“We are just going to ask him some questions and we’ll bring him back in an hour. ‘Don’t worry, ma’am,’ he told me,” said Luz Edith Franco. This was 17 years ago.

Franco is talking about her husband, Arles Edison Guzmán, who was forcibly disappeared 17 years ago from Medellín’s Comuna 13 one month after Operation Orion: the 2002 Colombian military offensive to remove left-wing guerillas from the area. It has since been proven that military forces collaborated with right-wing paramilitary groups during the operation, and in 2017, the Inter-American Court of Rights condemned the Colombian state for its role in the human rights abuses committed.

Franco’s words are now visible for all of Medellín’s commuters and Metro users to see, as part of a recently-launched advertising campaign by Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP).

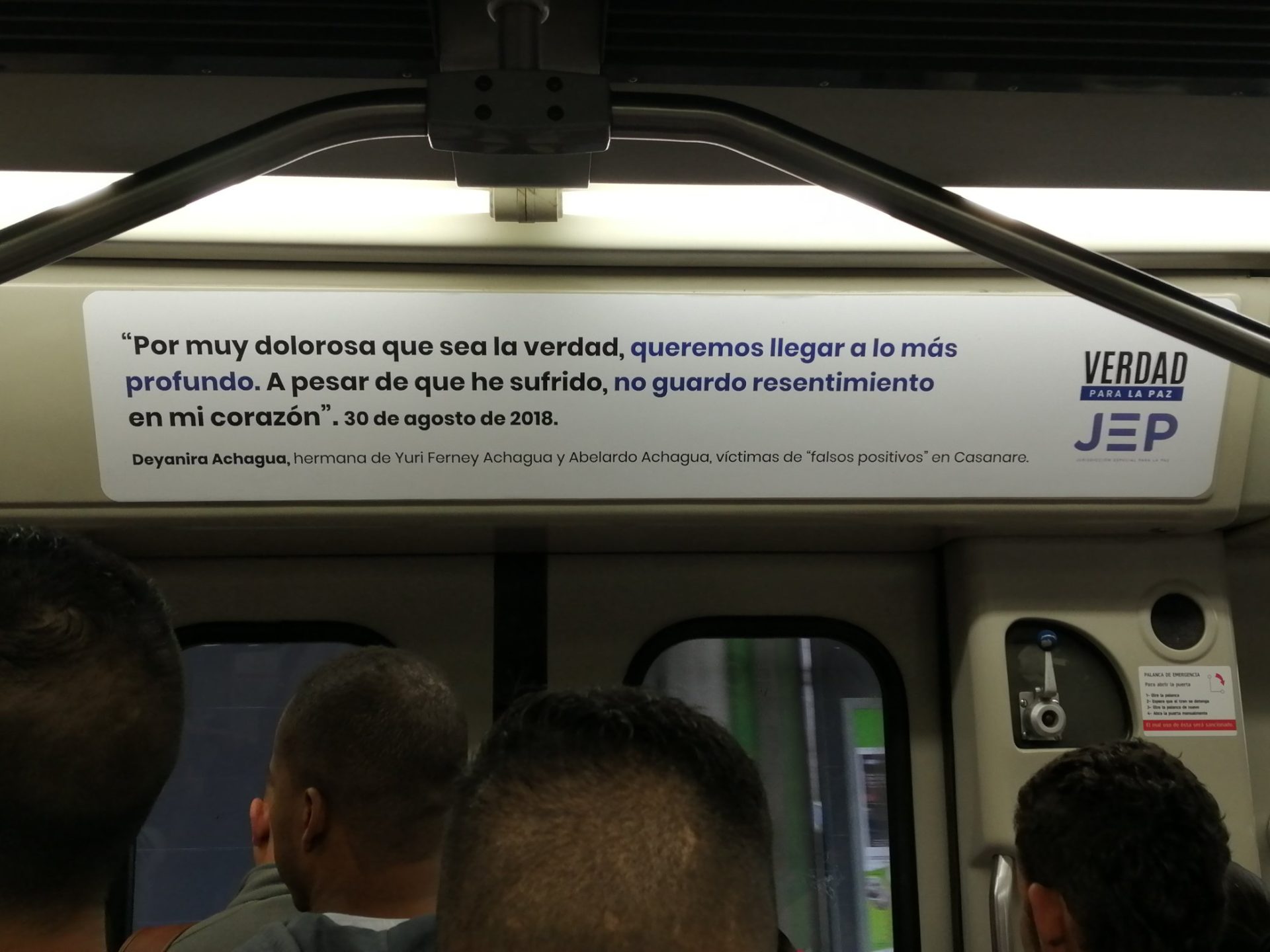

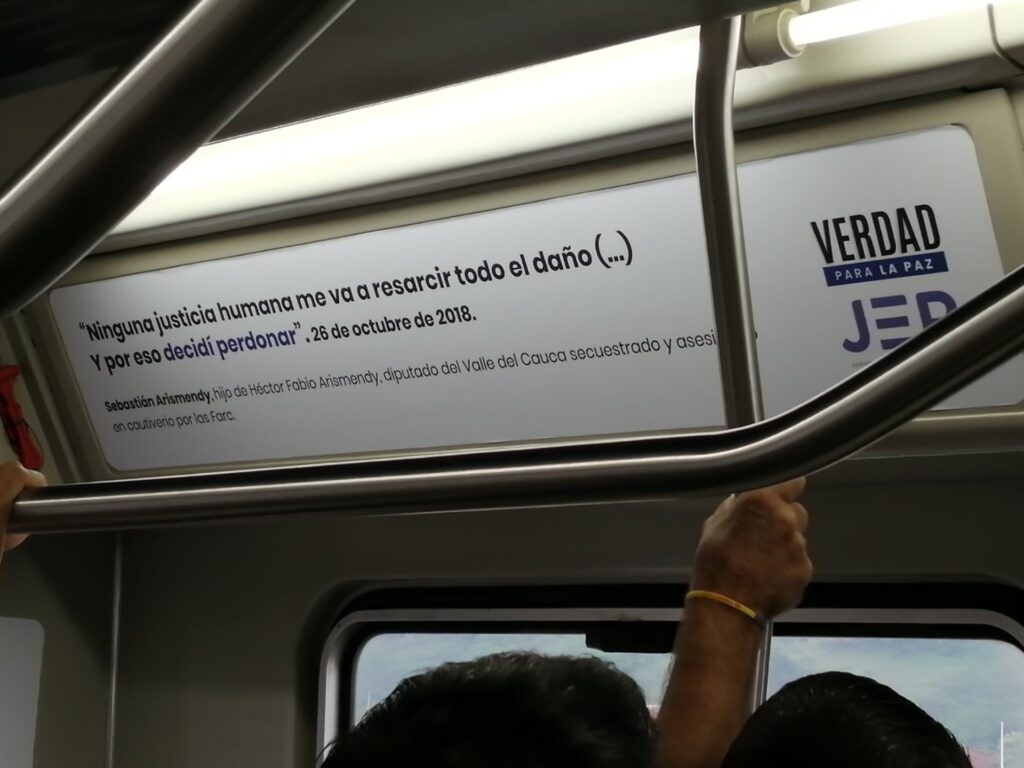

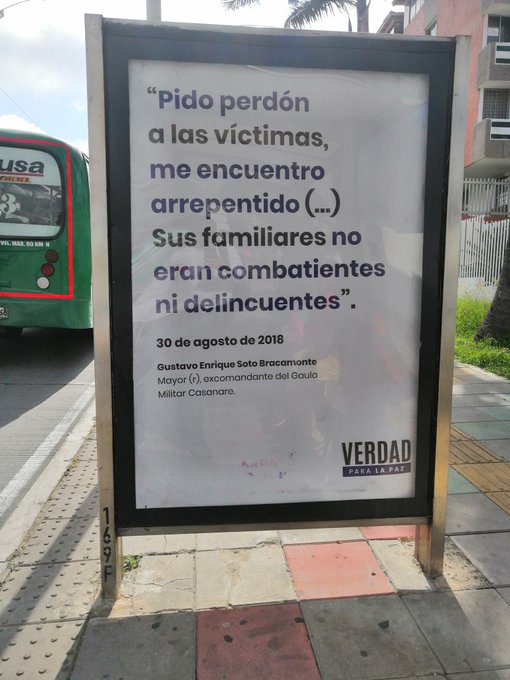

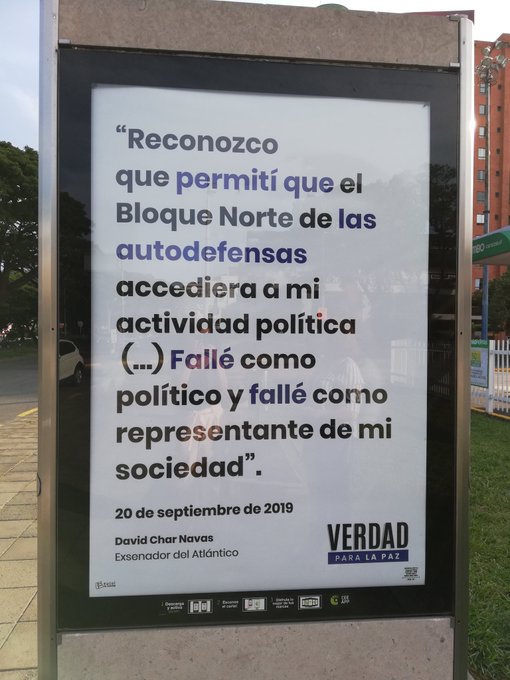

The recent campaign has plastered quotes from victims of Colombia’s armed conflict, as well as conflict-related phrases, figures and statistics all over the inside of Medellín’s metro carriages, as well as in and around some stations.

Barranquilla.

