Mexico City, Mexico — The night of December 15, just as Mexico’s most violent year for journalists was coming to an end, influential television news anchor Ciro Gómez Leyva was shot at, just blocks from his home in Mexico City.

Unlike 17 journalists killed that year, Gómez Leyva survived the attack, thanks to the armored vehicle he was driving provided by his news agency, Grupo Imagen.

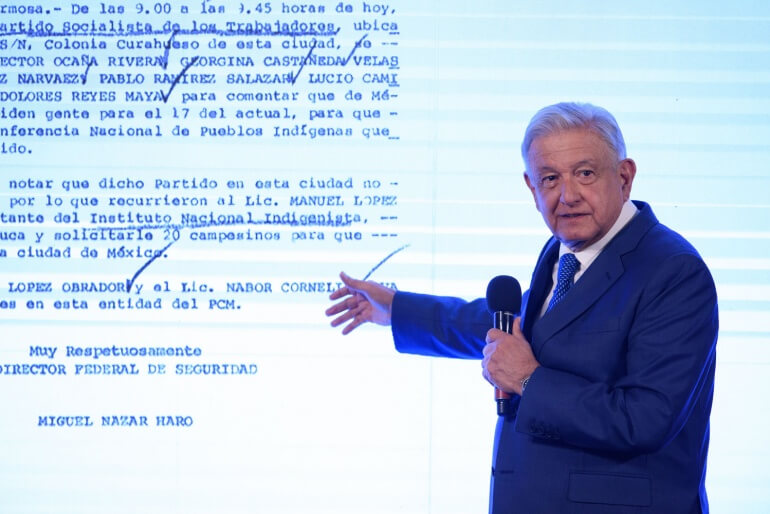

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador immediately condemned the failed assassination attempt against one of his fiercest critics and called for a thorough investigation to find those responsible.

By January 12, authorities reported that all 12 suspects behind Gómez Leyva’s assassination attempt had been apprehended. While Gómez Leyva’s survival is celebrated, and the seemingly efficient, effective response from authorities is commendable, the outcome of his case starkly differs from most Mexican journalists targeted with violence who do not hold the same influence or have access to the same resources as the TV anchor.

“There are two types of Mexicans”

Facing a growing number of threats against them, Armando Linares and Joel Vera, directors of Monitor Michoacán, a seven-person, local, internet news outlet based in western Mexico, first sought protection from the government in late 2021. They decided to seek protection out of fear of retaliation for their investigations into local government corruption in Michoacán.

Security measures such as panic buttons or even personal bodyguards are part of the protocol outlined by authorities to be followed for journalists in danger, measures requested by Vera and Linares which they never received.

Weeks later, on January 31, 2022, three armed men stormed the Monitor Michoacán offices, killing Linares’ and Vera’s colleague, 55-year-old journalist Roberto Toledo.

Shortly after the murder, Linares, his voice cracking in anguish, took to Facebook to condemn his colleague’s murder, promising to deliver justice to Toledo no matter the consequences. He also said his team was aware of who was behind the attack.

“The Attorney General’s Office never issued protective measures for the Monitor Michoacán team which resulted in the two deaths. When there is a threat against journalists, immediate action must be taken, but the prosecutor’s office and mechanisms downplayed the situation,” said Vera.

The violence did not stop with the murder of Toledo, and 45 days later, Linares was shot and killed outside his home on March 15. Monitor Michoacán shut down the publication shortly thereafter.

“I have always said that delayed justice is no justice. It’s impunity,” Monitor Michoacán’s Vera told Aztec Reports days before the one-year anniversary of Toledo’s murder.

To date, authorities haven’t arrested a single suspect in the deaths of the two journalists.

“In the case of Monitor Michoacán, the Mexican government owes a lot because they know who are the perpetrators of the murder of Linares and Toledo,” said Vera.

He also said that by failing to provide sufficient protection to their team after they requested it, and allowing Toledo’s murder to go unpunished, the government’s inaction played a role in the subsequent attack against the Linares.

Contemplating the different outcomes between the attempted assassination of Goméz Leyva and the successful assassinations of his colleagues, Vera said, “It is the same case. There was an attack on the media, and there was an attack on other people, but there were no names, no investigation, and no arrests. I can only explain that in Mexico, there are two types of Mexicans, two types of journalists; those with a high profile and those with a low profile,” he said.

Impunity for acts of violence against Mexico’s journalists

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) 2022 Global Impunity Index, which calculates the number of unsolved journalist murders as a percentage of each country’s population, Mexico is the sixth-worst country when it comes to solving homicides against journalists, behind Iraq, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Syria and Somalia.

In the Western hemisphere, Mexico is the worst-performing country, with 28 unsolved murders of journalists in the past 10 years. Brazil ranked ninth on the CBJ’s annual index.

“Very often these journalists work for smaller local outlets, regional newspapers, regional radio stations or have their own facebook page, and are very active on social media, and you put all of that together and you have journalists who are operating in an extremely violent environment where they are extremely vulnerable to any kind of attack,” Jan-Albert Hootsen, CPJ’s Mexico representative, told Aztec Reports.

The main target of this proliferation of criminal gangs is journalists operating outside of major metropolitan areas (such as Mexico City) and working in small and local news outlets, which are easily identifiable and traceable.

“I think one important detail that we should point out here is that Mexico is pretty much the only country in the world where the number of murders of journalists is steadily rising every year,” said Hootsen.

For the past 30 years, the CPJ has been monitoring the situation in Mexico, and has witnessed the rise in violence against journalists coincide with the general increase in violence in the country following the 2006 declaration of the “War on Drugs.”

“I think it has to do with the fundamental weaknesses of the Mexican state,” said Hootsen.

According to Hootsen, Mexico has pre-existing vulnerabilities that have worsened crimes against media professionals, such as high levels of corruption, underfunded police, and a lack of justice reform.

“They also have to deal with institutions that are supposed to protect them that really don’t,” he said. “Police don’t protect them. They don’t investigate. The prosecution is extremely slow … and even if they do, they tend to only arrest the triggerman, not the actual masterminds behind the attacks.”

“It means that, generally, you can count on a vast majority of cases that anybody who is focused on killing a journalist will have a very good chance of getting away with it,” said Hootsen.

The government only officially recognizes 13 of the 17 murders of Mexican journalists that took place in 2022. Of those cases, authorities have convicted only five men for their participation in the murder of journalists.