Bogotá, Colombia – Bogotá’s inner-city enclave of San Bernardo was struck by a grenade attack last week, the fourth such attack in a month, even amid a security clampdown which has done little to dent a turf war between drug gangs.

In the latest incident on the evening of March 25, two men mounted on a motorbike tossed an explosive device into a group of people gathered on a street corner of the barrio, which lies in the heart of the Colombian capital’s troubled Santa Fe district. Three people were reported injured.

Three similar previous attacks in the same neighborhood claimed the lives of four people, with dozens injured, all in the space of five weeks, part of a feud between a Venezuelan crime group known as Los Venecos and a rival Colombian gang called Los Costeños, according to police statements.

The gangs were fighting over territory and drug trafficking, explained General Giovanni Cristancho, commander of the Bogotá Police, to El Espectador newspaper after an earlier attack.

“These explosions seek to generate fear, to affect the opposing group, and they kill innocent people, homeless people. It’s pure terrorism, there’s no other way to put it,” he said.

Repeated police raids in the barrio had captured 120 people and seized 20,000 doses of drugs, weapons, and grenades, he added.

But just hours after the latest wave of security operations in the barrio, with specialist police teams supported by military units, one gang brazenly launched the fourth grenade attack.

Capital conflict

“Suddenly it seems like Colombia’s conflict has come here,” local resident Carlos Sosa told Latin America Reports when we visited San Bernardo after the latest incident.

Sosa works part time in the Nuestra Señora de los Dolores church, in the center of the community. Originally from Venezuela, he has lived in San Bernardo for seven years.

The community always had suffered from insecurity, he said, but since December last year crime has reached new levels. The decline of the barrio was creating huge unrest, with people moving away.

“I’m guessing in recent years half the community has left. People are scared. And they are scared to talk,” he said.

Sosa pinned the underlying problems on widespread poverty. The church assisted with food handouts and a migrant shelter with space for 30 beds but had been hit by cuts to USAID funding.

“We’ve had to let staff go and cut back on the numbers of people we can support. We’re a poor church in a poor barrio,” he said.

Sosa pointed out the paradox of San Bernardo’s proximity to Bogotá’s main police command center, three blocks away on the corner of the Parque Tercer Milenio.

“People are selling and buying drugs in plain sight, and everyone is asking ‘why don’t they do something’ but nothing changes,” he said.

A new Bronx?

Outside the church, in a small park at the heart of San Bernardo dozens of people living in very precarious conditions were smoking and sharing bazuco, a street drug made from the residue of cocaine production.

Some talked to Latin America Reports on the basis their real names were not used. Even then, they were very reluctant to give details of the ongoing conflict in ‘Samber’, as the barrio is known colloquially.

At times the neighborhood felt abandoned, one said, with city officials turning up to “promise change and take a photo, then leave”. The barrio had also become a hub for people to buy small doses of drugs which can cost just 2,000 pesos (US$0.5), said another

“People fall into vice here, and San Bernardo is the place to come to buy drugs.”

He explained that drug dealing had intensified in San Bernardo after a notorious Bogotá slum, El Bronx, which for decades was a no-go area for police and city authorities, was “retaken” by 2,500 police and soldiers in 2016, with many buildings demolished.

As was documented by social organizations at the time, the Bronx operation simply dispersed drug gangs to other urban areas such as San Bernardo, five blocks away.

The “Bronxification” of new districts was a concern being raised by city authorities last week. In an official statement Bogotá’s mayor Carlos Galán vowed to bring San Bernardo under control.

“This new attack, like the previous ones in the same area, is the reaction of criminal gangs seeking to survive the sustained siege by the Bogotá Police on their structures in the San Bernardo neighborhood,” he said.

Epicenter of exclusion

The neighborhood would become the focus of an ambitious social intervention to address the multiple problems, with “48 billion pesos allocated to a comprehensive care plan” targeted at vulnerable populations including homeless people, victims of the armed conflict, indigenous communities and children and adolescents at risk.

The mayor’s office labelled San Bernardo an “epicenter of exclusion; the most excluded population in Bogotá” and promised to “turn it into a hub of inclusion”.

