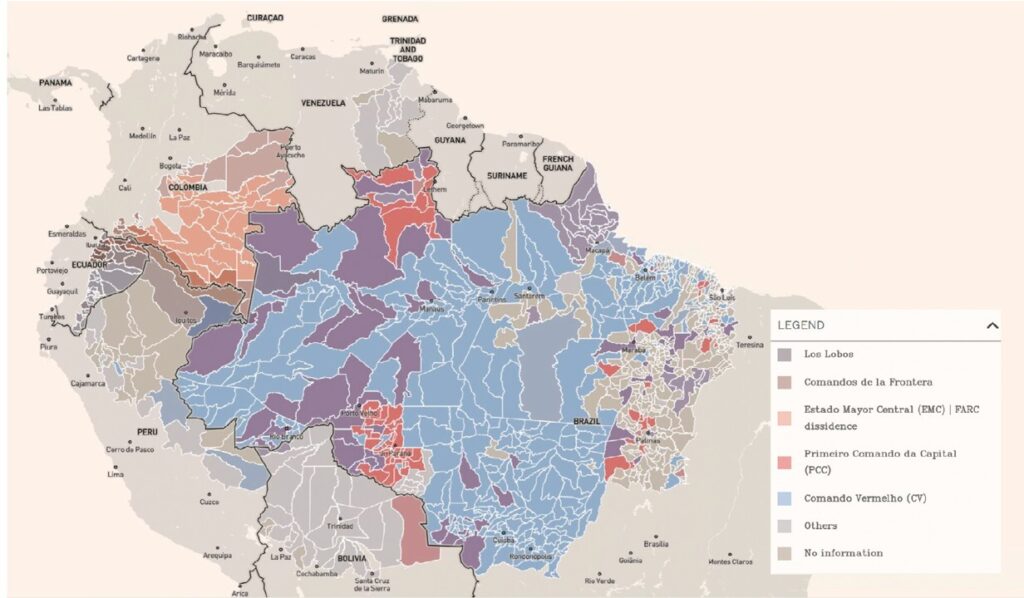

Bogotá, Colombia – The Amazon river basin has been taken over by armed groups in a massive scramble for illegal resources and trafficking routes, according to an investigative report by Amazon Underworld, a cross-border alliance of journalists and crime investigators.

Organized crime groups, some under the banner of guerrilla armies, are present in at least 67% of municipalities across Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela.

The report, based on analysis of 987 municipalities – each of which often cover vast areas of river and rainforest — revealed a dramatic expansion of crime across territories critical to global climate stability.

“Criminal activity in the Amazon deserves more attention on the global climate agenda, as it has become a major obstacle to preserving one of the world’s most important ecological assets and climate regulators,” Bram Ebus, founder of Amazon Underworld, told Latin American Reports this week.

The rainforest, the world’s largest, has increasingly become hostile, according to Amazon Under Attack: Mapping Crime Throughout World’s Largest Rainforest, the result of research into 987 municipalities.

Of these, 662 (67%) had at least one armed group present, and of these 211 municipalities had two or more gangs roaming the jungle, signifying increased risks for civilian populations stuck between competing combatants.

“Latin America is the world’s most violent continent, but homicide rates in the Amazon far exceed regional averages, especially when myriad armed groups vie for territorial control,” said Ebus.

Crime without borders

The investigators identified seven major crime groups operating across international borders, complicating law enforcement efforts.

These included Colombia’s Comandos de La Frontera, formed by former FARC fighters, which had spread deep into Ecuador with drug labs and training camps, and even operated trafficking corridors in Pacific port cities such as Guayaquil. The group also has a presence in Peru and Brazil, said the report.

Another transnational gang was Brazil’s Comando Vermelho (‘Red Command’) which had spread into Bolivia and Peru with presence in a whopping 403 municipalities across three countries. Its operations included cocaine production deep in Peruvian territory and illegal gold mining.

Image credit: Antonio Melgarejo via Amazon Underworld.

Smaller, but no less dangerous, was rival Brazilian gang PCC (Primeiro Comando da Capital) which originated in the distant metropolis of São Paolo but now also operates along the Amazon River and its tributaries into Venezuela and had close links to Colombian armed groups.

The PCC had transformed Brazilian ports into “critical transit hubs for international drug trafficking” and was instrumental in supplying Europe’s cocaine market valued at an estimated US$12 billion a year, the Amazon Underworld report stated.

The investigation’s findings were released to coincide with next month’s UN climate conference COP 30 taking place in the city of Belém, Brazil, at the mouth of the Amazon.

Ebus said that there was a growing recognition that organized crime was a major threat to Amazon conservation and climate goals. However, there were few serious efforts at building integrated state responses.

“Organized crime thrives along Amazon borders, where groups meet and multiply, easily moving across international boundaries to evade crackdowns,” he said.

Criminal activity was a “major obstacle to preserving one of the world’s most important ecological assets and climate regulators,” he added.

Population impact

Human populations were also devastated by the crime wave, according to Amazon Underworld’s research. Particularly in Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador, competition between armed groups was causing displacement of communities and targeting of civilian leaders.

In Colombia, more than 9 million people lived under the shadow of armed groups, according to UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) data, and Ecuador’s Amazon provinces had seen homicide rates increase fivefold in just four years, said Ebus.

In Venezuela state forces openly collaborated with Colombian guerrilla groups to strip natural resources from high-biodiversity areas, also creating anarchy for nearby communities.

Meanwhile armed groups bullied communities, forcing them into silence, and recruited young people into their criminal ranks with offers of illegal wealth. Local leaders who stood up to the gangs were threatened or killed.

In most countries gangs had corrupted state institutions with local police and army often in cahoots with the criminals or were bribed to turn a blind eye.

This put the task of environmental protection on civilians in frontline communities, particularly Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and campesino populations, who attempted against all odds to monitor vast rainforest territories through self-organized patrols, said the report.

Indigenous communities were once seen as effective forest guardians, according to the report, but now faced escalating threats as they resisted criminal expansion.

“This makes them primary targets for criminal organizations, especially where state presence is weakest or law enforcement has been compromised,” it said.

Perverse incentives

Part of the problem facing the Amazon was that many areas of the vast watershed had never been fully governed, Ebus told Latin America Reports.

“It’s hard to speak about state abandonment when states have never been present in the first place.”

Perhaps paradoxically, some areas like the Colombian Amazon had historically benefitted from armed group presence, he explained. “Armed groups in Colombia have occasionally curbed deforestation to advance political dialogues or to maintain jungle cover for protection and operational secrecy.”

More recently, green schemes such as payments for carbon credits had provided perverse economic incentives for armed groups to extort populations receiving these benefits, which could in theory motivate criminal groups to limit environmental damage to maximize extortion payments, said Ebus.

But in the broader picture, these groups overwhelmingly escalated environmental harm, he added, as criminal economies depended on land grabbing, cattle ranching, and illegal gold mining, partly to launder and recycle profits from cocaine trafficking.

The region now required urgent transnational cooperation to counter “organized crime networks that now dominate vast territories”.

The Amazon was “facing a fierce test”, he concluded.

Featured image: The Caquetá River close to the Colombian border with Brazil, a major drug trafficking route.

Image credit: Steve Hide.