But Medellín is not the only Colombian city this campaign is targeting: advertisements can also be found in the main public transport networks of Bogotá, Bucaramanga, Cali and Barranquilla.

From Bogotá’s crowded Transmilenio bus network system, to Cali’s Mio and Medellín’s unique metro, the JEP chose to use public transport as a means of transmitting its message because it was simply the easiest way to reach as wide a variety of people as possible, a spokesperson from the institution told Latin American Reports.

“The goal of this campaign was to make Colombians aware of the truth,” the spokesperson said. “These phrases … are unavoidable, concrete facts,” they added, explaining that the distribution was intended to provide Colombians with the right to the truth — a right many have been historically denied — and not to promote the JEP’s work.

The JEP is a state-funded institution that was born out of requirements put in place by the 2016 peace agreement with FARC rebels. Its objective is to investigate and sanction some of the most serious crimes that occurred during Colombia’s armed conflict, beyond the borders of Colombia’s justice system. The JEP’s mission is also to provide the right to the truth for conflict victims and their families, with the ultimate goal of preventing similar events from happening again.

In a previous interview with Latin America Reports, however, Andrei Gómez-Suarez — a researcher in memory and reconciliation in Colombia — explained how Colombians’ knowledge of the JEP’s workings and faith in it as an institution was low. “The JEP has a deficit of legitimacy amongst Colombian civil society,” he said.

Cali.

The JEP’s most recent campaign, however, aims to make it impossible for people to be unaware of its mission.

“People read these phrases in the victims’ voices and they realize … that they are dignifying the fight of the victims, as well as their memory,” the JEP stated. “It’s a very emotional campaign.”

The campaign’s posters relate to phases of the armed conflict that are specific to each city they are displayed in, such as Operation Orion in Medellín. There are also messages that relate to the conflict on a national scale. Some quotes touch on themes such as forced disappearances and the ‘false positives’ scandal, in which the Colombian military carried out extra-judicial killings and dressed corpses in uniforms of left-wing guerrilla fighters to boost body counts quotas

Although government funding for the institution is decreasing, the JEP will further their recent public transport campaign to Colombian radio and social media. A lack of financial resources means that the institution is not yet able to look into other public spaces in which to run further advertising campaigns.