Bogotá, Colombia – Colombia has won its key proposal to ease the war on drugs on the world stage – but victory could be short lived as the country risks US “de-certification” in its current attempts to control cocaine.

The resolution, backed by 63 countries, was adopted last week at the United Nations 68th session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs in Vienna, and widely seen as a major pushback against the prohibitionist approach to drug control.

Colombia asked the UN body tasked with policy on policing illegal drugs to create a “high level panel of independent experts to critically analyze the global drug regime,” which will report back in 2029. It could lead to decriminalization of products such as coca leaves currently classified as dangerous substances.

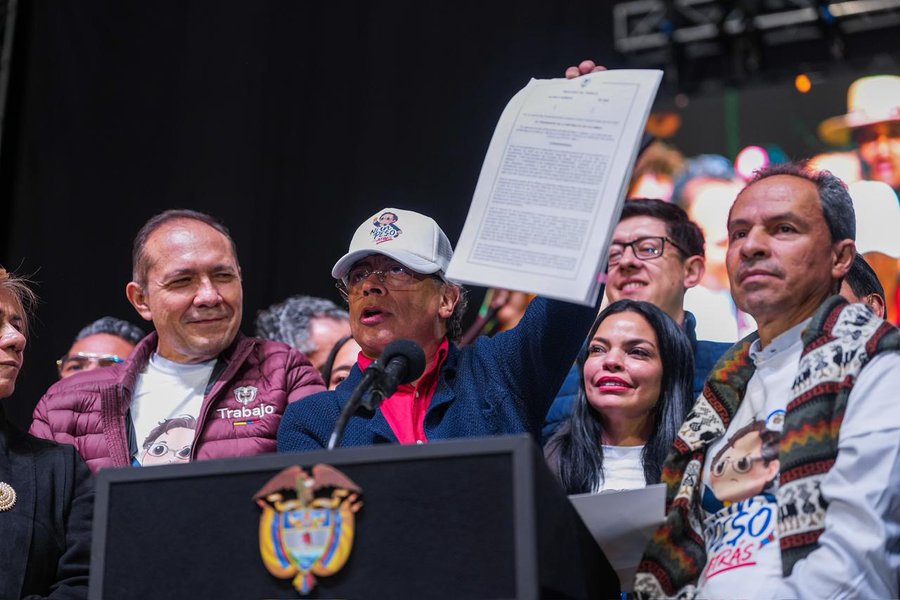

Meanwhile in Bogotá, President Gustavo Petro warned his cabinet during a televised debate that the United States, under President Donald Trump, would likely “decertify” Colombia in its struggle to combat cocaine, or use the threat to bring back aerial fumigation of herbicides to kill coca plants, banned in Colombia since 2015.

“They’re going to tell us to fumigate otherwise they won’t certify us. Spraying means killing farmers. And more war and more war in Colombia, more drug trafficking, and more migration to the United States. They’re creating a bad policy. It’s a policy of domination, not of comrades,” said Petro.

The two events highlight the dilemmas faced by Colombia in its decades-long fight against the cocaine trade, and its balancing act as an advocate to reduce punitive drug control while keeping the Trump administration on side.

Certification is a key issue for Colombia and other countries caught up in drug wars. Every year the US government approves drug control measures in a variety of countries and decertification, which hasn’t happened in Colombia since 1997, can bring sanctions, trade restrictions and a reduction in military and financial support.

Notably, the U.S. was one of only two countries (the other being Argentina) to vote against Colombia’s resolution at the UN conference last week.

Colombia’s policy since 2022 has been to offer communities voluntary programs to substitute their coca plantations with other commercial crops, while bringing social investment, what Petro described as “oxygenating” the coca regions.

Simultaneously Petro promised a strong program of drug captures – going after the bad guys – to “asphyxiate” the armed groups by cutting off their illegal profits.

Neither plan has succeeded. Monitoring by the UN recorded production potential of 2,600 tons of cocaine produced in Colombia in 2023, a 50% increase on the previous year, and coca crop coverage of a record high of 253,000 hectares. InsightCrime, which monitors organized crime in the Americas, called it Colombia’s “cocaine bonanza.”

With the global cocaine market being measured in hundreds of billions of U.S. dollars, and the high demand for the drug, some experts were questioning the success of crop substitution.

