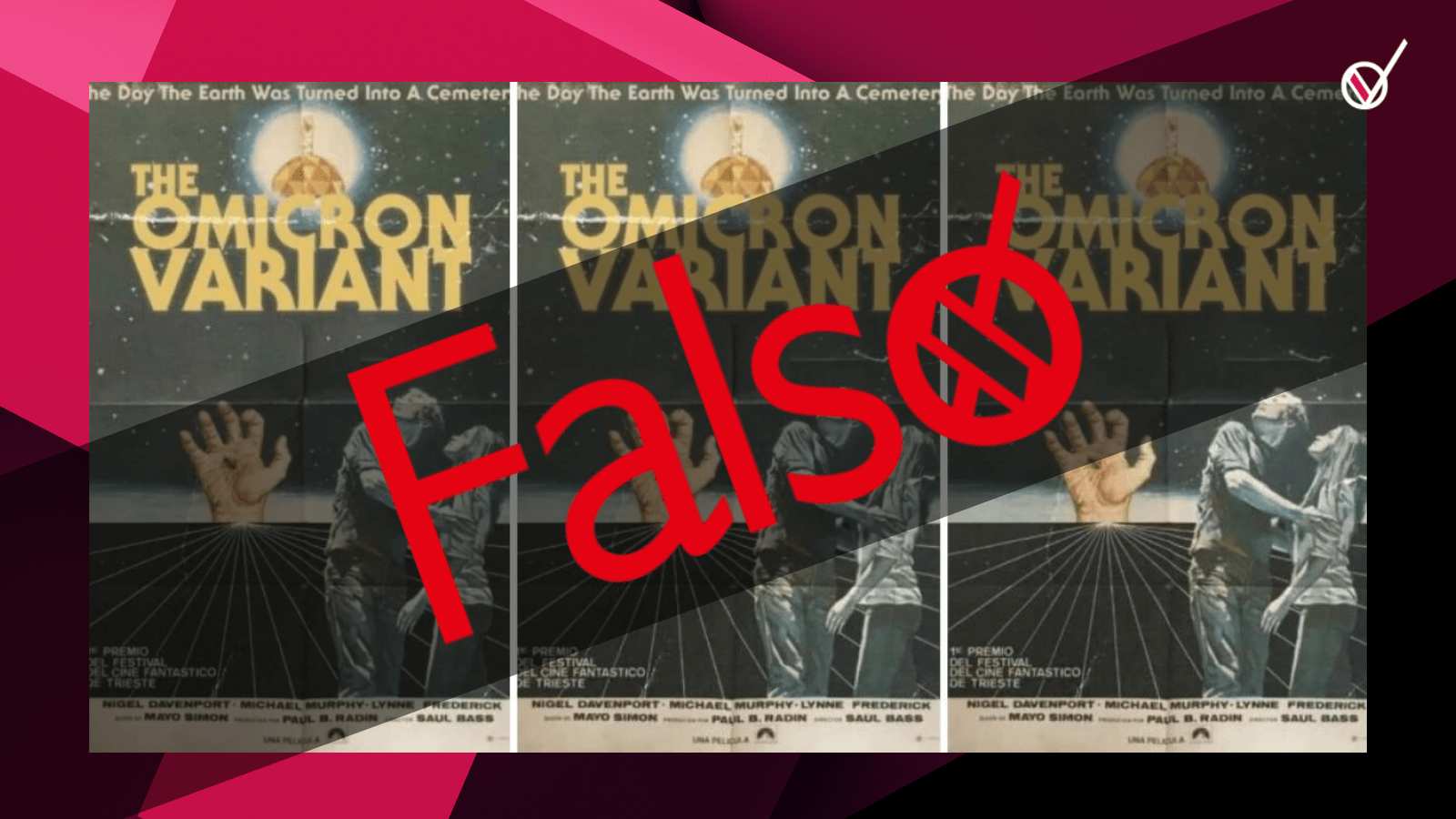

The Pope shared a joint with a Bolivian President. Drinking bleach is a cure for coronavirus. Vaccinations increase your chance of developing AIDS. A 1960s sci-fi movie predicted the arrival of the Omicron variant.

