Bárbara Martins is a 21-year-old journalism student at Rio de Janeiro’s Federal University (UFRJ) who is worried that recent government cuts to the education budget will mean she will not be able to finish her second university semester of the year.

“It’s the biggest university in the country, there is no way it is going to be able to operate with almost halved funding,” Martins told Latin America Reports.

Earlier this month, students and employees of Brazilian public education institutions received news of the current government’s decision to freeze approximately 23 percent of the country’s discretionary education budget, equivalent to approximately $5.8 billion Brazilian reais (US $1.4 billion). Just under half of this would have been allocated to public universities.

Of this amount, around 30 percent of university maintenance costs will be cut. With the support of Minister of Education Abraham Weintraub, President Jair Bolsonaro also plans to freeze around 3,500 postgraduate scholarships across the country.

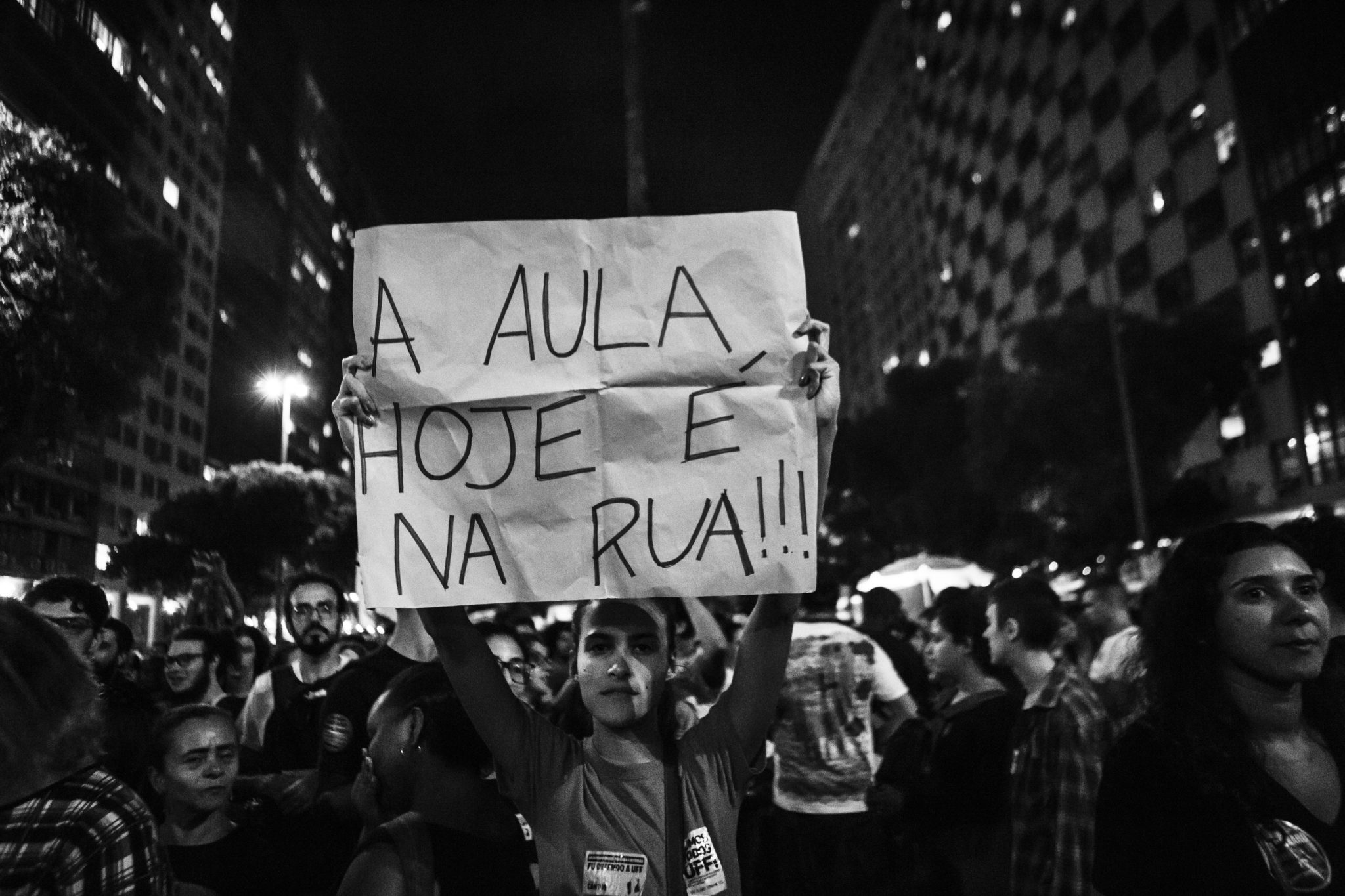

In response to the policy cuts, tens of thousands took to the streets on May 15, after the National Student Union called for large-scale protests in around 170 cities across the country. Further protests, which according to social media promise to be bigger, are due to take place tomorrow, May 30.

