United States President Donald Trump is directly influencing Honduras’s election. After endorsing conservative candidate Nasry Asfura, Trump pardoned former President Juan Orlando Hernández of Asfura’s National Party — who was serving a 45-year sentence in the U.S. for drug trafficking — and threatened to cut off aid to Honduras if his preferred candidate lost.

After Honduras’s National Electoral Council (CNE) declared a “technical tie” between Asfura and centrist candidate Salvador Nasralla as vote counting continued, Trump posted on Truth Social, “Looks like Honduras is trying to change the results of their Presidential Election. If they do, there will be hell to pay!”

Ricardo Zúñiga—a Honduran-born U.S. diplomat who served as former President Joe Biden’s special envoy to Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras—commented on Trump’s involvement: “The race isn’t over… But I think the endorsement clearly tilted the undecideds toward Asfura.”

The election remains undecided and the CNE has up to 30 days after the election to deliver a result or order a recount. The ongoing contention forbodes potentially violent disputed results, as occurred in 2017.

But undeniable in this election has been Trump’s influence. His endorsement, pardon, and threats could prove decisive if Asfura wins—a very possible outcome as the race maintains a razor-thin margin. Moreover, Trump’s unilateral decision-making towards Honduras and other individual countries reveal what his new Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine looks like in practice—a new stage of interventionism in Latin America with 21st century tactics.

Why does Trump care about Hondurans’ election?

U.S. intervention in Honduran politics has a long history. Referencing the Monroe Doctrine, a U.S. strategic policy since 1823 to oppose extrahemispheric intervention in the Americas, Theodore Roosevelt in 1905 issued his own Corollary and endorsed exerting “international police power” to secure interests in the Caribbean Basin.

His presidency oversaw military incursions in Panama, Cuba, and Honduras. His successor, William Howard Taft, pledged a new policy of “substituting dollars for bullets” in 1912. But over the next two decades, the U.S. still intervened militarily in Mexico, Nicaragua, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and repeatedly in Honduras to collect debts and ensure favorable conditions for U.S. firms, including the United Fruit Company. (It was the U.S. fruit companies’ influence in Honduras that inspired author O. Henry to coin the term “banana republic” in 1904.)

U.S. power projection in Honduras continued through the Cold War. Pro-U.S. Honduran presidents gave training ground for a CIA-backed coup that overthrew Guatemala’s president in 1954 and Nicaraguan Contra insurgents after the Soviet-backed Sandinistas seized power in 1979. U.S. Ambassador to Honduras from 1981 to 1985, John Negroponte—a top national security official in the Nixon, Reagan, and both Bush administrations—facilitated so much military aid that many called Honduras an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” for U.S. operations against the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and leftist guerillas in El Salvador and Guatemala.

Honduras has remained crucial for U.S. strategic priorities. Since 1983, Honduras’s Soto Cano Air Base in Comayagua has been home to Joint Task Force Bravo, the expeditionary force of U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) that leads counternarcotics and disaster relief missions. With Honduras being a drug trafficking hub, a migrant transit node and a prime source of U.S.-destined migrants, effectively countering transnational crime and addressing regional migration necessitates security cooperation with Tegucigalpa.

Complicating bilateral cooperation has been Honduras’s party in power: Libertad y Refundación (LIBRE). The Party is led by President Xiomara Castro, wife of left-wing President Manuel Zelaya who was deposed in a 2009 coup after backing likeminded Venezuelan populist Hugo Chávez and seeking an unconstitutional second term. After showing promise towards Washington in 2022, Castro has sent officials to meet with Venezuela’s alleged drug-trafficking defense minister, terminated a bilateral extradition treaty, and threatened to end defense cooperation.

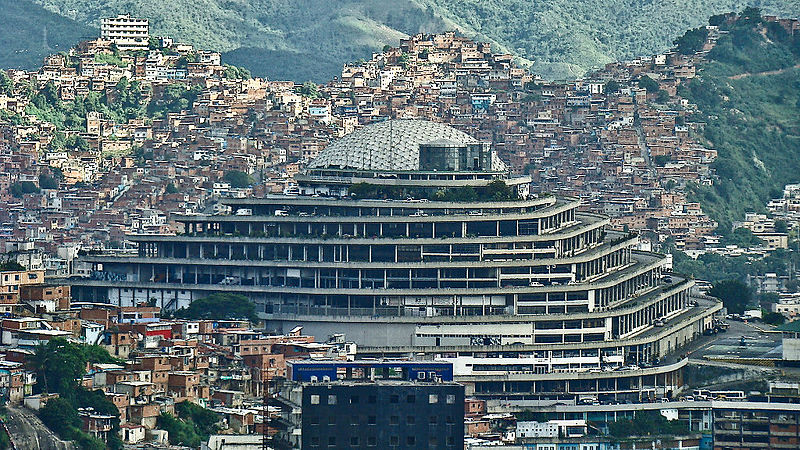

Along with Russia, China, Iran, Cuba, Nicaragua, and North Korea, Castro recognized Nicolás Maduro’s stolen election last year in Venezuela while the Biden administration, regional allies, and European democracies condemned the blatant fraud and subsequent repression.

