The number of migrants intercepted at the United States’ southern border is on the rise. In May, the latest month with published data, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) recorded its highest monthly total in more than 20 years of over 180,000 migrants, mostly single adults. Economic precariousness, government corruption, crime, violence, and climate change are all driving migration from Latin and Central American countries. And it is showing no signs of stopping.

Border activist, journalist, and minister Rev. Dr. Robin Hoover has over 30 years of experience in human rights work, the US/Mexico border, and migration. Hoover has founded several nonprofit organizations including Humane Borders, Inc. a social welfare organization dedicated to reducing migrant deaths and advocating for changes in migration policy that place migrants at risk. He is currently working on a project called Proyecto Rescatame! that uses satellite-based technology rescue beacons to rescue immigrants on their arduous and often deadly journey. Hoover has been known to leave water for migrants in the Sonora desert along well-traveled routes.

Hoover is based in Tucson, Arizona which gives him access to the border and to detention and correctional centers in Nogales, AZ under the Department of Homeland Security including one center, which made international news for overcrowding of facilities holding unaccompanied minors. Latin America Reports spoke with him about his experiences in detention centers, implementation of U.S. immigration policy, and his predictions surrounding the future of immigration.

What happens in a migrant detention center?

The United States government maintains the world’s largest immigration detention system. According to the Detention Watch Network, the 2019 average daily population (ADP) in detention was 50,165 and the number of people detained for the year 510,854. The U.S. government spends more on federal immigration enforcement than on all other principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies combined, and has allocated nearly $187 billion for immigration enforcement since 1986.

Detention centers have many roles: from simply acting as a processing center to functioning as a longer term jail cell. Because of the stigma, some detention centers change their name to “processing center” but their scope and application remain the same. In many cases, immigrants are not even detained for long. Some are simply sent right back. “Some are kept for hours, some for days,” says Hoover. “Then they might separate the wife from the husband and the wife goes to Tijuana and the husband to El Paso.”

If during processing a migrant is found to have an aggravated felony or a DUI or to have attempted multiple illegal crossings (termed recidivism) they are then open to prosecution under U.S. law. “It can be a long time before your case even comes up,” Hoover says. “If you’re a migrant you’re just screwed. You may think ‘I am going to the port of entry in McAllen, Texas.’ And daddy goes this way, mom goes this way, and the child goes another. And they don’t see each other again.”

