Caracas, Venezuela – Since the start of the presidential campaign on July 4, many media and fact-checking websites have been blocked on all major internet providers in Venezuela.

On July 22, less than a week before the July 28 election, a new wave of blocks came into effect bringing the total number of blocked media and NGO websites to 12 during this election cycle.

Media blackouts aren’t unheard of in Venezuela. According to a report by the NGO Espacio Público, in the 20 years of the ruling party of Hugo Chavez and Nicolás Maduro, over 400 media outlets have disappeared, including radio stations, print outlets, television channels and digital platforms.

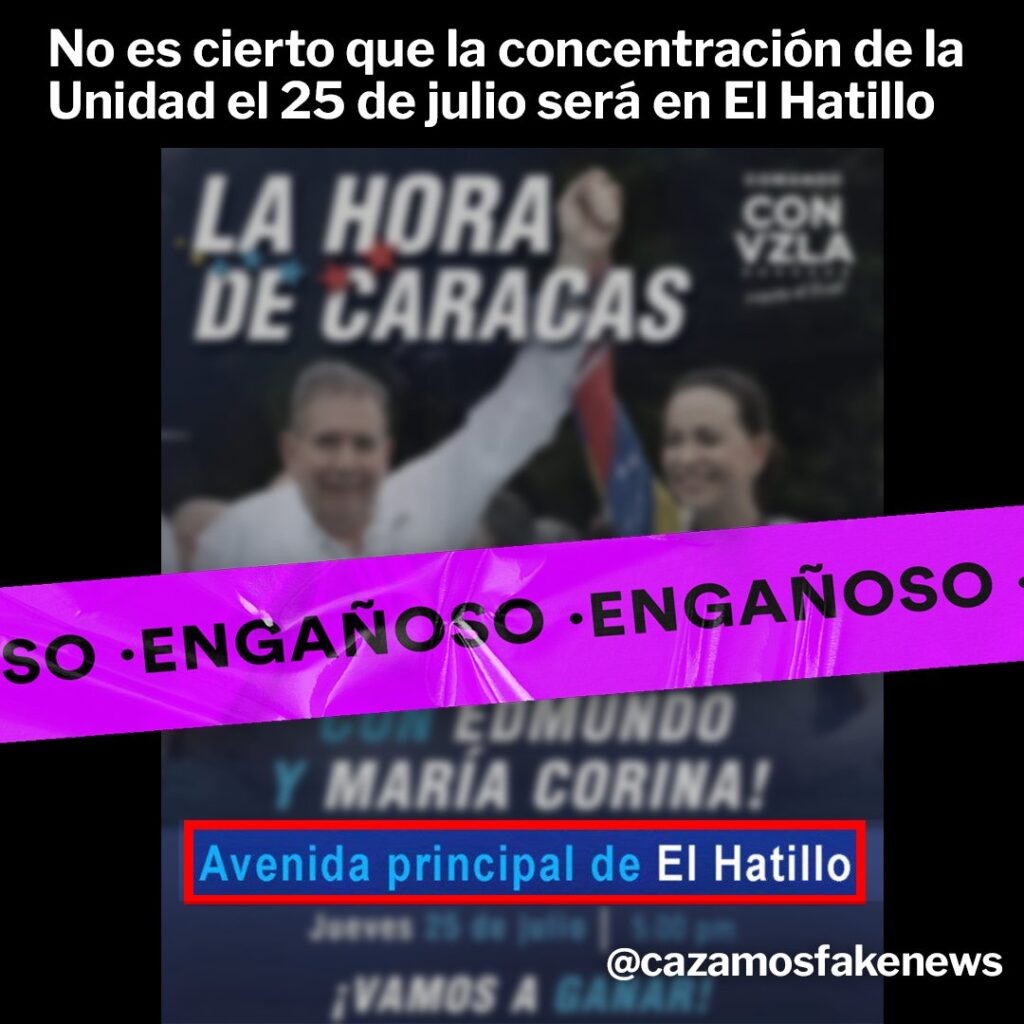

The dwindling of available, trusted news sources in Venezuela is coupled with a wave of digital rumours and disinformation during this election cycle. “We had not seen so much misinformation and diversity of techniques to misinform as we are seeing right now,” said Adrián González, director of Cazadores de Fake News (Fake News Hunters), last week on the program CocuyoClaroyRaspao.

Given their increasingly limited reach, media outlets and fact-checking agencies have turned to artificial intelligence (AI) as a tool to keep citizens informed ahead of elections.

Chatbots that help detect fake news

Efecto Cocuyo, an independent Venezuelan digital news outlet, launched an AI chatbot on WhatsApp called “La Tía del WhatsApp” (The Aunt of WhatsApp). The chatbot is the first of its kind to be created by Venezuelan media and was launched on June 9.

The launch of “La Tia” was closely followed by a similar model from Cazadores de Fake News, a fact-checking website which was also recently blocked. Both chatbots use international numbers as a security measure against censorship and data protection.

Intended as a direct antidote for disinformation and censorship, users can send photos, videos, WhatsApp text chains, or any other content disseminated on the internet to be verified by the chatbot. If the submitted content has already been fact-checked by Cocuyo Chequea – the fact-checking division of Efecto Cocuyo – the chatbot will immediately respond with the verified information.

The coordinator of the project, Jeanfreddy Gutiérrez Torres, told Latin America Reports how their chatbot “does not process language,” instead “it is programmed to recognize the type of content submitted by the user.” This has caused some confusion from users, who expect the chatbot to function like other generative AI models like ChatGPT which use large language models (LLMs).

While the artificial intelligence lacks the ability to converse with users, the character of “La Tía” is brought to life by the voice of Venezuelan stand-up comedian Ana Luisa Ces. She voices the introductory video that explains how the chatbot works as well as a summary of fake news stories that have been disproved by the team, which is sent out by the chatbot every week.

The chatbot is constantly monitored by journalists. Aptly called “sobrinos” (cousins), they respond directly to users when the chatbot troubleshoots or does not arrive at the user’s desired response.

La Tia’s algorithm is very skilled at “recognizing recurrences,” meaning that it is able to match content with the same hoax in a slightly different presentation. For example, if a new meme is similar to something previously fact-checked by the database, the programme is able to recognise new iterations of the same story and inform users immediately, simultaneously learning from the new input and adding to its database.

This AI chatbot model has been very important for Cocuyo Chequea, as it has brought fact-checkers closer to where disinformation circulates.

Gutiérrez, who is a data-driven journalist and fact checker, said that “people consume disinformation when it is successful, which tends to originate from audio messages and memes that go viral.” Despite having tools to detect what is circulating on social media, on instant messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, fact-checkers are practically “blind, [they] have to rely on [their] audiences,” Gutiérrez explained.

The chatbot has become “a great ear” for fact-checkers to detect disinformation at the source and serve their audiences directly. According to Gutiérrez, close to 80% of the content that Cocuyo Chequea verifies now comes directly from the chatbot.

While this model is still in its early stages, it has proven how AI has begun to be extremely useful in the fight against disinformation and censorship in the election campaign. It brings media outlets closer to its audiences and its simple use as it does not require the need for VPNs to circumvent website blocks.

As the parameters for free press in Venezuela continue to be restricted, independent media outlets will continue to adopt new technologies to keep informing.