Bogotá, Colombia – The sound of buzzing drones is sowing terror in Colombian communities under siege from unmanned aircraft flown remotely by rebels battling a high-tech state military.

Improvised devices, fashioned from commercially available drones, drop home-made bombs capable of killing and maiming. And there is growing evidence civilians are being deliberately targeted after a series of aerial attacks on towns and public spaces.

Last month in El Plateado, a town in the mountainous department of Cauca, a drone-dropped grenade exploded on a tented hospital set up by international medical organization Médecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), injuring local health workers.

“Events like these put the civilian population and the medical mission at risk, both protected by International Humanitarian Law,” said MSF following the attack.

But the next day, February 18, two more civilians, one an 80-year-old woman, were injured in the same town in a second attack by three drones dropping explosive charges into a residential barrio. And a week later in the rural area of El Plateado, 1,000 people were forced to flee their rural homes after crossfire between dissidents using drones and counterstrikes from the army.

“The dynamics of the conflict are no longer those long-term battles, as in the past, but the launching of explosives by both sides, between the public force and the armed groups, which have sometimes fallen on the homes of humble people,” local mayor Osman Guaco told La W Radio .

El Plateado is currently the epicenter of fighting between at least one irregular armed group formed by dissident FARC guerrillas and the Colombian military.

The town first came under drone attacks last June when aircraft flown remotely from a nearby hill dropped bombs on civilian structures, destroying houses and damaging a hardware store.

“A bomb fell here, on the entire roof. There were five of us, fortunately nothing happened to us, but we are very scared,” resident Jorge Ramos told local media at the time.

The same week a girl was injured by a similar grenade that fell in the nearby Cauca municipality of Suárez, while in the department’s main city Popayán, the mayor’s office temporarily banned the private use of drones after an attack with explosives against a police station.

The worst, however, was yet to come.

A grim milestone

In July, a 10-year-old boy was killed by a bomb dropped on the soccer pitch in El Plateado. He had been playing with friends and family at a social event. At least 12 others were injured, some seriously.

The incident was the first reported civilian death from a drone strike in Colombia, a grim milestone labelled at the time “a demented attack against the civilian population,” by army commander General Federico Mejia.

The general accused combatants from the Frente Carlos Patiño of the Central General Staff (EMC) FARC dissident group of targeting civilians as a form of “pressurizing the townsfolk to reject the presence of state military” in the town. This came as the state forces pushed into an area long dominated by rebel forces.

El Plateado sits astride access routes to the Cañon de Micay, a contested smuggling route down to the Pacific lowlands and major coca-growing region with 20,000 hectares planted along the canyon’s sides.

The region, previously held by the FARC guerrillas before their peace deal in 2016, has since been controlled by dissident EMC fighters now coming under intense military pressure.

The resulting surge in open conflict was prompting irregular armed groups to “find new ways to attack the troops that will allow them to obtain better results without losing their men in the confrontation,” a military investigator explained to newspaper El Colombiano last year.

Drone tactics copied from asymmetric wars in Ukraine and Sudan could give Colombia’s irregular forces a chance to even the playing field against a superior, hi-tech military.

The rise of the drones

In 2024, there were 115 drone attacks in Colombia, according to a report by the Ministry of Defense, mostly carried out by “criminal and terrorist groups against soldiers and installations.” Previous years had seen just a handful of incidents.

Military commanders voiced their concerns in March last year, and later released videos, purportedly intercepted by military intelligence, which showed these rebel units preparing and practicing with small commercially available drones, such as the DJI Pro 4, in some cases using bags of sugar to test the takeoff load.

Drones used so far have a maximum payload of one kilo (two pounds) which allows for an explosive charge of around 500 grams (half a pound) packed in a plastic pipe with nails as shrapnel. The finned bomb is suspended under the drone and released by a radio-controlled hook.

These designs follow a pattern long established by armed groups of making their own armaments from industrial dynamite and hardware from a local store.

Small missiles called tatucos are fired from plastic plumbing piping, and larger mortar rounds fashioned from gas cylinders. Landmines are made from soda cans or food containers.

This new generation of lightweight drone bombs “can flatten everything in a radius of five meters,” explained a community leader consulted by Latin America Reports, who had witnessed drone strike impacts.

He also noted that drones were increasingly used in combat between rival irregular groups, as seen in his region of Norte de Santander where the ELN guerrillas have been combating the Frente 33 (33rd Front), a FARC dissident group.

Last week army troops in the town there of Tibú uncovered an ELN arms cache including drones and explosives.

