On Tuesday, Hurricane Iota became the second Category 4 hurricane to devastate Central America and the Caribbean in as many weeks, following in the path of Eta, which left at least 150 people dead. Hitting just a few miles from where its predecessor made impact, the Nicaraguan city of Puerto Cabezas has seen heavy structural damage and been left without power.

Not only is Iota believed to be the strongest hurricane this late in the season, but this also marks the first time on record that two major storms have been produced in the Atlantic in November.

These back-to-back strong storms coming so late in the season is not just an ominous sign of things to come as water levels continue to warm, it’s a reminder that Latin America is already living with the dire consequences of climate change.

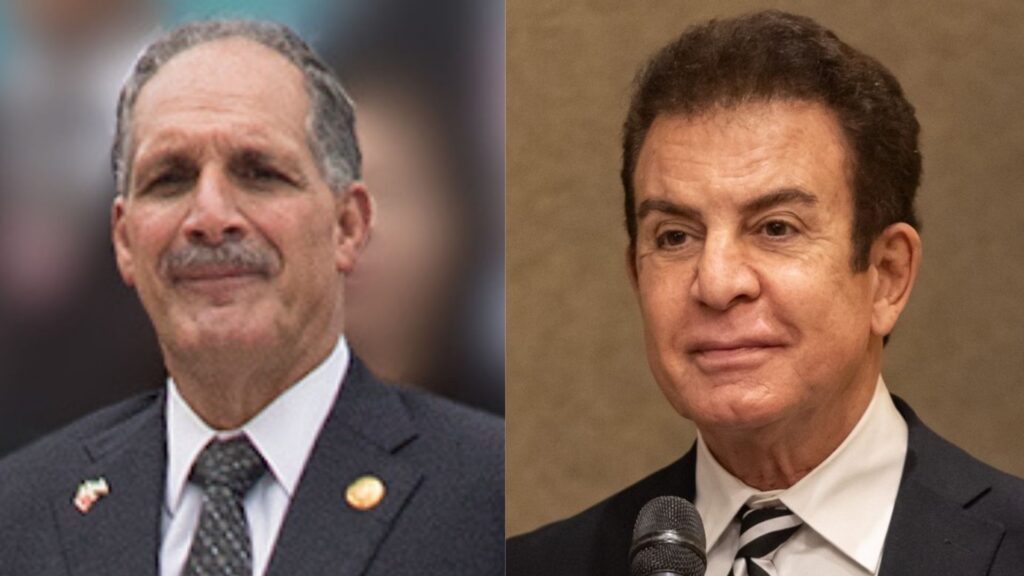

“Every time there’s a natural disaster as a result of climate change, we acquire debt,” Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei said Monday. “And we have come out to knock on the doors of the generous, banks and multilateral organizations, that give us higher financing to achieve a reconstruction. This has brought a vicious cycle, where we get into debt, we reconstruct, it gets destroyed, we get into debt, we rebuild, and it gets destroyed again.”

Earlier this week as it worked its way temporarily to a Category 5, Hurricane Iota flooded the Colombian port city of Cartagena and brought heavy damage to Colombia’s Caribbean islands of San Andres and Providencia, where at least one person was reported killed.

More than 3.6 million people in Central America – mostly Honduras – were already affected by Hurricane Eta to some degree, the Red Cross reported this week.

This year has seen the most amount of hurricanes swell up in the Atlantic Ocean since record-keeping started in the 1850s, according to the United States Office of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In addition to the economic fallout that comes from this uptick in natural disasters, the region has already seen climate migration firsthand.

In 2017, Hurricane María killed at least 2,975 Puerto Ricans and led an estimated 150,000 people to leave the island.

The World Bank estimates that over the next 30 years, 17 million people across all of Latin America could become climate refugees forced to leave their homes.

People also flee from places where their crops have been destroyed and whole industries have been taken away from them, especially agricultural ones like fishing and farming. In Puerto Rico, coffee production remains a fraction of what it once was. In Guatemala, for example, people are migrating north because of crop shortages due to extreme cycles of droughts and flooding in the areas of the country where the effects of climate change have been most pronounced.

“It’s fewer days of rainfall but more intense rainfall, sometimes harmful because it’s so strong,” Alex Guerra Noriega, general director of the Climate Change Research Institute in Guatemala, told NBC News last year. “And then you get a few weeks with no rainfall and then you have these drought conditions and your crop fails.”

After this past decade that scientists say has been the warmest the Atlantic Ocean has experienced in at least 3,000 years, stronger hurricanes and longer hurricane seasons are inevitable. When coupled with the droughts and flooding that have already wrecked the region, it makes it hard to find solutions going forward.

“I don’t see a lot of options for Central America to deal with the global warming issue,” meteorologist Jeff Masters told The Guardian. “There are going to be a lot migrants and, in fact, a lot of the migration that’s already happening in recent years is due to the drought that started affecting Central America back in 2015.”