Given the recent nature of Colombia’s armed conflict, the country’s approach to historical memory is distinct from that of the rest of Latin America. Particularly in the city of Medellín, there is still pain, taboo and embarrassment around discussions of the subject.

Just last month, Medellín’s Monaco Building was demolished in a controlled explosion, reducing the eight-story building to rubble. The luxury block of apartments was built by drug-lord Pablo Escobar at the beginning of the 1980s as a home for him and his family. The area in front of the building was also the site of Colombia’s first car bomb explosion in January 1988, planted by the Cali Cartel. Up until its demolition, the Monaco Building had also become a reference point in several of the city’s ‘narco tours,’ marketed to tourists.

In Latin America, what to do with the physical reminders of where violence has occurred is a question as old as the region itself. Its past is littered with dictatorships, coups, guerilla warfare, and the collateral damage which are the dead, disappeared, tortured, and traumatised.

In Argentina, for example, the Buenos Aires Naval Mechanics School was the torture site of an estimated 5,000 people throughout the late 1970s and early 80s. Likewise, Chile’s National Stadium was used to hold political prisoners during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, some of whom were murdered. Rio de Janeiro’s Department of Political and Social Order (DOPS), where prisoners were tortured is also a stark reminder of Brazil’s military dictatorship.

Unlike the Monaco, these buildings have been preserved and many have been transformed into museums to honour the memory of the victims who suffered, or died, within their walls.

“These buildings in Argentina and Brazil are where the victims suffered…the big difference is that the Monaco represented the residence of the aggressor, and for this exact reason it is not the place where victims feel represented,” Casa de la Memoria museum director Cathalina Sánchez Escobar told Latin America Reports.

So, based on neighbours’ discomfort at the building’s role as a tourist hotspot, as well as its symbolism of Medellín’s most violent years, the decision was made to demolish it.

Vea la implosión del Edificio Mónaco desde el aire. #FinDelMónaco

Cortesía @Telemedellin pic.twitter.com/uaaBCWT3eS

— El Colombiano (@elcolombiano) 22 February 2019

The implosion of Edificio Monaco was the first stage of the local government campaign ‘Medellín embraces its history’ led by the city’s mayor, Federico Gutiérrez. With the help of almost 30 public and private entities – including the city’s Casa de la Memoria museum – the objective of this campaign is to tell the story of Medellin’s most violent years through the voices of the victims, explained director Sánchez Escobar.

The first and, so far, only fixed part of the campaign is the construction of ‘Parque Inflexión Memorial Medellín,’ a public park which will be built on the 5000m² of land where the Monaco Building once stood. Building work will begin this May and is expected to finish in November.