Drone wars between irregular groups in rural areas were likely to be masked from official statistics, the leader said, on condition of anonymity given the current tension in the region.

Aerial arms race

Insights into competition between rival armed groups to dominate airspace came from interviews with combatants in Nariño, in the southwest of the country.

In Nariño, the EMC is battling the Comuneros del Sur, an ELN-dissident group that entered into peace negotiations with the government last year.

When they [the EMC] “hear the drones they run away,” a Comuneros combatant told La Silla Vacia last year.

Drones had an outsized lethal impact compared to more expensive guns and ammunition, said Comuneros de Sur commander Gabriel Yepes.

The group was using drones costing around USD $1,200, capable of carrying explosives for a flight of 30 minutes and to a height of 500 meters (1,640 feet) where they are less detectable by ground troops.

“A well-aimed grenade can kill up to three or four of our enemies,” Yepes told La Silla Vacia.

The Comuneros del Sur had recruited a team of tech-savvy operators, known as droneros, considered vital to battlefield success, he said. “Our drone unit is the one we protect most.”

But he also admitted competition from rival groups “already using similar technology.”

It is a race the Colombian military is also entering with its scramble to deploy devices that can disable drones before they can deliver their deadly cargo.

Drone busters

One recent success was the use of the Spanish-manufactured Crow counter-drone system at last year’s UN Biodiversity Conference, called COP 16, in Cali.

The system was activated to protect the zone where delegates and state officials from the 196 countries were hosted at a summit previously threatened by the EMC armed group.

The Crow jamming system “detected over 300 unmanned aerial systems and blocked 90 unauthorized drone activities,” according to the Colombian Air Force reports after the event.

The Air Force has units specialized in tactical use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, UAVs, and looking to Colombian companies to develop locally-manufactured military drones and anti-drone devices.

Meanwhile military commanders are claiming considerable success with imported jamming technology such as the handheld DroneBuster, which is no bigger than a tennis racket.

According to General Federico Mejía, in charge of the Cauca offensive last year, while drones were “complicating the military’s operations,” many attacks had been neutralized.

“Fortunately, they have not impacted on the humanity of any soldier,” he said.

Civilians under fire

If the military have technical means to protect themselves, civilians may not be so lucky.

Whereas some attacks in El Plateado appear targeted at civilian structures, other cases appear to be incidents of collateral damage, where armed groups were targeting police stations in urban areas or groups of soldiers where civilians were nearby.

And historical data shows consistently that civilians are disproportionately affected by explosive devices such as landmines, launched bombs, or remote controlled devices.

“Explosive devices in both rural and urban areas continue to leave an indelible mark on society,” said the International Committee of the Red Cross last year when presenting figures from 2023, which recorded 380 victims of landmines and controlled explosive devices, including 61 deaths. Of these 60 per cent were civilians.

Colombia has a long history of lethal mistakes from home-made armaments, such as an infamous incident in 2002 when a FARC cylinder bomb misfired and killed 80 civilians sheltering in a church.

And whereas drones might at first appear to be more accurate weapons, a key concern is that military jamming devices used to protect troops could instead cause these armaments to detonate on bystanders.

“Once disabled these things could crash and explode on impact. We have no way to stop them,” a community leader told Latin America Reports. He asked to remain anonymous.

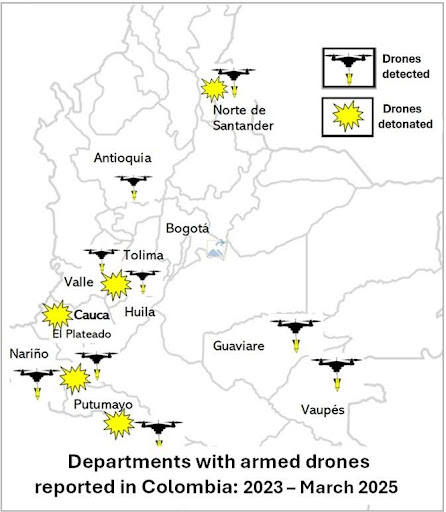

So far there is no specific data on civilian drone victims, though likely this category will be included in future reports. Our own analysis of information in the public domain reveals communities bombarded by drones in Cauca, Nariño, Valle de Cauca and Tolima.

Other at-risk departments, based on military finds of cached armaments, include Norte de Santander, Arauca, Huila, Guavaire, and Vaupes. All the signs are that drone warfare in Colombia – and its number of innocent victims – will reach new heights in 2025.

Featured image: A drone in Colombia carrying a simulated explosive charge, similar to those used by irregular armed groups. Image credit: Steve Hide