What remains of last week’s Venezuela-focused media storm are two leaders who both claim legitimacy, halted aid for those who need it most, and increasingly dire humanitarian and migration crises.

According to the latest figures from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) published this January, there are now approximately 3.4 million refugees and migrants that have left Venezuela for other parts of the world.

Following the failed “avalanche” delivery of humanitarian aid into Venezuela, two rival fundraising concerts, and multiple deaths and injuries caused by border protests; a step-back from the situation encourages us to question what has concretely been resolved.

The answer, quite simply, is not a significant amount.

Although the official checkpoints remain closed, migrants continue to flow across Venezuela’s land borders with Colombia and Brazil, as well as its disputed and seldom reported-on frontier with Guyana.

However, beyond barriers, police control and long queues of people, the reality of their journeys seems to have been lost amidst recent political upheaval.

COLOMBIA

Take the Venezuelan border with Colombia, for example. At 2,219 km long, there are seven official crossing points spread across four different departments of Colombia.

Starting in the northern La Guajira desert, migrants can cross from the Venezuelan town of Maracaibo to Colombia town of Maicao by land. The most used crossing points, however, are located in the Colombian department of North Santander, where four bridges connect the Venezuelan town of San Antonio del Táchira with Villa del Rosario, Cúcuta, via the Táchira River.

Puente Internacional Simón Bolívar, the 300 metre-long bridge that can be crossed exclusively by pedestrians during the day and vehicles at night, receives the heaviest amounts of pedestrian traffic. Other bridges in this region include the Puente Francisco de Paula Santander, Puente de la Unión and Puente Tienditas, the bridge pictured to be depicting a blockade of humanitarian aid by Maduro’s forces last month.

Border crossing at Puente Internacional Simón Bolívar. Photo by Arjun Harindranath.

Further down the country, another widely used checkpoint between Colombia and Venezuela is to cross the Arauca river via the Puente International José Antonio Páez, which connects the Venezuelan town of El Amparo de Apure to Arauca, Colombia.

Lastly, despite being a slightly more difficult route, migrants also choose to cross via the Meta river in the Los Llanos region, where boats transport people from Puerto Páez in Venezuela to Puerto Carreño in Colombia.

But these official crossing points are by no means the only way to cross between Colombia and Venezuela. It is common practise to pay around $30,000 COP for a maletero, or a coyote, to accompany migrants across the border in non-regulated regions.

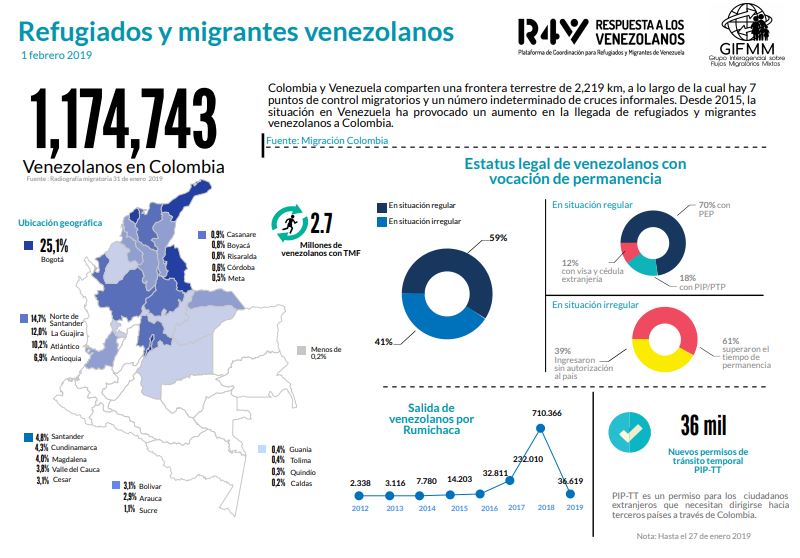

UNHCR statistics from January 2019 show that of the 1,174,743 Venezuelan migrants and refugees currently in Colombia, 59% are currently considered to have a legal status in the country, whereas the status of the remaining 41% is considered illegal.

Venezuelan migrants and refugees in Colombia as of February 1, 2019. Infographic courtesy of UNHCR.

Upon their arrival in Colombia, migrants can expect to find a series of Points of Orientation and Attention provided by the UNHCR in all four official crossing regions except Los Llanos. Here, representatives assess the migrants’ situation in order to find out what types of services and aid are available to them. Legal advice and psychosocial support can also be given.

In Villa del Rosario, the UNHCR has set up a special Integrated Assistance Centre and a Centre for Primary Medical Attention. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) also runs a daycare centre for children and the diocese of Cucuta dining room feeds over 3,000 mouths per day.