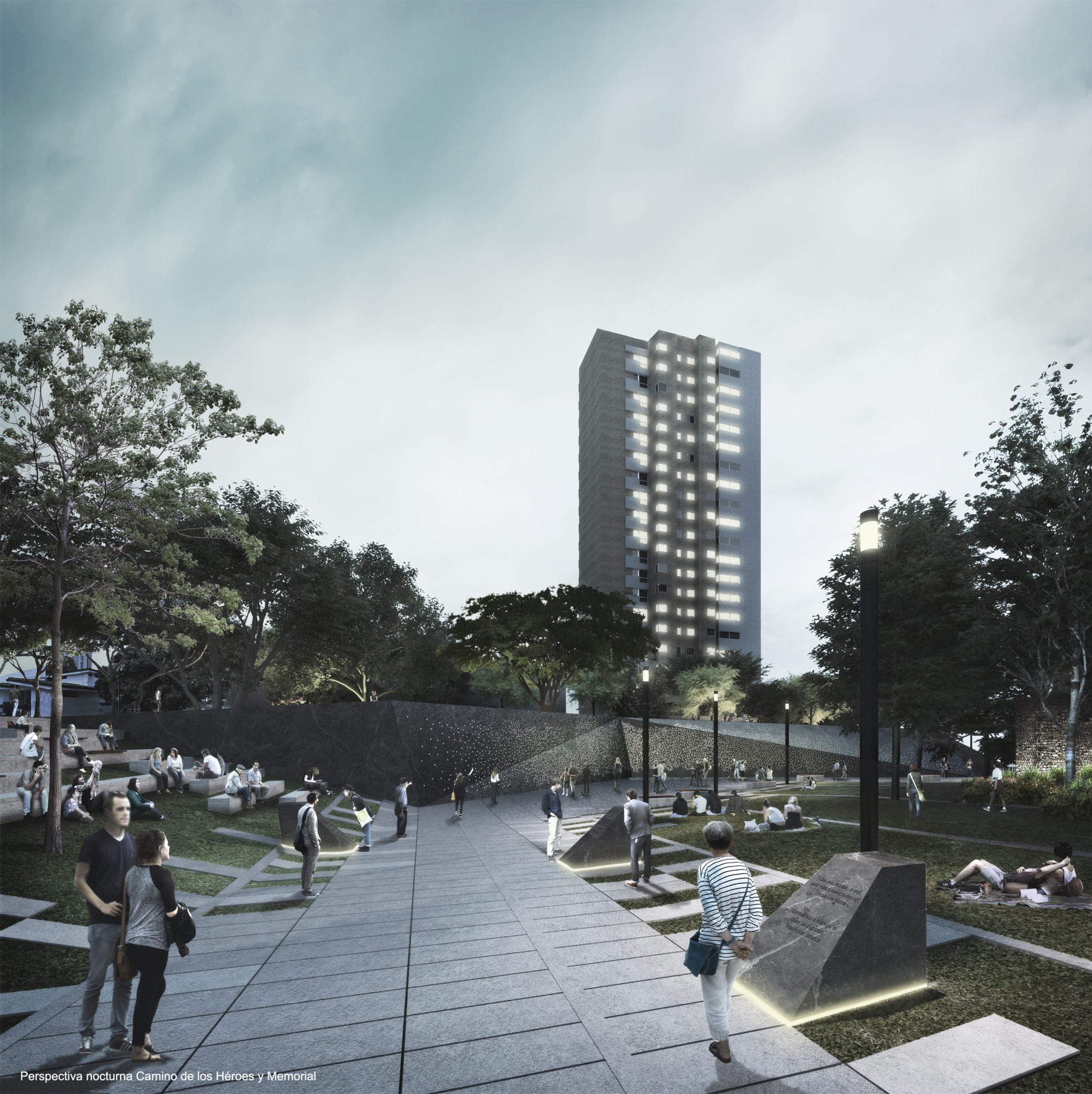

Speaking to Latin America Reports, one of the four architects who designed the memorial park, Tomás del Gallego described his team’s plans to compose it of three ‘moments.’

Image courtesy of INFLEXIÓN Parque Memorial Medellín.

The first moment, ‘The Essence,’ will be a descending walkway named ‘heroes walk,’ featuring monoliths that name those activists and human rights defenders killed in the city’s violence. The second, which he describes as “the most important” will be a wall called ‘Inflexión’ with 46,612 perforations to represent each of the victims that lost their lives over the period 1983-94.

“The idea with the wall is that people take ownership of it… they can bring little messages or flowers to fill the holes and feel closer to the victims,” he said.

The third moment, ‘The Forest of Resilience,’ will bring green space to the park in celebration of the victims’ lives. This quiet space will be reserved for reflecting on the city’s ability to move forward.

But instead of considering the complexities of how to move forward, discourse on the matter has centered more on whether or not demolishing the Monaco Building and replacing it with a park was the best use of the space.

Memorial park architect Del Gallego sees the decision as positive. “It’s a space that the city gains,” he said. “We still lack a lot of public space.”

El Espectador columnist and journalism professor Reinaldo Spitaletta, on the other hand, described the decision to construct a park as “unilateral” and “bureaucratic.” “Many sectors of society were not consulted,” he told Latin America Reports, “NGOs, universities, historians, teachers, for example.”

“There were faults… some sort of authoritarianism in the face of a decision in which the people did not participate… it was not democratised,” he said.

As one of the minds behind the ‘Medellín embraces its history’ campaign, Casa de la Memoria’s Sánchez Escobar insists that the focus should look beyond the decision and instead at the local government’ strategy behind it.

Although plans are not fixed, the government campaign also proposes the introduction of peace lectures into the educational system, as well as content for history classes focused on the city’s past. Designing an official ‘memory tour’ for Medellín is another of the project’s proposals.

Journalist Spitaletta also has similar ideas. “Whether it be inside or around these buildings, we need to incorporate aspects that relate to education, culture, history. So that this motionless thing – be it a park or a building – doesn’t just sit there, it needs to be dynamic and there need to be methods in place for people to approach it,” he said.

In short, a physical space alone cannot be the bridge for healing. In order to move forward in a country where traces of its armed conflict are still either raw or present, a unique approach to memory work must be taken.