A red cross on a white background is a universal symbol of humanitarian aid, whether it be emblazoned on the side of helicopters rescuing people from a natural disaster or identifying deliveries of food and water for those in need. However, the ICRC logo has been notably absent from the epicenter of the most reported-on crisis in the Americas–the border of Venezuela.

Earlier this month, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) openly condemned aid packages sent by the United States Agency of International Development (USAID) that have been dumped unceremoniously on the Colombian border with Venezuela, stating that they are being used as a political tool.

“At the present moment our concern and focus is really on the one side to increase our response to Venezuelans,” ICRC President Peter Maurer said to Reuters. “The other [concern is] to keep away from the political controversy and political divisions which are characteristic to the crisis in Venezuela.”

This does not mean that the ICRC has washed its hands of Venezuela. It is still working with the national Venezuelan Red Cross in hospitals and health programmes across the country, and at the beginning of February, doubled its resources to continue this work.

The aid operation is in accordance with Maduro’s government, but the ICRC is not seeking to take sides between Maduro and his political opponent Juan Guaidó, who declared himself interim president last month after claiming the illegitimacy of the current presidency.

In a bid to undermine Maduro, both Guaidó and US President Donald Trump are attempting to deliver USAID packages across the Colombian border in the face of Maduro’s point-blank refusal, who asserts that Venezuela is not “a beggar nation.”

The aid packages, purported to be worth around $20 million dollars, include food and basic hygiene packages to help struggling Venezuelan citizens, according to the USAID website.

The USAID has been criticised for being a front for US intervention in Venezuela, and getting the aid past Maduro’s blockade has even spurred conversations of military intervention, something that Trump declared was “an option,” according to The Guardian.

This stand-off is expected to come to a head on Saturday, February 23, when Trump and Guiadó are hoping to deliver the aid packages into Venezuela. This will take place after two head-to-head concerts taking place on Friday 22, one organised by Richard Branson on the Colombian side of the border, and the other in Venezuela, planned by Maduro with the tagline “Hands Off Venezuela.”

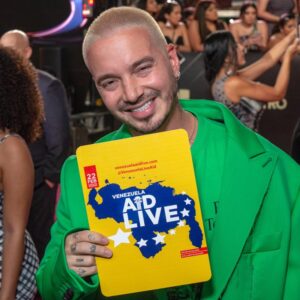

Colombian singer J. Balvin holds a poster for Venezuela Aid. Photo courtesy of Twitter @VenezuelaAid

This has raised the question of the role of humanitarian aid, what it represents, and to what extent it can really call itself free from political bias.

The objective of humanitarian aid according to the ICRC is, “to save lives, alleviate suffering, and protect human dignity, both during, and in the aftermath of man-made crises and natural disasters. Humanitarian interventions also work to reduce risks and strengthen preparedness to lessen the impacts disasters when they arise.”

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) add that all of their activities are guided by the four humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence.

However, there have been cases where politics have interfered with the delivery of aid, such as the UN’s severe delay in intervention during the Rwandan genocide. In a meeting to mark the the twentieth anniversary of the tragedy, the presidency of the UN Security Council during this time, Colin Keating, apologised for “the cascade of tragedy” that occured due to “a failure of political will.” Despite intelligence that a genocide was on the horizon, the entity chose not to intervene and 800,000 people were slaughtered in 1994.

During a commemoration ceremony 20 years later, the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon even admitted that “the shame still clings” to the international aid organisation, according to the BBC.

Therefore, it may be necessary for humanitarian aid to be open to a more politicised approach, suggested founding director of the Science Media Centre, Fiona Fox in a presentation on a “New Humanitarianism” in a 2001 Overseas Development Institute meeting. This new version [of humanitarianism] is not afraid to be political, Fox explained, and works on two main principles: defending human rights and supporting developmental relief.

Red Cross worker carrying supplies. Photo courtesy of Facebook, ICRC

The idea of developmental relief as a tool to not only provide aid for victims but also to create political stability is also becoming more accepted, even if it means using the withholding of aid as a strategic tool. A key example is UNICEF’s withdrawal of education assistance in the face of the closure of girls schools by the Taliban in 1996.

However, this “New Humanitarianism” does not comply with the UN’s or the ICRC’s – two of the largest international aid organisations – neutral and apolitical definition of humanitarian aid. In contrast, the packages sent by USAID to Venezuela are clearly being used as a political tool in order to weaken Maduro’s hold on the Venezuelan presidency.

The current attempts to deliver aid to Venezuela have highlighted these two contrasting definitions of humanitarian aid. Maduro has blockaded all main roads from Colombia to Venezuela to prevent the entry of aid, and recent reports from the BBC that the president has closed the country’s border with Brazil shows with clarity the power of politicised aid.