drink for nearly half the year. According to the BBC, one in five people have access to only a few hours of running water from their taps a week and 20% have running water for part of the day. Counting on clean water is far from reliable for many.

Current projections estimate that global demand for fresh water will exceed supply by 40% in 2030. Mexico City, one of the largest cities in the world, has a population of nearly 22 million and is growing steadily with population growth expected to hit 30 million by 2030.

Mexico City is one of 11 cities predicted to reach what is called Day Zero, or the day when the water runs dry. This is nothing short of a crisis. “Each drop of water that passes through the Mexican capital tells a heroic, tragic, unfinished story of urban growth and human development,” writes Jonathan Watts for The Guardian.

Where is the water?

There are a few reasons why a city on top of an aquifer and with a very heavy rainy season struggles to provide potable water for its residents. Specifically, the challenges to water security are widespread and difficult for urban designers, environmentalists, and politicians alike.

A lack of sanitary wastewater treatment across the city hinders water collection and poses a huge challenge to keeping existing water clean for use. Additionally, Mexico City’s pipes are old and leaking. According to the University of Pittsburgh, Mexico City loses 1,000 liters of water per second because of an outdated water system that is being crushed by the falling city and punctuated by thousands of small leaks. Finally, rainwater collection exists, but no city-wide system is in place. When it rains, water often mixes with sewage and cannot be used.

Why is the city sinking?

Mexico City ended all groundwater drilling in the city central in the 1950s yet water is pumped up from below in the surrounding areas and GPS data has found the city is continuing to drop. As water extraction has chased groundwater deeper and deeper underground, the clay lake bed is now completely dry and the tightly packed mineral soil is causing irreversible compaction. This phenomenon, called subsistence, does not have a quick fix.

Additionally, water from rain storms cannot permeate the concrete-covered city and refill the aquifer. A 2021 study made the claim that there is no hope for significant elevation and storage capacity recovery. Much of the water must be pumped to the city using hydro engineering from reservoirs thousands of kilometers away.

Climate change is a threat multiplier

Mexico continues to experience one of the most widespread droughts in decades. Unusually low rainfall has already reduced access to water in the capital. The reservoirs in Cutzamala outside the city provide a quarter of the city’s water but in 2020 the reservoirs were nearly 18 percentage points below normal levels. As precious reservoir levels plummet, the city authorities have reduced the flow from the reservoirs, which has been affecting tap water access. Some residents are relying on water delivery trucks and even donkeys.

This occurrence is predicted to repeat. “Climate change has definitely changed rainfall patterns,” Rafael Carmona Paredes, director of the Water System of Mexico City (SACMEX) told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. “We have to prepare ourselves in lots of ways to be able to cope with these variations in climate conditions.” Researchers have estimated the availability of natural water for the city could decrease by up to 17% by 2050 as temperatures rise.

“More heat and drought mean more evaporation and yet more demand for water, adding pressure to tap distant reservoirs at staggering costs or further drain underground aquifers and hasten the city’s collapse,” writes Michael Kimmelman for the New York Times.

Researchers have pointed out potential future issues facing water supply. Global warming could exacerbate the water crisis in Mexico City with less rainfall, algae blooms in warm reservoirs, and increased demand for water as a result of a warming planet.

What has been done?

Mexico recognizes the pressing issue of water facing their biggest city. Mexico City initiated the Green Plan project, which will run until 2022 with goals such as reducing groundwater losses and repairing water infrastructure among others.

Former president Enrique Peña Nieto signed a series of presidential decrees in 2018 to create water reserves in nearly 300 river basins throughout the country. And $7.4 billion has been dedicated to mitigating the water crisis by Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo in 2019.

An expert offers a solution

While current state and local decrees are a big step towards a necessary goal, according to Harvard-educated, Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) expert and architect Loreta Castro Reguera, the most effective approach is a decentralized one and sustainable as well as accessible to communities city-wide.

WSUD is an emerging approach to urban development aimed at minimizing the hydrological impacts of urban development on the environment. Latin America Reports spoke to Requera about her Mexico-city based team and their mission of designing the city through infrastructural public spaces that promote access for impacted communities and understanding different strategies for managing water.

“It’s a paradox. It’s a catastrophe. Right now we have a city that is sinking and our infrastructure is literally breaking. And on the other hand we have no way for the water to filter [into the aquifer] naturally,” says Reguera. “And you can imagine how expensive it is to change the entire piping system.”

Her projects demonstrate that public spaces can serve simultaneously as parallel water management infrastructures. Reguera and her partner Jose have coined the term “retroactive infrastructure.” This refers to non-traditional infrastructure that can solve rather than exacerbate the water issues. Some projects include water filtration systems and utilizing open spaces to catch and save rainwater in larger tanks than would fit in a building. “We want these spaces to become decentralized infrastructure,” she says.

“For example, we completely transformed the landscape of a park in a very poor community. It was on a hillside and instead of just a slope we terraced the slope and filled the terraces with local volcanic gravel, which is highly permeable. We created filtration terraces and made it a sponge to catch rainwater and filter it into the aquifer. We removed the fences, opened the entrances, and kept all the trees.”

“It is not like we will solve the water crisis with rainwater collection but it could help a lot if we start making reservoirs all around the city,” she says. “So the question is how we can start transforming these reservoirs into open and public spaces. They can provide enough water for the entire city.”

Reguera is hopeful. The city has been active in creating wetland systems to treat wastewater that will eventually become a source of water for the surrounding areas. “It is really great to see how the city is making an effort,” she says. “They are experimenting to see how much open spaces can work. It is something that only started three or four years ago so we won’t see a transformation immediately. But there is a lot of consciousness right now.”

Reguera describes the work of parallel infrastructure as “stitching together the city with open spaces.” There is no easy solution to Mexico City’s water crisis, but perhaps it lies in communal, accessible spaces above ground instead of below.