The crisis in San Bernardo put the security policy of Mayor Galan under the spotlight with recent figures showing homicides in Colombia’s capital climbed 11.9 % in 2024 compared to the previous year, with 1,204 murders recorded across the city.

Of these 90 occurred in the downtown district of Santa Fe, which includes San Bernardo, which when adjusted for population gives a homicide rate of 83 per 100,000; more than five times the city average.

Bogotá’s security chief César Restrepo played down the increase commenting to newspaper El Pais that 60% of the murder victims had criminal records and half of the homicides arose from contract killings related to territorial disputes between criminal gangs, which he also linked to increased pressure from the city authorities redoubling its actions against criminal organizations, with 300 gang leaders captured.

“There are two ways to lower the rate: making agreements with criminals so they don’t become violent [in exchange for allowing them to continue their criminal businesses] or dismantling crime, hitting them. We’re not going to make criminal agreements, so we went on the offensive,” he says.

He explained that the attacks by law enforcement against one gang mean that rivals then take advantage of that weakness to dispute territory.

Military-grade grenades

For many commentators, though, the troubles in San Bernardo stemmed from a lack – rather than an excess – of state presence, with some demanding a large-scale militarization of the zone.

“The war unleashed in San Bernardo cannot wait for short-term measures, we demand the authorities militarize the barrio now,” city councilor Oscar Vahos told City News last week. “This conflict between gangs has mutated into urban terrorism,” he said.

His point was underlined by news that grenades used in the recent attacks were of military origin and fabricated by Colombia’s main arms supplier, Indumil.

How these restricted military weapons ended up being used by drug gangs in San Bernardo would be subject to a “thorough investigation”, said security chief Carlos Restrepo calling on “those in charge of these types of armaments” – in effect the Colombian army – to take measures to ensure they do not fall into criminal hands.

The grenade revelation only underlined the power and resources of organized gangs in Bogotá. Many people we talked to in San Bernardo were doubtful that the current programs being planned for the barrio would fix the underlying issue of micro trafficking. At best, the problem would just be displaced.

“They clean up one area then the problem shifts somewhere else,” one said. “Usually somewhere close by.”

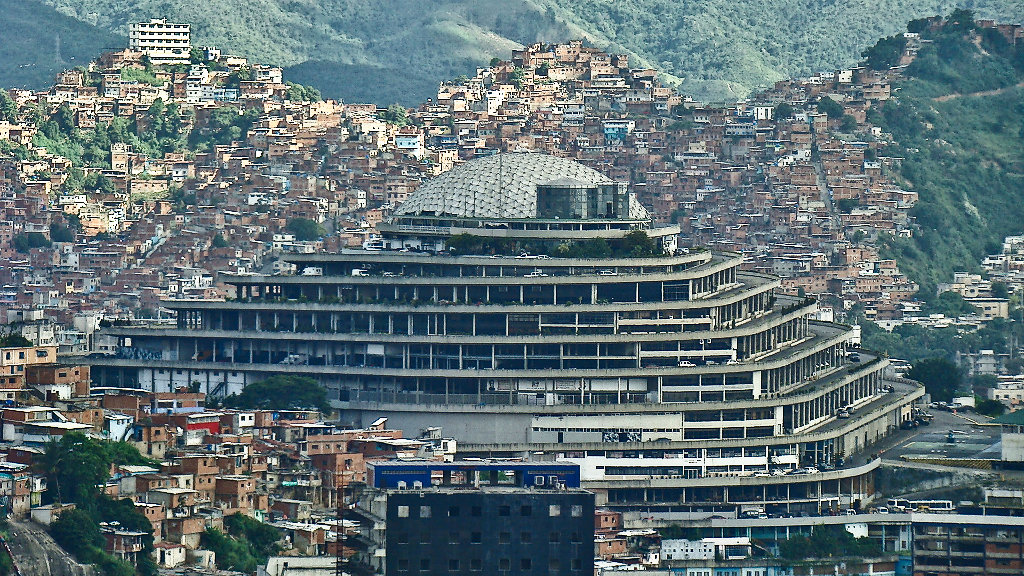

Featured image of a homeless person in the Santa Fe district of Bogotá, Colombia. Image credit: Steve Hide