The Colombian night monkey can be distinguished by its large, closely-set eyes. It is small, about the size of a squirrel, and is the only nocturnal primate in the Amazon rainforest. It is also severely threatened by illegal wildlife trafficking.

These monkeys are also conservationist Angela Maldonado’s passion. Dr. Maldonado, who is the scientific director and founder of NGO Fundación Entropika, has dedicated her career to their conservation in the Amazon rainforest since 1998: an endeavor that has since put her life at risk.

Her team’s fight to conserve the species has brought them into contact with different sectors that rely on the illegal trafficking of night monkeys for their own commercial interests.

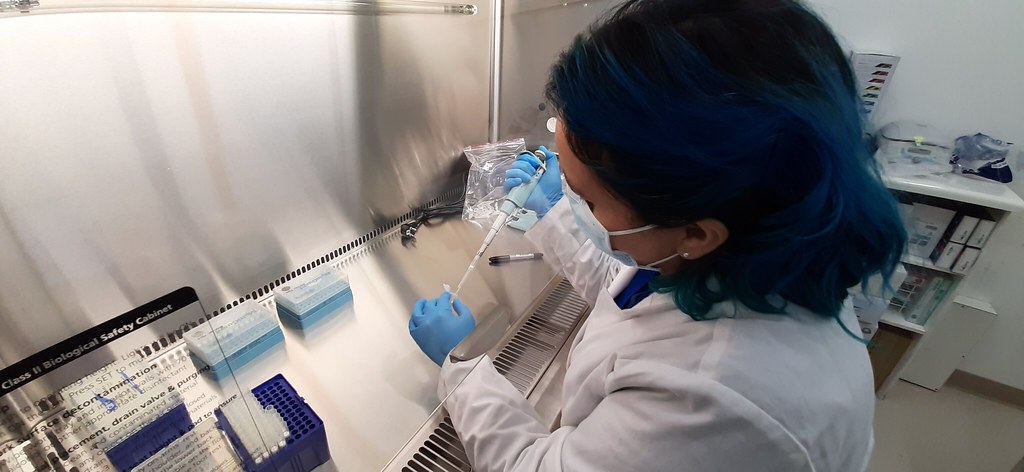

These primarily comprise of medical research associations such as the FIDIC, which uses the endangered species for biomedical laboratory research into diseases such as malaria and tourism companies that promise sightings of the rare animal to their customers looking for the perfect photo opportunity.

However, these sectors do not carry out the animal trafficking itself. They subcontract this job to local indigenous communities — such as the Cocama, Tikuna, and Yagua peoples — who do this labor for them.

“The indigenous person is no longer the person we have a romanticized image of in our heads, the one who protects the land and its resources,” Maldonado told Latin America Reports. “Indigenous communities are losing their culture,” she added.

However, she argues, the participation of local indigenous communities in criminal activities such as the illegal wildlife trade is by no means any fault of their own, but often a last resort they are forced to turn to as a means of earning money.

“There is clear evidence that they do not have access to basic necessities,” Maldonado said, highlighting a lack of healthcare, education, drinking water and general low standard of living.

READ MORE: Brazil’s indigenous people are best positioned to protect the Amazon

It was early on in her conservation career that she realized taking on the Colombian state’s role of providing access to these basic human rights was the first step to tackling illegal industries such as wildlife trafficking.

“Conservation cannot exist alongside hunger,” she said.

So, alongside Entropika’s mission to return the trafficked species back to its natural habitat, Maldonado and her team also run community-based activities — such as providing education, drinking water and sustainable tourism initiatives — in a bid to achieve social and economic transformation. In the long-term, they hope to create an environment in which vulnerable indigenous communities will not feel the financial need to resort to illegal wildlife trafficking.

However, in August this year, the team at Entropika received an email death threat for its work in the small Peruvian town of Puerto Alegría, a short boat trip from the Colombian NGO’s base in Leticia, Amazonas.

Tourist agencies promising their clients photo opportunities with wild animals — including night monkeys — were paying local indigenous communities to illegally traffic the endangered species into Puerto Alegría, Maldonaldo claimed. In response, Entropika participated in an operation headed by Peruvian authorities in December 2018 to return them to their original habitat, and has since been working on establishing a sustainable tourism association in the town.

The death threat — which came from the tourism agencies whose finances had been dented by Entropika’s work in the town — didn’t surprise Maldonado, whose team has previously been subjected to smear campaigns and intimidation by other entities. “When you start messing with people’s pockets and reputations and revealing unwanted evidence… obviously those sorts of people are used to killing whoever gets involved, and then the threats start to arrive,” she said.

“Here, people got used to making easy money,” Maldonado said, explaining how a chain of criminal activity — involving the trafficking of animals as well as the production and sale of illegal narcotics — operates in the region of Leticia, which is strategically positioned on the triple border between Colombia, Brazil and Peru. This chain, she claims, involves actors from indigenous groups, to commercial enterprises, local politicians and even the local environmental authority, Corpoamazonia.

While Colombia’s National Protection Unit (UNP) continues to process Maldonado’s case, she has been ordered to relocate immediately.

“It’s annoying because [I am] the person doing the right thing,” she commented, frustrated at being forced to leave her region of work for doing a job that she believes is the responsibility of the Colombian government. “Why am I the one who has to leave the area because of that?” she asked.

Maldonaldo’s work with indigenous communities — which lead to the death threat — is a direct response to state neglect of the region. But if this wasn’t enough, the protection measures the state offers to protect her while she works are also insufficient, she believes.

“The methods the Colombian state is using to protect social and environmental leaders… well, the evidence shows that they are not working,” she claimed.

READ MORE: What is the government’s current commitment to protecting social leaders in Colombia?

The maximum protection measures Maldonado expects to receive following the death threat will be a bulletproof vest and a panic button.