Viral disinformation straddles the spectrum from comically absurd to dangerously misleading: it’s a tsunami of online content which has hit Latin America hard, and with dire consequences – both personal and political.

Latin America is home to over 430 million internet users (a number which has doubled in the last decade) and has one of the world’s highest rates of social media use – as well as a young population. Its citizens are particularly prone to getting their news on social media and messaging apps like WhatsApp.

In a pandemic, information becomes a life or death issue: social media and WhatsApp groups across the region were suddenly full of home recipes for prevention and cures to the virus, like bananas, eucalyptus vapors, lemon juice, and (of course) agua panela (sugarcane water) – or even bleach – as well as disinformation about vaccines, including conspiracies about mind control chips, satanism, or fetal cells.

Just as dangerous as pandemic pseudoscience have been conspiracy theories about ethnic minorities spreading the disease and hate speech which has translated into real world violence – though this type of content pre-dates the health crisis.

“A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes”

The idea of a ‘post-truth era’ has emerged, but propaganda and lies are nothing new to any region of the world, it’s just that internet access and a barely-regulated online world have made it more infectious than at any time in history. Falling levels of trust in traditional media have pushed people further onto social media and alternative sources of information.

A strongman’s best friend

‘Fake News’ is an expression popularized by former US President Donald Trump, but has echoed across the globe. Across a multitude of themes and almost all social media platforms, the problem is ubiquitous – but tackling it has proven to be like fighting smoke.

The new wave of ‘strongman’ populist leaders on the continent are big on social media. Lopez Obrador, Bolsonaro, and El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele tend to speak directly to their followers via Facebook Lives and YouTube, often with little accountability for what they publish or broadcast.

“It has attacked the credibility of journalism.”

Nearly four out of every ten verifiable statements President Andrés Manuel López Obrador made during his second year in office were not true, according to Mexico’s Verificado group. Many of these statements were made during his morning press conferences, broadcast on YouTube and watched by millions. All this while accusing journalists of ‘fake news’ during the very same broadcasts, which the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights had to step in and ask him to stop doing.

In a speech in September, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro said, “Who never told a little lie to their girlfriend? If you didn’t, the night wouldn’t end well,” he said, to laughs from an audience of his supporters, continuing, “Fake news is part of our lives.”

Evidence of a huge-scale professional pro-government disinformation operation has emerged in Brazil, while it seems neither Supreme Court lawsuits nor being suspended from YouTube can hamper Bolsonaro’s appetite for the ‘little lie’.

Guilherme Amado, political journalist and Deputy Director of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism, tells Latin America Reports that Bolonsaro attacks journalists – including himself – every week on his social media broadcasts, and lies with no accountability. In Brazil, disinformation and its sources have gained more trust than journalists amid Bolsonaro’s open disdain for the profession, making life harder for those trying to inform.

“It has attacked the credibility of journalism. Even when we do everything the best we can, the article is right, it’s fact-checked, based on documents, trustworthy sources, readers maybe still don’t believe us – maybe because they are so biased, inside their bubble of disinformation, that they simply don’t trust journalism any more – it is the worst thing.”

Sensationalist disinformation is wielded for political gain – rumors spread about opposition politicians can do real damage at the polls – either by getting people to vote based on lies or anger, or by dissuading them from voting at all. The use of disinformation in the biggest referendum in Colombia’s history gave birth to one of Latin America’s biggest fact checking groups:

“Colombiacheck started five years ago after the referendum on the peace deal with the FARC – the ‘No’ campaign won by a small margin – their strategy was to get people to vote in anger, and they’d achieved that anger with disinformation,” Jeanfreddy Gutierrez, Director of Colombiacheck, told Latin America Reports.

“It’s important to note that 2016 was also the election of Trump after his comparable campaign – what was happening in the world arrived in Colombia – it was something urgent. With the pandemic, we were yet again passing through the same thing.”

