Renowned Colombian reporter Jineth Bedoya announced on this week that she will abandon her legal proceedings in Colombia against those presumably responsible for her May 25, 2000 kidnapping, gang rape and torture.

“Today I have made the most difficult decision since my kidnapping, 25 years ago: due to the inaction of the Prosecutor’s Office, I am irrevocably giving up my pursuit of justice in Colombia. The impunity of my case will remain as part of the country’s history. My work, through journalism, will continue,” Bedoya stated on X.

In a letter shared to Attorney General Luz Adriana Camargo and subsequently published on social media, the journalist noted that abandoning her legal struggle in her home country of Colombia is difficult, especially because she has dedicated half of her life to fighting against injustice and impunity.

“I have exhausted my humanity after years of systemic re-victimization, and today, 25 years later, my life remains threatened. My pursuit of justice is dead,” the letter read.

“The justice system in my country was neither diligent, nor capable of resolving a case that has been labeled ‘emblematic’, despite possessing all the evidence, testimonies and proceedings [required to do so]. I give up because I don’t want to keep mistakenly feeding the illusion that ‘something will happen someday’ and in the meantime continue to abandon my right to life,” Bedoya added.

The announcement comes nearly 11 years after the Prosecutor’s Office confirmed the case was a Crime Against Humanity, and following the Interamerican Court of Human Rights’ (IACHR) August 26, 2021 ruling, in which the Colombian State was found responsible for violating the journalist’s human rights.

Image Source: Jineth Bedoya via X.

The reparations mandated by the IACHR to be paid by the Colombian State for their responsibility include the continuation of investigations to determine and sanction those responsible for the violence against Bedoya, creating and implementing an education program on gender-based violence for public servants, and building a national memory center in honor of women victims of sexual violence and women journalists, among others.

So far, however, only three former paramilitaries have been tried in connection to the case: Alejandro Cárdenas Orozco, known under the nom de guerre “JJ”; Jesús Emiro Pereira Rivera, “Huevo de Pisca”; and Mario Jaimes Mejía, “El Panadero.” As reported by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), the men were sentenced to 45, 40, and 28 years in prison, respectively.

Image Source: Fundación Para la Libertad de Prensa via X.

Regardless, a Medellín court freed Pereira Rivera in 2021, and although police were instructed to re-capture him, the criminal has since remained a fugitive in what the Foundation to Protect Journalists deemed a “grave error” of Colombia’s justice system while in conversation with newspaper El Espectador.

May 25: A day for dignity

The violence against Bedoya did not start or end with the tragic events of May 25, 2000. As per the IACHR ruling, Bedoya was especially targeted for both her gender and profession in the context of Colombia’s internal armed conflict, which was also permeated by sexual abuse and “generalized impunity.”