(Ana Carolina Fernandes)

For 20-year-old Rio de Janeiro Federal University (UNIRIO) medical student Bruno Fernando, the austerity measures will almost certainly directly impact his studies.

“The equipment we use in the hospital needs to be renewed frequently in order to care for the patients,” he said. “Without the ability for us to buy basic things such as gauze, adhesive plaster and needles … it’s impossible to carry out basic health procedures, preventing the population from being cared for and students from learning.”

The current government favors medical faculties for the immediate return they generate, along with veterinary and engineering departments. Other schools, such as philosophy and sociology, will be subject to a “decentralization of investment,” the president declared, which will be directed towards more profitable faculties.

Scientific department buildings are already in much better condition than other buildings, such as humanities, points out 19-year-old UFRJ engineering student Gabriel Vianna.

“My building is good,” he said. “It has a lot of investment from foreign companies, etc. because it is a technology building.” Others, such as the faculty of arts, have limited access to water, Vianna pointed out.

“If you walk past the technology department, you are going to see one UFRJ. If you walk past the literature department, the humanities department, the fine arts department, you are going to see a completely different UFRJ.”

Now, his university will be forced to cut back even further on basic maintenance to the buildings, affecting services such as water, lighting, security and general cleaning. Without this, Vianna explained, it will be impossible to study, even if all the educational resources are available.

“A university doesn’t just function through professors,” he said.

Vianna is not alone in his concern over cuts to basic maintenance costs. Twenty-one-year-old law student Manuela Fernandes who studies at Rio de Janeiro’s Federal Fluminense University (UFF) worries that cutting “non-obligatory” costs will have a major impact on the life of a state university student.

“Those who are aware of the realities of studying in a public university know how difficult it is to study in a place where there’s … no security to protect people (especially those who study at night),” she commented, adding that many pupils would not have the financial means to cover the already reduced-price food sold on campus if it were to increase in value.

The cuts won’t just affect undergraduates, but masters and postgraduate students as well, such as 36-year-old Carolina Caldas, who will have spent eight years in public university education by 2020. In the meantime, the UFF postgraduate political science student worries that the cuts will mean Brazil becomes more dependent on the scientific production of other countries, as opposed to its own.

The problem, in the eyes of engineering student Vianna, is that the current funding issues are the latest in a long line of consecutive cuts that have been affecting Brazilian public universities since 2016.

It is this level of neglect which has meant that public universities have long-since been unable to carry out sufficient levels of maintenance in place in order to prevent accidents, such as the devastating fire that swept through Brazil’s UFRJ-owned National Museum last year, which destroyed huge quantities of historical archives.

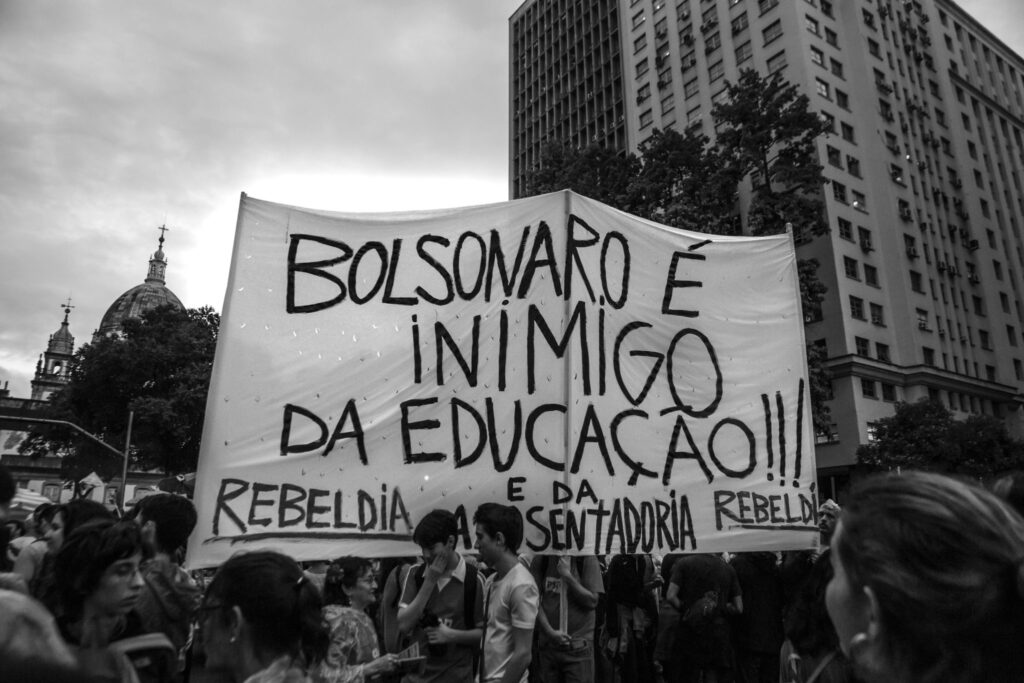

(Ana Carolina Fernandes)