Disinformation has arrived in Latin America from all across the world: some regimes invest huge resources in cross border disinformation and propaganda. A new study from the Global Americans found that the governments of China and Russia (and to a lesser extent, Cuba, Venezuela, and Iran) actively and intentionally provide disinformation to audiences in Latin America through state-run outlets which publish in Spanish – like Sputnik Mundo, RT en Español, and Xinhua, as well as social media and YouTube channels.

These campaigns are carried out with a range of diplomatic, economic, and political aims – often seeking to discredit the USA and posit their own regimes as preferable allies.

Truth or Lies – who decides?

Several Latin American countries are moving to criminalize the dissemination of fake news, with sentences of up to 10 years in nations like Bolivia and Nicaragua. Critics say these laws are often just tools for political persecution, and it hasn’t taken long for that to prove itself true.

In preparation for this year’s elections, incumbent President Daniel Ortega weaponized ‘fake news’ laws to imprison journalists in Nicaragua, while his own regime was running ‘troll farms’ – thousands of fake accounts spreading disinformation across numerous social media platforms.

Other proposals for making ‘fake news’ a criminal offense are in process in Chile, Colombia, Panama, and El Salvador. Last year alone, there were at least 17 new laws on disinformation and ‘fake news’ worldwide: some are criminal laws, some impose fines on media, others grant authorities power to force social media platforms to remove content.

But lying and well-intentioned wrongness can be hard to distinguish – differentiating honest mistakes from malicious lies and sanctioning the latter is a knotty business. If ‘misinformation’ (false information) and ‘disinformation’ (false information intentionally spread to cause harm) are problematically vague for policy-makers, ‘fake news’ is disastrously so.

Good faith attempts at law-making have been weak (poorly-defined, broad, vague, or all three, leaving laws wide open to abuse), but much worse is the wave of the not-so-good faith attempts: authoritarian leaders have started branding critical voices as ‘fake news’ in attempts to silence, stigmatize, and criminalize journalists.

Out of the frying pan, into the Zuck

Whether social media corporations are a better option than state regulation is up for debate – both approaches have people up in arms, from human rights campaigns to international bodies like the UN.

A new patchwork of policies emerged in the pandemic: trusted institutions were linked, and disinformation was downranked, flagged or removed, while certain topics were de-monetized. Twitter even deleted tweets from major political figures such as Bolsonaro and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

The engagement with the issue, after years of campaigning by civil society about hate speech and fake news, seemed a step in the right direction, but the sudden and massive disappearance of content (often without even notifying authors, let alone explaining) started to feel sinister.

With more removals than ever – a higher proportion of which than ever now carried out by AI – the mass disappearance of content is cause for concern for freedom of expression, and until we break the equation of ‘clicks equals profit’, it’s hard to see that much will really change – much less when profits look like Facebook’s do even amid a global crisis.

Are facts… sexy enough?

There are now at least 24 fact checker initiatives in Latin America and the Caribbean, but they’ve got their work cut out. Government fact checking bodies lack funds and often independence, so independent think tanks and charities are now facing that tide. Fact checkers like Colombiacheck or Argentina’s Chequeado work around the clock checking and correcting rumors and even official statements.

“We are using the strategies of the Bad Guys”

“This year, the amount of political disinformation during the national protests overwhelmed our institutional capacity– we couldn’t handle it. During those months, we just couldn’t verify everything we found” Gutierrez, Director of Colombiacheck, said.

“For next year, for the election, we are doubling our team, we are going to create a national network with 50 communications media, but disinformation continues to grow. Political and religious groups have also adopted it as a strategy, particularly around anti-vaccination campaigns.”

And in a polarized environment, even fact checks become politicized, says Gutierrez, “When we publish a political correction, half the country says thank you, the other half calls us traitors. The audience is so polarized.”

Some even face abuse and threats for their work – Brazilian fact checking organization Lupa received as many as 56,000 threats per month in 2018 – from across the ideological spectrum, though the majority are Bolsonaro supporters, and around 20% are bot-generated. Another fact checker in Brazil, Truco, closed down amid threats.

& Moises Flores. Image courtesy of Radio Sonica.