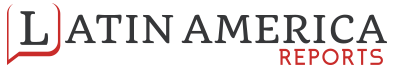

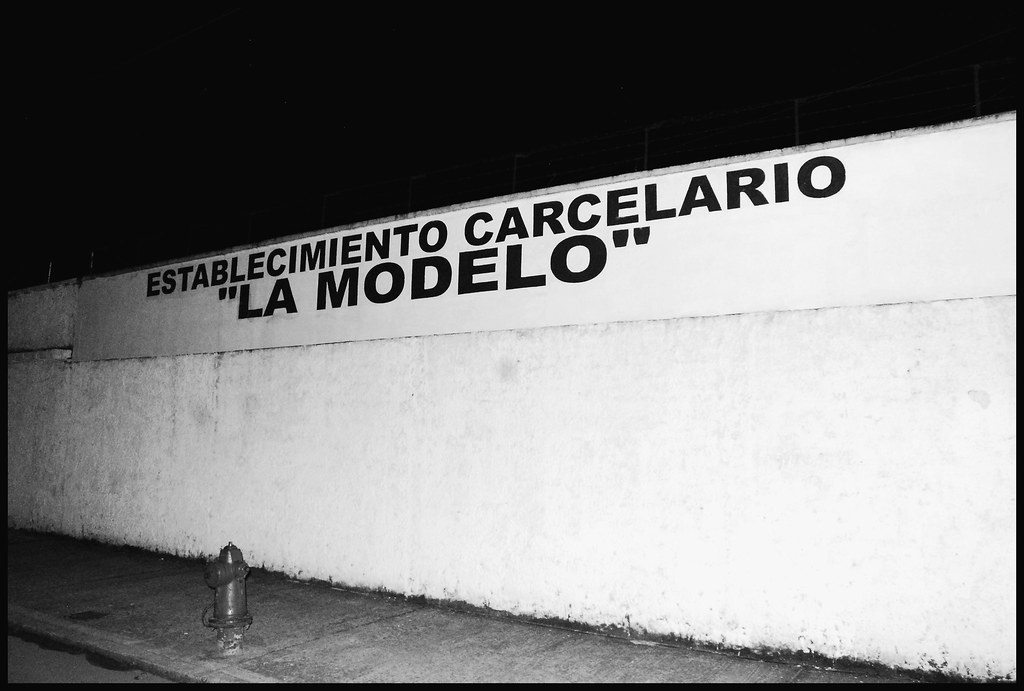

The journalist began her career in 1995, since then becoming the victim of constant threats. By 1998, Colombia was considered the “most deadly place for the press in the world,” the same year that Bedoya first began covering the country’s conflict and reporting on prisons, according to the ruling.

Namely, the journalist began covering the La Modelo prison in Bogotá, where the captured leaders of Colombia’s most violent armed groups were held.

Creative Commons Licenses

“What was unique about my investigation [in La Modelo] was that all of Colombia’s armed groups converged there; there were paramilitaries, guerrillas, members of drug trafficking mafias, and organized crime. Paradoxically, State agents who publicly fought these illegal groups were their allies inside the prison- they had agreements to traffic weapons and to supply arms to both FARC [guerrilla] fronts and paramilitary groups,” Bedoya noted in her March 15, 2021 testimony before the IACHR.

On May 27, 1999, Bedoya and her mother were attacked by two men, who tried to run them over with a motorcycle in the streets of Bogotá. In spite of reporting this to authorities, and in light of increasingly-violent threats, the police refused to provide the journalist with a security scheme, responding to her pleas in a November 1999 letter in which they deemed that her life was not at risk.

Bedoya continued her work in La Modelo, however. On April 27, 2000, paramilitaries and gang members clashed inside the prison, which resulted in the deaths of 32 inmates in what is known as the “La Modelo Massacre,” according to Colombia’s Truth Commission.

Bedoya was amongst the press team which thoroughly reported on the events. More specifically, the journalist investigated allegations regarding the role of paramilitaries in the massacre, as well as the alleged complicity of prison guards.

Consequently, Bedoya continued receiving death threats, presumably from paramilitaries who deemed her reporting as unfair and biased. After reporting it to the police, they assured her that the best way to prevent further aggressions was organizing an interview with the paramilitaries held at La Modelo, according to the IACHR.

The interview with paramilitary inmate “El Panadero” was thus scheduled for May 25, 2000, which Bedoya attended with her editor, a photographer, and a driver – the latter two waiting in the car for permission to enter. Upon arrival, a prison guard stalled the team saying their permits “were on their way,” and after editor Jorge Cardona left to get the photographer, Bedoya was kidnapped at gunpoint.

Image Source: Colombian Truth Commission

“The man dragged me by the elbow from the prison door, past a police patrol – which at the time provided security to La Modelo – and into a nearby storage building, where two men were waiting. They blindfolded and beat me, and then put me into a car, driving out of the city,” Bedoya testified.

The blindfolded journalist was then transported to the estate of paramilitary collaborator and emerald czar Víctor Carranza, where others, including “uniformed men” were waiting. After tying her up again, several men raped her, while insulting her work and stating that journalists were “paid by the guerrilla,” Bedoya told fellow journalist María Jimena Duzán in 2021.

Parallel to her kidnapping, Bedoya’s colleagues assumed that she had entered La Modelo, and waited for her at the gate. Cardona asked guards repeatedly if Bedoya had entered the prison, to which they responded by saying that they could not provide such information.

Image Source: Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia via X.

After several hours, the aggressors put her back in the vehicle, taped her ID to her chest, and threw her to the side of a road in the city of Villavicencio, over 100 kilometers south-east of Bogotá. In total, Bedoya was kidnapped for approximately 10 hours, during which she suffered verbal, physical, and sexual abuse.