Speaking to Brazil Reports in a previous interview, UFRJ Communication Director Amaury Fernandes attributes the lack of funds to the “savage model of privatization,” that Brazilian universities currently perpetuate.

For this reason, UFF political sciences professor Carlos Henrique Serra believes that the recently-announced austerity measures will generate a “collapse” in already under-funded Brazilian public universities.

The university’s rector Antonio Claudio Lucas da Nóbrega has already announced that without light and water, no quality research will be done, Serra told Latin America Reports.

“It’s about retaliation, resentment, a profound government hatred of public universities, because nothing justifies [the cuts],” Serra commented.

With his department set to be directly affected by the government’s “decentralization” of investment in humanities departments, Serra refers to it as “ideological persecution.”

“It shows a profound ignorance around the areas of philosophy and sociology as fields of knowledge,” Serra commented.

Speaking to journalists in Dallas whilst on a state visit to the United States earlier this month, Bolsonaro described the protestors as “useful idiots, imbeciles, who are being used as the maneuvering mass of a smart minority who make up the nucleus of many federal universities in Brazil.”

“If you ask for the water formula, they don’t know; they don’t know anything,” he added, referring to the students.

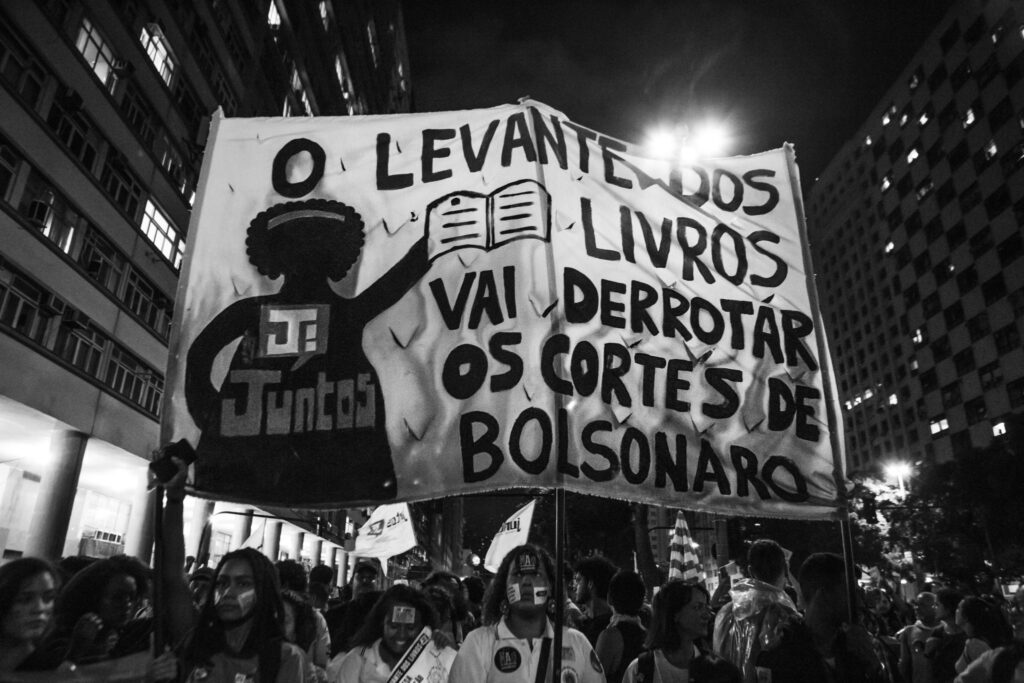

(Ana Carolina Fernandes)

Twenty-nine-year-old UFF political sciences postgraduate student Yanahê Fendeler Höelz believes that “when you start messing with education, you are messing with the ability to dream.”

“Education — which should be for everyone — is distancing itself further and further away from the dreams and concrete possibilities of many young people and families of this country,” she added.

Law student Fernandes agrees that education is fundamental for the development of a country, especially when that country is as unequal and exclusionary as Brazil.

Ana Carolina Fernandes is a Rio de Janeiro-based independent documentary photographer. Follow her on Instagram to keep up to date with her work.