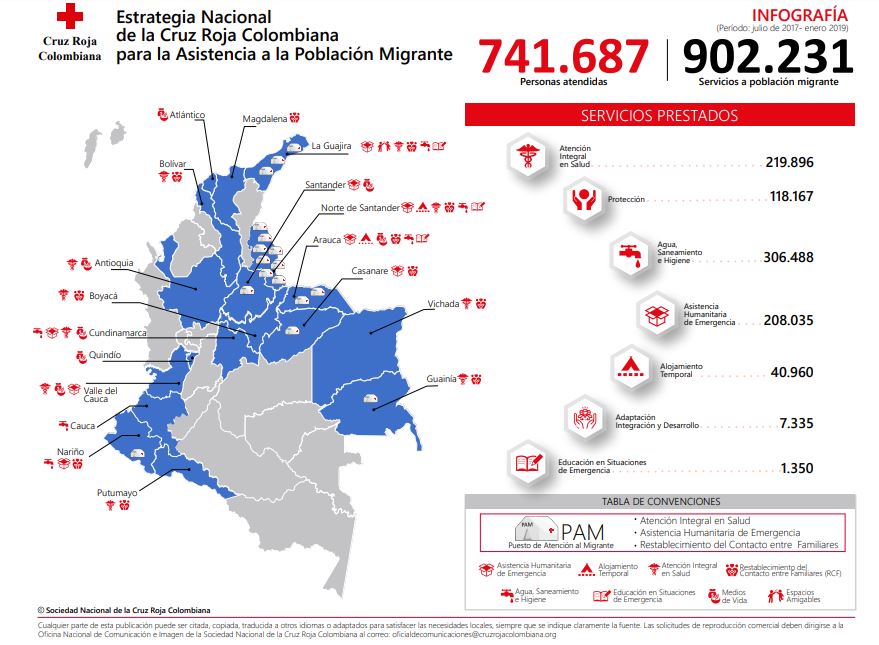

The Colombian Red Cross, which tended to 741,687 people between July 2018 and January 2019, also offers vaccinations and health check-ups for migrants from bases in caravans and at open-air stations. Beyond the border, the organisation also has stations along the pedestrian route from Cúcuta to other parts of Colombia, via the Páramo de Berlin, where emergency hygiene kits, food, clothes and practical advice for the journey are supplied.

Red Cross Colombia’s National Strategy for the Assistance of the Migrant Population. Infographic courtesy of Red Cross Colombia.

With regards to accommodation, various NGOs offer temporary shelters in border crossing regions and beyond. Locals have also given up their houses to provide refuge houses for migrants, without financial help from the state. In the city of Pamplona, for example, there are four refugee shelters still being provided by locals that can sleep between 100-150 people, despite being threatened to shut down on the grounds of being a public nuisance.

BRAZIL

The Venezuelan border with Brazil is far more limited when it comes to official crossing points, of which there is only one, which connects the Venezuelan town of Santa Elena de Uairén to the Brazilian municipality of Pacaraima.

Being the most northern region of Brazil, the remaining distance along the border with Venezuela is made up of savanna-like grasslands. Towns are few and far between, which complicates crossings in many areas. However, according to Brazilian daily Folha de São Paulo, as of 2017 there were at least seven illegal or unregistered crossing points.

Having entered Brazil through the town of Pacaraima, Venezuelan migrants can expect to find a centre on the border where biometric registration is carried out. Here, UNHCR representatives are supporting Brazilian authorities to register each arrival through a biometric scan of their irises. Their needs are assessed, they are offered a medical check-up and then presented with the options on offer from the Brazilian government to stay in the country. In Brazil, there is a governmental focus on the internal relocation of migrants and refugees, as well as labour reinsertion programme based on the professional skills of those entering.

According to a UNHCR report published in January, there are currently 13 UNHCR shelters located in the state of Roraima, spread across the towns of Pacaraima and Boa Vista, whose operation is run alongside Brazilian armed forces. Across these shelters, there is a total capacity to accommodate approximately 6,500 people.

GUYANA

When it comes to Venezuela’s third ‘border,’ the situation becomes much more complex. In fact, Venezuela claims almost two thirds of neighbouring Guyana’s land; a territory that is known as Guayana Esequiba. Despite Venezuela’s claim to the territory, it remains under Guyana’s administrative control.

With no defined border between the two lands, there are also no official crossing points. Speaking to Latin America Reports, University of the District of Columbia (UDC) scholar and Guyana specialist Paul Tennassee described the frontier as “porous.” However, this does not mean migration between the territories does not exist.

Migrants who decide to make the journey can choose from three options. Many take a boat from the Venezuelan city of Ciudad Guyana, travelling along the river Orinoco and arriving to the city of Charity in Guyana. Others choose to cross through the Venezuelan border with Brazil in Santa Elena de Uairén, travelling down to the city of Boa Vista and then entering the Guyanese town of Lethem via the Brazilian border. Alternatively, as Tennasee explains, migrants can also cross the border by foot at any point, but the rainforest terrain makes this journey extremely difficult.

Arriving in Guayana Esequiba, Venezuelan refugees and migrants are faced with a very limited presence of NGOs for assistance. Although UNHCR workers are limited and the organisation is working on “strengthening their response,” it does work with partners in the region. According to reports by local media, the Guyanese government has also been distributing food and other supplies to migrants and refugees, and local residents have offered them land to cultivate, as an alternative to relying on aid from refugee centres.

A CRISIS BEYOND BORDERS

Whilst recent focus has been firmly fixed on Venezuela’s borders, it is easy to forget that the country’s crisis has spread far beyond these invisible frontiers.

According to the UNHCR, the highest proportion of Venezuelan migrants in Colombia — 25.1% — can be found in Bogotá, not the border regions. After Colombia, the countries with the highest number of Venezuelan migrants in the world do not even border Venezuela. Peru, for example, which has approximately 506,000 migrants, is closely followed by Chile with 288,000, and then 221,000 in Ecuador.

Venezuelan refugees and migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean. Infographic courtesy of UNHCR.

“It’s not just a question of borders, but [the crisis] also extends across the region,” UNHCR’s Sarrado Mur pointed out.

More concerning, are the lack of resources dedicated to alleviating it. “In the majority of organisations we are aware that we have very few resources because not enough attention has been paid to this situation,” she said. “There are never enough solutions.”