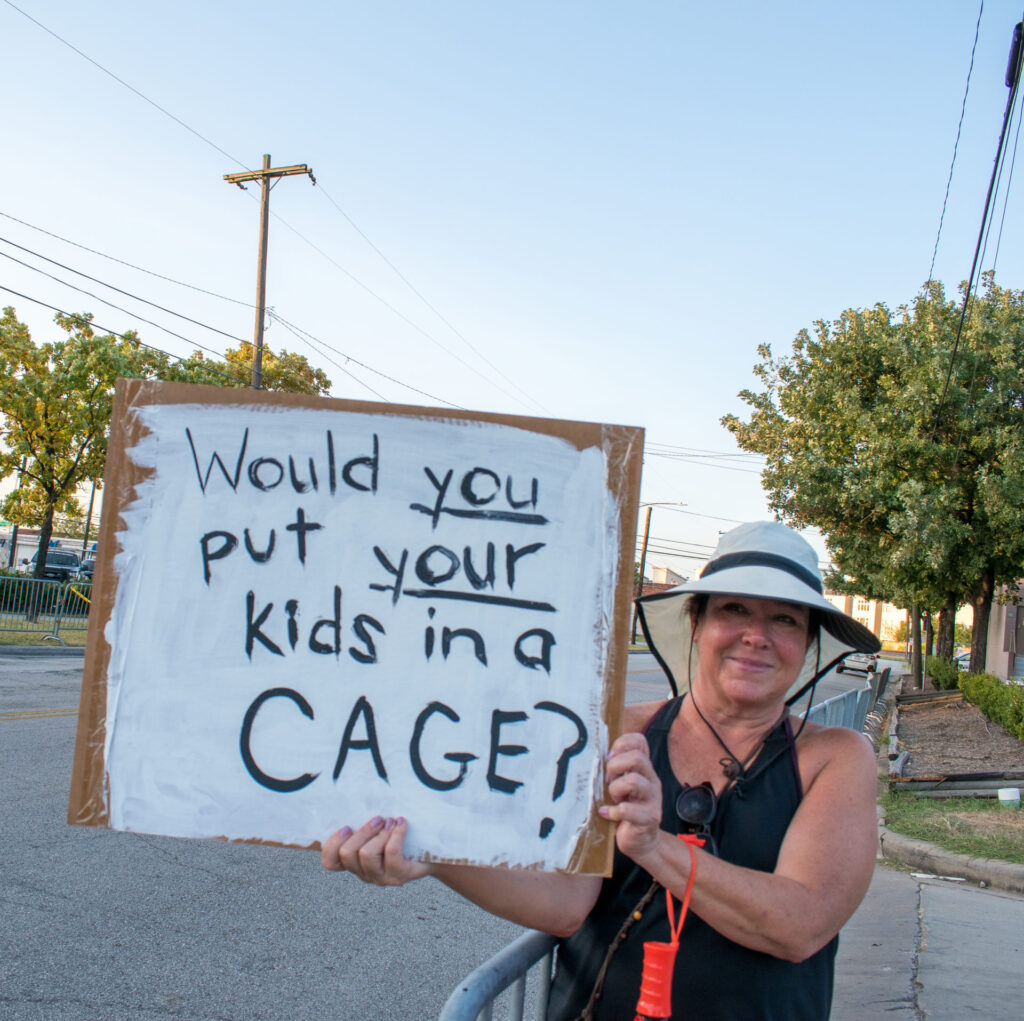

What about kids in detention?

Children are treated separately from parents and adult migrants. The 1997 Flores Agreement strictly limits the government’s ability to keep unaccompanied minors in immigration detention. Children can only be in detention for 72 hours and are permitted to be released to a guardian or other responsible adult in the U.S. (not just their birth parents). However, the Flores Agreement has been modified, abused, and even ignored.

Under the administration of former President Donald Trump, the Flores Agreement was used as an excuse to separate children. The administration stated that because it could not keep parents and children in immigration detention together, it had no choice but to detain parents in immigration detention and send the children to the Department of Health and Human Services. Additionally, terminology is of the essence. As of 2019, the stipulations of the Flores Agreement apply to an unaccompanied alien child (UAC), not unaccompanied minors. “UACs warrant special protections because of the absence of parental supervision, while the treatment of accompanied minors must balance their welfare with the orderly enforcement of U.S. immigration law,” according to Lawfare.

And there are more hoops. In 2020, the CDC deployed a medical quarantine authorization that allows for any migrant or migrant child to be sent back to their home country simply based on COVID-19 transmission risks. This authorization overrides the protections of immigration and refugee laws through the use of an unreviewable Border Patrol health “expulsion” mechanism.

“Back in 1986 when I first visited a detention center in Texas it was called Los Fresnos Education Center and had fewer than 100 minors there. At the time there were only 500 minors in the entire United States. Now it is called Port Isabel Service Processing Center. There are probably four or five thousand kids in detention in that same county today,” Hoover says. “Twenty-five years ago it was like a group home. No fences, windows, healthcare, and social workers, clergy and educators could come in and out. Today it is concertina wire and cameras and armed guards. It’s changed dramatically. It is much more of a prison industry today.”

Asylum is limited

“Coming here legally is almost nonexistent for many countries. The U.S. may only admit twenty thousand people by political asylum in an entire year in the entire world,” says Hoover. Refugees are people who have fled war, violence, conflict or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety in another country and must be vetted while still overseas and approved for entry to the United States. The number of refugees accepted to the United States each year is set by the sitting president in consultation with Congress. Asylum seekers are in a different category because they arrive at a U.S. border or port of entry and then request asylum. In both cases there are caps on the amount of visas issued and processing times can take months to years. If there is one thing a fleeing migrant doesn’t have, it’s time.

