El Cocuy National Natural Park, Colombia — “We have to walk a bit further each time we come up here,” says Wilson Blanco, leading us over Colombia’s icy roof.

That’s the gag among the El Cocuy mountain guides: as the glaciers recede, they must hike further up the mountain to reach the ice that marks the trek’s highest point.

Except it’s no joke.

The receding icefield, at 4,850 metres (15,900 feet), reveals a grey moonscape of boulder-strewn moraine fields and tilted slabs of sandstone. It’s a stark reminder of how global warming is melting Colombia’s glaciers.

“We can’t imagine the mountains without the glaciers. For us it’s like the end of existence,” says Wilson. He is U’wa, one of an indigenous community that has lived in the cool shadows of El Cocuy for millennia, the traditional guardians of the mountain ranges.

The glaciers are sacred for U’wa and play a vital role in the spiritual harmony of the mountain range, as well as providing a constant stream of meltwater to the meadows below.

Except now, watching the sun filter through the blue ice that forms the wall of the glacier above us, and water puddling on the hot rocks below, there’s a sobering realization: these glaciers are going down the plughole.

A grand arena

This has already happened in nearby Venezuela – it’s only 50 kilometers away as the condor flies – which last year became the first Andean country to lose its last ice field, the Humboldt Glacier.

In Colombia, the El Cocuy glacier has shrunk by 38 per cent in the past 34 years, according to a recent geological study, and at the current rate of loss, the ice covering is expected to totally disappear by 2048.

The glaciers’ retreat, notes the Brazilian-Colombian scientific team behind the survey, is down to “factors related to global warming, such as the increase in mean annual temperature and the decrease in precipitation rates.”

With good reason, the hiking trail is named El Sendero del Cambio Climatico, the Climate Change Trail, according to a wooden sign that also reminds trekkers: “the future of mountain ecosystems is in our hands.”

In this grand arena, though, it’s hard to feel anything but very small and insignificant against the magnificent backdrop of cliffs, peaks and forests of frailejones, tall waxy plants that could have escaped from Star Trek’s props department.

For the U’wa, though, visitors to the mountain are an embodiment of wider planetary ills.

“We see the glaciers disappearing and blame the tourists who come and leave rubbish,” says Wilson, as we puff up the hill, our hiking poles clattering in the rocks.

“So yes, sometimes we want to keep away the outside world, and those that create problems for mother earth.”

Look, but don’t touch

These sentiments have led sectors of the U’wa community to push back against tourism in El Cocuy.

Like in 2017 when the mountain range was locked off after protests following an incident the year before when some fundraising footballers had a kick-around on one of the glaciers, filming it and posting it on Youtube.

The footage sparked fury among the local communities who blockaded the El Cocuy national park while compromises were hammered out between interest groups.

The mountain did reopen in 2019, with severe restrictions.

Gone was the spectacular five-day hiking circuit – rated among the top ten high-altitude treks in the world – to be replaced with three one-day treks to reach just below the glaciers.

Another rule was that visitors should avoid touching the ice field which for U’wa was a spiritual sanctuary, indigenous leader Danilo Tamarán explained to La Raya magazine last year.

Local guides from local communities knew how to respect the mountain, he said. But outside tour agencies were increasingly coming in and breaking the rules.

He likened this to “trampling on a sacred church” and proposed periodic closures of the park to allow for a “spiritual healing”, ward off bad energies and restore natural balance.

A line in the ice

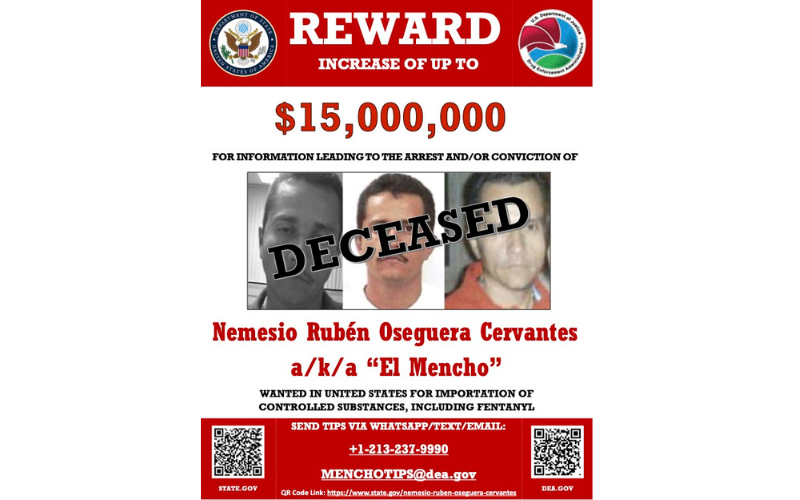

His doubts are well founded. As recently as January this year, a video was circulating showing Bulgarian mountaineers roping up to ascend the glacier while Colombian hikers plead with them to stay off the ice.