The then-26-year-old reporter was subsequently rescued by a passing taxi driver and taken to a hospital, where personnel performed forensic medical exams. After a brief dispute between the military and police commanders, in which both entities wanted to transport her back to Bogotá, she was ultimately flown back to the Colombian capital city and admitted to a police clinic. Inside, Bedoya would testify, she felt unsafe with the police, as even during her rescue she suspected their complicity in her kidnapping.

The journalist was hospitalized for four days, and underwent several medical examinations, including a rape kit. From her hospital bed, Bedoya also denounced her kidnapping and abuse to police on May 26, 2000, filed under case 807 – the same case that came to an end in April of this year.

Among the many revictimizing actions from the Colombian State, Bedoya has signaled that a second rape kit was outrageously performed on the day following the kidnapping, that investigators “lost” the files of both examinations within government facilities, that she was forced to recount the harrowing experience over 12 times, and that the lead prosecutor in the case asked her to conduct her own investigations to identity those responsible. (It was Bedoya herself who identified Pereira Rivera as the second rapist).

During the process before the IACHR, first issued in 2011, the Colombian State argued that judges were biased, and removed themselves from the hearing.

“As one of the organizations representing the journalist, we consider that the State’s behavior demonstrates its neglect toward victims of sexual violence in armed conflict and negates them dignified spaces to access justice […] The State’s unprecedented withdrawal from the hearing is part of a broader strategy aimed at delegitimizing the Court and represents yet another obstacle in the process that continues to punish Jineth Bedoya for raising her voice,” the Center for Justice and International Law stated.

Regardless, then-President Juan Manuel Santos established May 25 as Colombia’s National Day for the Dignity of Victims of Sexual Violence in August 2014, honoring Bedoya’s fight for justice.

As per the Colombian Truth Commission, sexual violence is heavily underreported, although 32,446 cases have been documented before official authorities. However, the Casa de la Mujer women’s rights group reports that there were nearly 490,000 cases between 2001 and 2009.

It is estimated that women and girls comprise 92% of victims of sexual violence during Colombia’s still-ongoing armed struggle.

No Es Hora de Callar

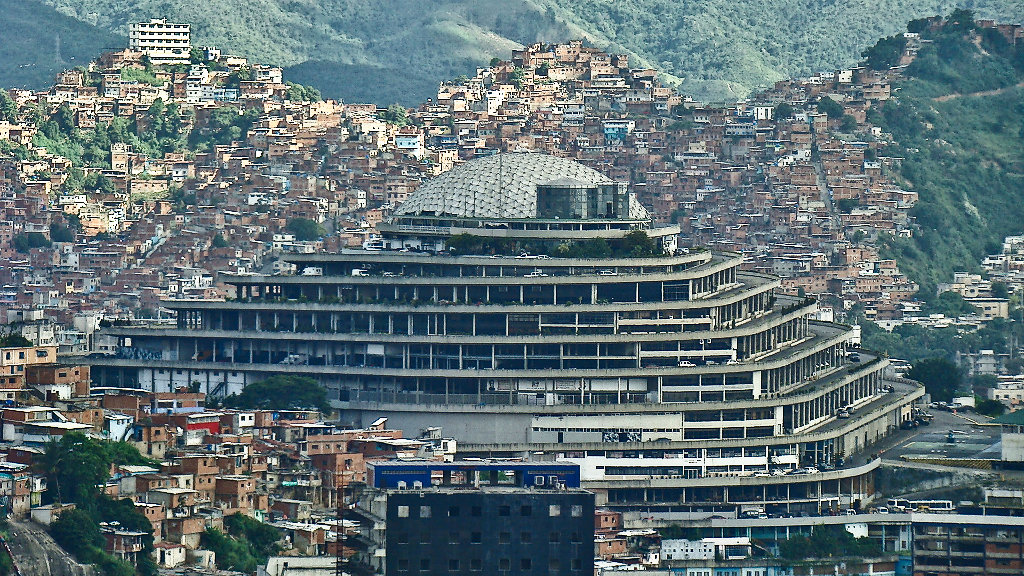

In 2009, Bedoya started a campaign titled No Es Hora de Callar (It’s Not Time to be Silent) in alliance with other women with similar stories of abuse. Through it, the journalist works to break the silence of sexual abuse and denounce events before State authorities.

Image Source: Jineth Bedoya via X.

The campaign has since worked with universities, newspapers, civil society organizations and government entities to shed light on cases of sexual abuse and the impunity that has traditionally accompanied them. In 2020, for instance, an investigation with Los Andes university in Bogotá found that six out of every 10 women journalists have experienced gender-based violence in the workplace, and that eight out of 10 self-censor to avoid being victims of violence.