Castro’s Defense Minister and LIBRE’s current presidential candidate, Rixi Moncada, congratulated Maduro on a “historic triumph” and pledged solidarity with his government. As the U.S. since 2018 has sought to end Maduro’s dictatorship, a LIBRE defeat would remove a regional ally of Maduro’s kleptocratic, drug-trafficking regime that has destabilized the Western Hemisphere.

Further aggravating was Castro in March 2023 making Honduras the latest Latin American country to establish relations with China and sever relations with Taiwan, which now has only 12 diplomatic allies. Castro did so despite requests to maintain relations with Taiwan from Biden’s Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs and then-Senator Marco Rubio.

Both Asfura and Nasralla have endorsed switching back to Taiwan if elected, further incentivizing the Trump administration to oppose the pro-China LIBRE party. As preserving Taiwan’s diplomatic allies and countering China’s influence in the Americas are bipartisan priorities, a non-LIBRE victory doubly benefits Washington’s interests, and could make Honduras the first country to re-recognize Taiwan since Caribbean island-nation St. Lucia in 2007.

Rubio acknowledged Honduras’s deportation cooperation in February, and Castro has reinstated the extradition treaty and in June met with Homeland Secretary Kristi Noem. But Castro approaching Caracas and Beijing—plus the strategic potential for a pro-Washington government in Tegucigalpa—has moved the Trump administration to seek political change in Honduras. In pursuit of this goal, Trump has endorsed a candidate, pardoned a former president, and alleged an electoral theft.

Why do Hondurans care about Trump’s endorsement?

With an over-60% poverty rate, decades of pervasive corruption, and the fourth-highest homicide rate in the Americas from rampant gang violence, Honduran electoral priorities concern economic development, citizen security, and corruption prevention.

But maintaining positive relations with the U.S. is also on the ballot. By far Honduras’s largest export market, the U.S. provides hundreds of millions in annual aid, even after USAID’s shutdown. While Trump’s pardon may frustrate voters’ anti-corruption wishes, the current government’s scandals do not present clean alternatives. And with SOUTHCOM providing life-saving humanitarian relief to devastating and frequent hurricanes, losing U.S. support seems unwise to many voters. Zúñiga stated on Trump’s intervention, “Hondurans as a society do not want conflict with the United States. I think that’s a factor.”

Though as U.S.-originated remittances provide more than 25% of Honduras’s GDP, Trump’s deportation plans do not bode well economically for many Hondurans. Trump-endorsed Asfura has simultaneously lamented deportations and worsened U.S. relations.

Honduras is not the only country where Trump has significantly influenced elections. In Argentina in October, right-wing populist Javier Milei swept decisive midterms that preserved his inflation-reducing austerity policies after Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent announced a $20-billion credit swap, later doubled to $40-billion with private sector contributions, to strengthen the Argentine peso and thereby restore faith in Milei’s then-teetering government.

The U.S. has performed similar financial interventions before, but never so clearly to influence an upcoming election. And while Trump’s benevolence was politically-motivated, conditional on victory, and opposed domestically, his intervention critically boosted Milei’s domestic support and served bipartisan U.S. priorities, including securing critical minerals and countering China’s influence.

Argentina and Honduras are also clearly part of a regional trend toward conservatism. Between Venezuela’s collapse, stagnant growth, and rising insecurity, right-of-center candidates—who unfailingly align with Washington—have won major elections in El Salvador, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Chile since last year.

This wave appears a reversal of the early 2000s Pink Tide, when populist leftist governments swept the region and frequently opposed cooperation with Washington. These new governments have quickly built stronger ties with the U.S., as demonstrated in Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau’s visit last month to the inauguration of Bolivian President Rodrigo Paz, whose center-right government ended 20 years of socialist governments often hostile to Washington. LIBRE’s left-wing candidate has received less than 20% of counted votes.

Asfura has signaled himself as part of this movement, tweeting a graphic of him, Trump, and Milei in November.

Tactics of the ‘Donroe Doctrine’