“I’ve spent a lot of money and time to come here, so why not?” retorts the foreign climber as he connects his line to friends already scaling the slope behind.

These infractions risk upsetting the U’was but also infuriate local tour companies whose livelihoods depend on visitors in this impoverished corner of Colombia.

The national park receives around 2,000 visitors per month, with each paying around US$40 in entrance fees, guides and transport per day, not to mention paying for hotels and restaurants. Any park closures have a devastating impact on the local economy.

Each group of four hikers must hire a mountain guide, drawn from hardy campesinos that farm the land skirting the national park and have spent their lives walking the high trails.

On any given day, hikers and guides set off in the freezing predawn from the three start points to the glaciers of Rita Cuba Blanca, Concavo or the aptly named Pulpito del Diablo, a towering sandstone outcrop that is El Cocuy’s most emblematic feature.

Their own terms

All three trails start at around 3,900 meters (12,800 feet) and climb to just under 4,900 metres (16,000 feet), steeply climbing then descending over the same route over eight hours.

It’s essential to acclimatise to the altitude, and for many hikers this means spending two nights at one of the bunkhouses high on the mountain.

Guicany Farm is one such site, run by Juan Carlos Carreño, a campesino whose family has farmed a high section of the mountain for generations and is now rewilding land on the edge of the national park.

Like most tour operators he is constantly checking the political temperature of the mountain and is alert to threats of closure. For now, though, “it’s pretty stable now with a steady flow of visitors,” he says.

Carreño is close to the U’wa community and has connected us to our U’wa guide, Wilson. It’s a mistake to see the U’wa as opposing tourism, he says, they just want it done on their terms.

“U’wa now see climate change as inevitable and have a broader picture of its causes, not just caused by visitors touching the glacier, though it has always been something sacred to them and should be respected.”

The indigenous will have a bigger say in El Cocuy following a landmark decision won by the U’wa at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in December last year. The ruling allowed for the U’wa’s collective rights to their ancestral territory, and to co-administer Mount Zizimu, which is their name for El Cocuy.

The historic ruling ends a 25-year legal battle and sets a similar precedent for indigenous peoples in Colombia and across Latin America. El Cocuy will be a test case for the new policies that promise to put indigenous communities front and center for ecotourism on their own lands.

“It’s early days yet, but it can only be a good thing,” says Carreño. “Before the U’wa were on the sidelines. Now they will have more say in tourism projects and more income for their communities,” he says.

And more U’wa like Wilson are more likely to get involved in tourism and train as guides: “They are the traditional guardians of the mountains, who better to take people up there?”

Flash and fizzle

Wilson, it turns out, is perfect company for the trek, relentlessly cheerful while setting a steady pace over the paths.

His insights into U’wa life are tempered by practical advice for high altitude trekking. We’ve set off from 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) so are breathless from the first step.

“It’s best to go slow and steady rather than rush,” he says. “And don’t stop every five minutes but take a good break every hour.”

It seems to work. At first we are overtaken by fast-paced hikers – I call them the “flash and fizzle” groups – but soon they are sitting panting and whey-faced by the trail as we plod past. Eventually we are the lead group on the mountain.

Our banter over eight hours of trekking covers food, cars, bikes, music, beers and what snacks are best for a high mountain trek.

On this last point we disagree. I’ve carried a large quantity of sweets and some fizzy drinks to get much-needed sugar quickly into the bloodstream. Wilson has packed hunks of boiled chicken which he swears is the only necessary accompaniment for ascending 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) in four hours, then back again.

“This is pure protein energy,” he says, gnawing on a stringy piece of meat.

“You’ll use up more calories chewing that old hen than you’ll ever get back,” I reply.

Clear lesson

Conversation dwindles on the next section of the hike, a lung-busting scramble up 400 metres of cliff. We pack away our trekking poles as here it’s hands as well as feet needed to clamber over huge boulders.

“This is where many people turn back if they’re not used to the altitude,” says Wilson. Indeed, we’ve passed several other hiking groups along the way with some pale looking participants.

At the top of the cliff we emerge onto the rocky crown of the mountain, and the clearest evidence yet of the disappearing ice.

In the distant rises the Pulpito del Diablo, the Devil’s Pulpit, a sheer rock tower, 80 meters tall, sticking out of a thin skirt of ice.

“Check this out,” says one of our trekking companions. He shows us a picture on his phone taken at the same spot by pioneer climbers in 1938, showing them sitting on a thick glacier.

Now, though, we are perched on bare rock with an hour’s hike ahead to reach the ice line.

That’s the clear lesson from El Cocuy’s Climate Change Trail. The irony is it may be too late.

Editor’s note: March 21 has been declared World Day for Glaciers by the United Nations, to encourage preservation of the vital role of glaciers in sustaining life on Earth for generations to come.

Featured image: Hiking over exposed rock to El Pulpito del Diablo, Devil’s Pupit, a sandstone tower that forms the apex of one of the three El Cocuy treks. Image credit: Steve Hide.