More recently, No Es Hora de Callar partnered with the Ministry of Justice in May 2024 to paint a mural in the still-active La Modelo prison, in a message of resilience and strength to victims of sexual abuse. Additionally, the government announced the creation of the No Es Hora de Callar fund for the protection, prevention and assistance of women journalist victims of gender-based violence on September 9, 2024.

Image Source: UN Women Colombia

Since her kidnapping, Bedoya has also been celebrated with the International Women’s Media Foundation Courage in Journalism Award, the Committee to Protect Journalists Press Freedom Award, and the UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize. She has also continued her journalistic work through Colombian newspaper El Tiempo, where she is the editor of the Gender section.

Despite her efforts, however, Bedoya is convinced that her case will remain in impunity. Nonetheless, she remains committed to journalism and her fight against gender-based violence.

“To all victims, I want to make something clear, despite my tragedy: it is always worth fighting. The meaning of justice is as fleeting as it is vast, and not everyone will endure the painful experience of impunity. My justice today is leaving a legacy for women journalists and for the women of my country […] Even if tomorrow I no longer breathe, the task is done, because I opened the door for Colombia to start talking about sexual violence against women and girls. That is my tangible justice,” Bedoya’s April 28 letter concluded.

Featured image credit:

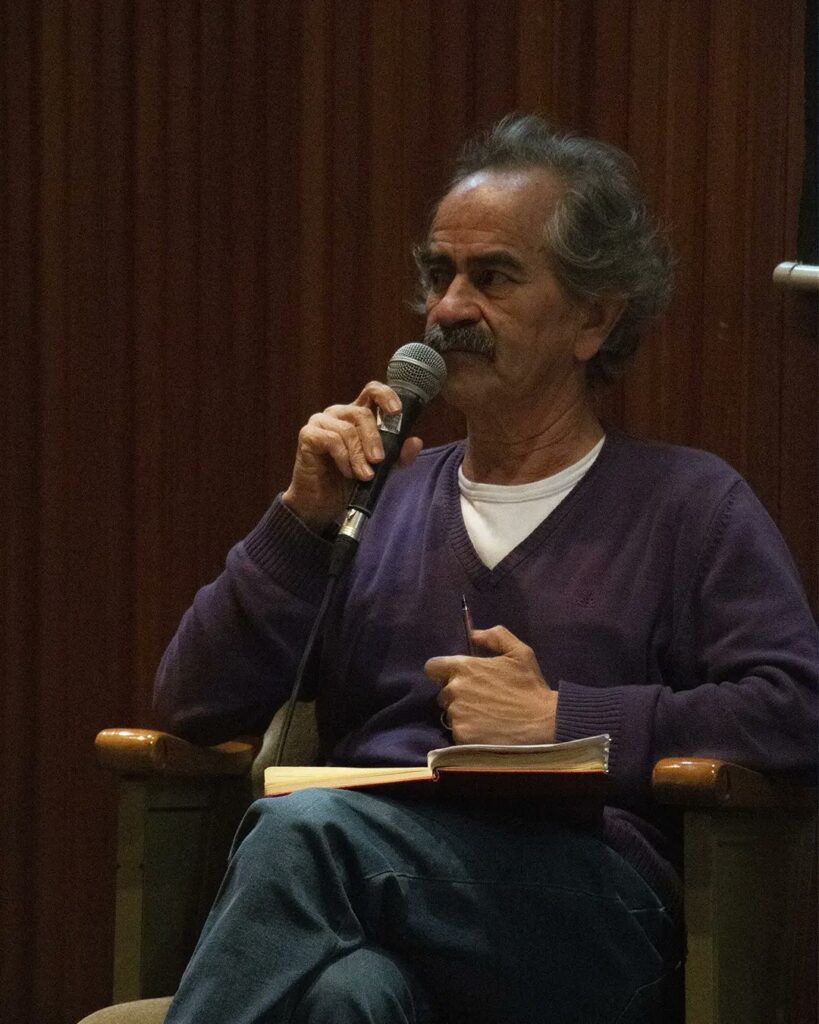

Image: Jineth Bedoya in 2015

Photographer: Daniel Clima via Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (Flickr)

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/cidh/22362677106

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/