“A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes,” (ironically, nobody even seems to be able to agree who to attribute the quote to), but we now have scientific proof that a lie spreads faster than the truth: three times faster on Twitter. Fake news – much like extremist content – is more exciting, more outrageous – it garners more clicks and makes more money for advertisers.

So how do checks and corrections compete to reach the same audience consuming disinformation? Barrientos and Gutierrez both say that ‘viral tactics’ are the key.

“We are using the strategies of the ‘Bad Guys’. We are using memes, infographics – viral techniques. Fact checkers need to learn to be ‘sexy’ – so it’s TikTok, memes, WhatsApp audios done by actors,” says Guttierez.

Grassroots initiatives are springing up too, like ‘Under the Magnifying Glass’, run by Radio Sonica in Guatemala, a youth radio station. They discuss and debunk the rumors their listeners send in, directly reaching young people in a country where the mainstream media too often fails them.

“We rank trending stories – true, false, or impossible to verify – we have also created a verification guide to help people do it themselves. Young people need to not believe the first thing they read, to compare sources and media,” says Gilda Barrientos, founder of Under the Magnifying Glass.

“In a country like Guatemala, it’s so important – we need youth to understand that media have economic and political interests – even personal interests – and with the pandemic, the problem has grown a lot: media prioritize immediacy over quality.”

The team even translates content into Guatemala’s indigenous Mayan languages, as 40% of Guatemalans do not speak Spanish as a first language, making information access even harder in a country whose mainstream media do not take those communities into account.

“There is a demand for verification among young people here – it gets their attention, we have a lot of reach. We can see that they are being viewed and shared – some are even saving that content to their phones,” says Barrientos.

But the problem is just too big for any one organization to cover, and not all of it can even be seen or tracked. Bigger groups like Colombiacheck work in collaboration with giants like Facebook and Twitter as part of joint initiatives, and still only feel they’re scratching the surface.

“We barely check one part of the amount of disinformation out there: there’s so much we can’t see – Telegram, private Facebook groups, alternative social media – WhatsApp doesn’t allow us to monitor what content is being most shared,” says Gutierrez.

Is the worst still to come?

Though the threats posed by disinformation are very real, just as real are the threats posed by cries of ‘fake news’ which open the doors to state-controlled information or to huge social media corporations deciding what content we see, or silently disappearing thousands of posts without explanation.

So it seems like we, the readers, have to be on our guard, checking multiple sources, questioning the origins of our information, checking before we share – but do people have the time? Or the inclination?

“We are going to start seeing deep fakes in Latin America”

Journalists themselves have to do their part, and work to prove themselves to readers, says Amado,

“I’m sure that disinformation has a responsibility in this crisis of credibility, but we journalists also have a responsibility. We have to develop ways to win the trust of readers again, start the conversation again, maybe develop ways of listening to them better, hearing their criticism and paying attention to what they say.”

The importance of media literacy is finally being recognized in some places. The state of São Paulo in Brazil included media literacy as an elective class in schools to help students recognize what is news and how to check sources. Argentina’s fact-checking group Chequeado put together a handbook with UNESCO to help train others to spot disinformation.

Radio Sonica also runs ‘House of Lies’ – pop-up media literacy workshops for young people. It’s easier said than done, though, in a region where basic literacy is lacking in many places.

“We also have a big population here who don’t even have primary education, so how are they going to have media literacy training? How can they be expected to read the media critically? It’s much harder in those cases.” says Barrientos.

It’s slow stuff, and time is not a luxury the region has, with key elections over the next year in Chile, Colombia and Brazil. But worse is yet to come, warns Guttierrez.

“We are going to start seeing deep fakes in Latin America – we suspect they’ll be manipulated videos which seem to show politicians saying controversial things. We already have false tweets or sites which imitate newspapers, but they’re easy to spot – with deep fakes we confront a more difficult issue.”

Fake news flourishes in darkness, and as societies across the continent – and the world – become more polarized, fake news proliferates, and people retreat ever-deeper into their dingy online echo chambers. If sunshine is the best disinfectant, we’ll need to come out into the light soon – but it’s all of our jobs, says Gutierrez:

“Nobody can afford to hang back from this issue in our new digital ecosystem.”