There is a per-country limit on the number of visas that can be issued because the U.S. does not want to have an inordinate amount of immigrants coming from any one particular country. “Technically speaking, just applying for a visa doesn’t exist,” says Hoover. “Mexico might have 4,000 slots available. If you’re coming from a populous country the chances of having those spots available to you are almost impossible. And very rarely does the U.S. admit how many are in the quota.” Winning the quota lottery is often too slim a chance for a migrant fleeing violence and instability. Risking an illegal border entry is often the only viable option.

Administrations and migration

Each administration has had different approaches to illegal immigration and also different areas of focus. Some have targeted quotas, others illegal immigrants within the U.S., and others deportation, with democrats often taking the lead on the most sweeping deportations and strictest immigration policies. Or in Hoover’s words: “It changes every damn day.”

President Bill Clinton implemented some of the harshest policies. The bills he passed expanded the grounds of deportation to include not only serious crimes, but nearly any crime (including misdemeanors). It also required that many of the immigrants facing exile for a crime be imprisoned indefinitely, beyond the period of their sentence, until that exile could occur and permitted fast deportations in which officers could expel immigrants without any hearing from a judge. “Children were being hurt, abused, and mistreated under Clinton,” Hoover says. Contrary to popular belief, President Obama deported the most migrants during his two terms.

Hoover has worked on either side of the Texas and Arizona borders with Mexico through seven administrations. However, the Trump Administration and its sweeping family separation was the only one Hoover describes as abjectly cruel. “He encouraged the abusive cult of ICE and championed mistreatment of migrants,” he tells Latin America Reports. “He didn’t deport, he detained, and then he instituted the family separation policies. There has always been the policy option for prosecutors to separate children from their parents. Trump came along and made it extensive. It wasn’t a matter of policy. It was a matter of implementation. And it was sending a message: don’t bring your kids here.”

What about now?

On the campaign trail, Joe Biden vowed to reform U.S. immigration and to “take urgent action” to undo the policies of former president Donald Trump. But since the Democrat took office, the reality for migrants has not changed dramatically. Since January 2021, Biden has created a taskforce to reunify migrant children with their families and terminated construction contracts for some portions of the border wall. Biden intended to keep the Trump-era limit of refugees entering the U.S. to 15,000 annually, the lowest it has been since the passage of the Refugee Act of 1980, but after massive backlash he raised the cap to 62,500.

Additionally, the Biden administration has opted to continue to implement the public health rule that has allowed it to turn away hundreds of thousands of migrants in place this past month. As of March 20, 2020, all new asylum seekers have been denied access to the asylum process and are being immediately returned to either Mexico or their country of origin. In what has been labeled a huge step backward from his campaign promises, Biden has come under scrutiny for his reactivation of Trump-era facilities that hold up to 700 migrant children. From the “tent city” in Tornillo, Texas, to a sprawling for-profit facility in Homestead, Florida, emergency shelters have been criticized for their conditions and cost, as well as a lack of transparency in their operations. So far, President Biden has reunited thirty-six families out of hundreds.

In a perfect world

How would Hoover like to see the United States better handle migration? He says the solutions are much easier than one might think. He outlined two alternatives that would result in more compliance and a lot less ICE agents on the loose

First, Hoover proposes that all undocumented people living in the United States be given a temporary visa. “We should say ‘Okay you’re here. And you’ve got these years to work, rent a property, drink beer, eat pizza and do whatever it is that you want to do. When the visa is up, you go home. And if you want to become a citizen you can apply during that time.’”

Second, for individuals who want to come and work for a while and send money home there would be a process where they could be background checked and vaccinated in their home country. Once they are cleared they could work in the U.S. but the money they earned would go into an account for their family they are supporting back home. “Fly home and take care of mama and then fly back. Until your visa expires.”

“This creates legal work opportunities,” Hoover adds. “We need to think about that in the grand scheme of things.”

The future

The share of the population willing to migrate permanently in the world is highest in Africa and Latin America. In addition, the willingness to migrate is highest among youth who are more inclined to migrate permanently than adults.

Migration is here to stay. And without legal, safe options it will continue despite all the laws against it and borders around it. Hoover and countless other individuals and human rights groups work tirelessly to smooth the way for migrants, in the hopes that the future is more empathetic and more prepared.