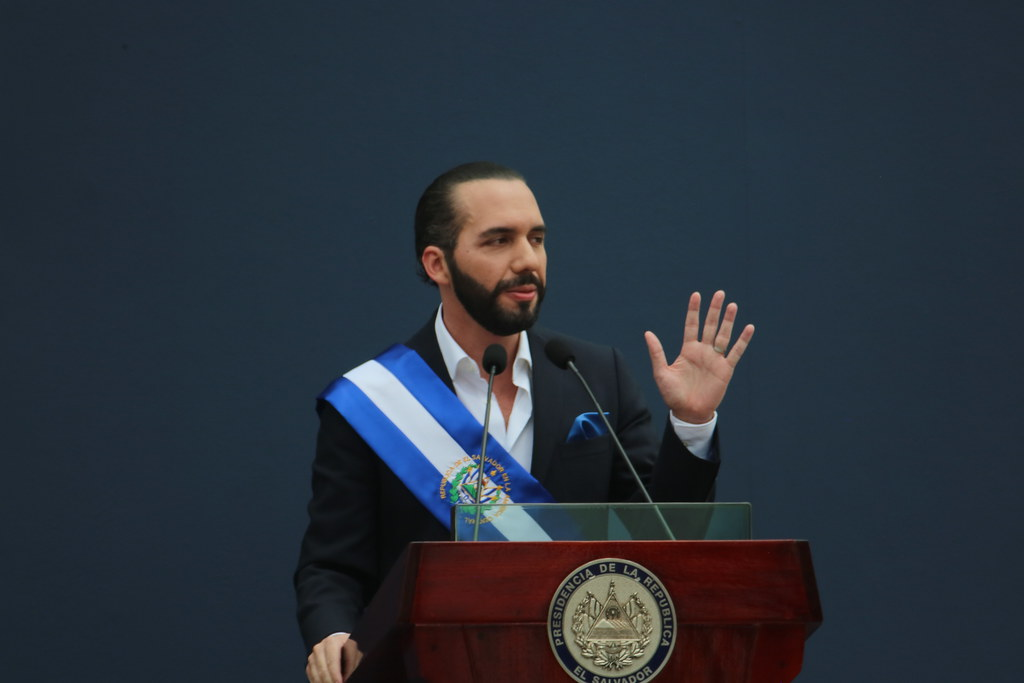

It is not unprecedented for the U.S. government to express favored outcomes in Central American politics. The Biden administration denounced Salvadoran strongman Nayib Bukele’s power-consolidating moves, added many names to the Engel List of sanctioned Central American officials, and intervened diplomatically in the 2023 Guatemalan election—sanctioning more than 100 Guatemalan congressmembers—to ensure Bernardo Arévalo’s inauguration against corrupt efforts to overturn his electoral victory.

But Trump’s methods of influencing Latin American politics are unilateral, forceful, and novel. On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump contemplated bombing drug cartels within Mexico, then commented in November that such strikes were “OK with me” and that he would be “proud” to target cocaine laboratories in Colombia.

In his inaugural address in January, Trump stated that China was “operating the Panama Canal” and pledged to retake the waterway before Rubio persuaded Panamanian president Raúl Mulino to make Panama exit China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Trump has repeatedly feuded with Colombia’s leftist President Gustavo Petro—revoking his visa, calling him an “illegal drug leader”, levying sanctions on him, and decertifying Colombia as a counternarcotics partner after Petro told U.S. soldiers to “disobey” orders at a pro-Palestine rally in New York and decried the Caribbean bombings. And most notably, Trump has escalated U.S. policy against Maduro through the largest Caribbean military activity since the 1989 invasion of Panama.

Experts have called Trump’s hemispheric policy the “Donroe Doctrine” in reference to the aforementioned historic policy of expelling external intervention. On December 2, Trump explicitly endorsed the Doctrine by issuing his Corollary. In the announcement, Trump asserted that “the American people—not foreign nations nor globalist institutions—will always control their own destiny in our hemisphere” and identified drug flows, illegal immigration, and “narco-terrorist networks” as critical national security challenges. Two days later, Trump issued a new National Security Strategy, which cited his Corollary and promised that the U.S. “will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere.”

But Trump’s hemispheric strategy also includes carrots for U.S.-aligned governments. Governments both left and right of center in Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador have greatly increased partnerships with the U.S. this year. Even Brazil—where Trump imposed 50% tariffs for prosecuting former right-wing populist president Jair Bolsonaro over coup plotting—has since seen significantly warmed relations.

Trump’s actions, of course, are not well-received among many Latin American and U.S. political leaders. Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum has repeatedly rebuked Trump’s threats to strike drug cartels within Mexican territory, and Petro is not alone among Latin American officials opposing the boat strikes. Within the U.S., Trump’s financial intervention in Argentina drew sharp criticism from both Democrats and Republicans, as have the boat strikes, and Senators from both parties have criticized his pardoning of Hernández, which right-wing lobbyist Roger Stone apparently influenced. On December 10, Honduras’s CNE commented, “We absolutely condemn the interference of the President of the United States, Donald Trump.”

But regardless of their perception, Trump’s Latin American policies mark a notable strategic shift. In an interview on December 2, Rubio remarked on the Caribbean military activity, “If you’re focused on America and America First, you start with your own hemisphere where we live… what happens in our hemisphere impacts us faster, and more deeply, than something that is happening halfway around the world.” Rubio’s commitment and the new National Security Strategy—which places the Western Hemisphere front and center for the first time—indicate that Trump’s fixation on the Americas is poised to continue, using his unprecedented policy toolbox.

In the Gunboat Diplomacy era, Washington used multiyear occupations to bolster and even install aligned governments in the Americas. These tactics evolved to include covert action, developmental assistance, and three unilateral interventions during the Cold War, then targeted sanctions, visa revocations, and diplomatic negotiations since. They now include social media posts, bilateral currency swaps, and drone strike threats.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump via X.