According to María Alejandra Vélez of the Center for Studies on Security and Drugs (CESED), talking to El Mutante recently, an evaluation of the coca substitution program found that only 3% of households had received the promised benefits until the end of 2022, with little progress since.

“And even if they manage to transform some territories and transition to other economies, the coca will move somewhere else,” said Vélez.

This so-called “balloon effect” – where coca crops squeezed in one area pop up elsewhere — has particularly affected areas of environmental protection, said Vélez. According to UN monitoring, 48% of Colombia’s coca crops are currently in national parks, forest reserves or indigenous territory.

She also challenged the government’s notion that eradicating coca would rid armed groups from a zone. CESED’s own fieldwork had shown that groups originally in the cocaine trade had diversified into other criminal enterprises such as the control of illegal gold mining, land appropriation and extortion. “This undermines the idea that coca necessarily creates the presence of armed groups,” she said.

Another analysis showed that drug interdiction in Colombia was failing to dent the cocaine trade. “Cocaine seizures are not putting any pressure on the illegal market,” concluded a report by Bogotá-based think tank Ideas Para La Paz late last year.

This was because police, army and customs strikes against the supply chain – the destruction of laboratories and confiscation of the drug itself or precursor chemicals – was not keeping pace with production.

“In 2023, 2,664 tons of cocaine were produced and 746 tons were seized; that is, 28% of the cocaine produced was seized. A reduction of almost ten percentage points compared to the proportion in 2022.”

Faced with these realities, Colombia stuck to its narrative in Vienna that current drug control policy was not working. “More of the same will get us nowhere,” Colombia’s ambassador to Austria Laura Gil , told the CND. She reminded the conference of Colombia’s commitment to the UN body, but also its desire for change.

“My country has sacrificed more lives than any other in the war on drugs imposed on us,” she told the 2,000 delegates from 100 participating countries. Colombia produced 70% of the world’s cocaine, which was 5% of the global illegal drug market, she said. “We’re not proud of this. We feel this weight on our shoulders.”

This weight was evident in Cauca this month as the state intensified its military operation in the Cañon del Micay, a coca-growing stronghold of armed groups.

On March 6, fighters from the FARC dissident armed group, the Frente Carlos Patiño, allegedly organized coca farmers to attack police and army units patrolling close to El Plateado, a town in the canyon, resulting in armored vehicles burned and 29 uniformed officers detained by the rioters.

They were released two days later, but the rebels then attacked an army convoy with a roadside bomb killing five soldiers and injuring 16 more.

The crisis in Cauca, running since last October, seems to have pushed Petro’s government towards a more military response than the softer solutions his diplomats were proposing in Vienna.

In early March, the mandate tweeted: “The Colombian army will never leave El Plateado or Micay. This is an irreversible decision because Micay does not belong to the Mexican cartels, but to Colombia. The military and social offensive must be doubled.”

He added: “We expect the freed campesinos to join the massive payment program for the eradication of coca plants.”

This tweet typifies the mixed message permeating the coca discourse in Colombia today. Two years into Petro’s administration, his substitution plan “has no clear strategy to achieve these goals across its components, nor an organized planning and implementation process,” reported Ideas Para La Paz.

The question now for Colombia is how will it tackle its growing coca crisis and declining security? Some believe the Petro administration will opt for a tougher approach to its coca enclaves even while promoting a gentler approach on the world stage. More military action might also improve his chance to avoid US de-certification.

The certification decision is due in September, though under Trump, punitive actions can come at any time, as happened with the tariff threats against Mexico.

Preliminary figures for cocaine seizures in 2024 look promising according to data released this month by the U.S. State Department in their 2025 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report: Colombian forces and international partners seized a record 960 tons of cocaine and cocaine base, a considerable increase from 2023.

The acid test will be coca crop coverage, with UN monitoring only reporting 2024 figures in mid 2025. Only then will it be clear if the record-setting interdictions actually outpace the increase in coca plantations.

For now, Colombia is pushing to get results on both fronts; disrupting the cocaine supply chain and reducing coca coverage. The race is on.

Featured image: A cocaine laboratory allegedly belonging to the National Liberation Army (ELN) which Colombian miliatary seized in February 2025. Image credit: Colombian Ministry of Defense via X: https://x.com/mindefensa/status/1892024800140231162/photo/3