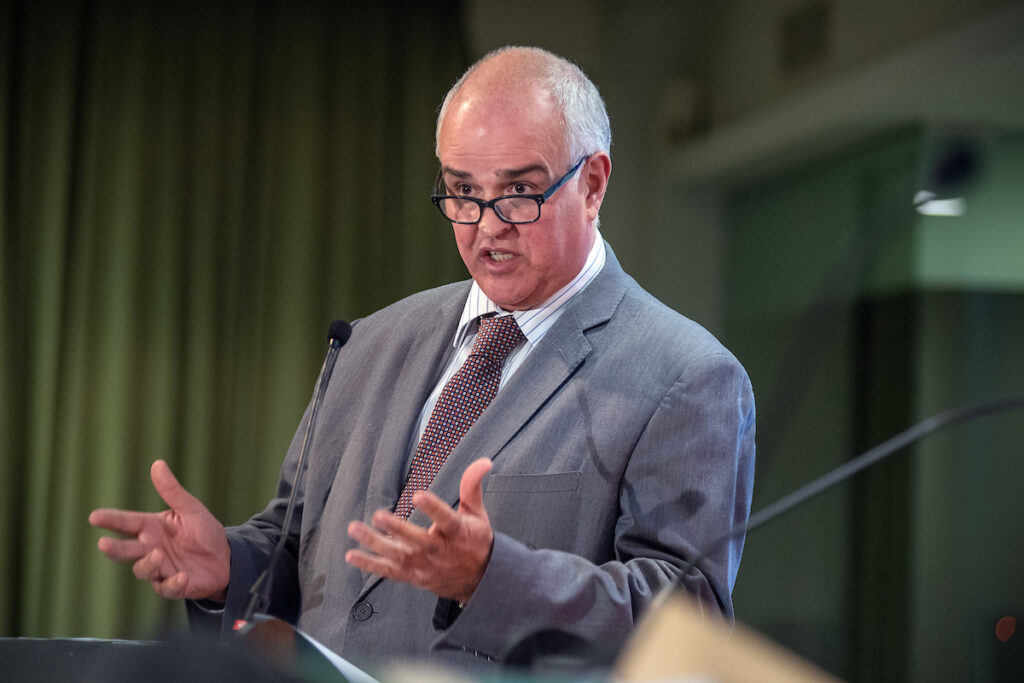

For the second time in six months, Costa Rica’s President Rodrigo Chaves avoided having his presidential immunity lifted by Congress — this time in connection with an investigation into alleged political proselytism, following complaints filed by the country’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE).

Lawmakers met on the afternoon of December 16 to decide whether to strip Chaves of his constitutional immunity. The president faces 15 complaints before the TSE alleging political proselytism.

In Costa Rica, political proselytism refers to the participation of public officials in actions that benefit a political party or involve them —directly or indirectly— in electoral political activities, which are prohibited under Costa Rican law.

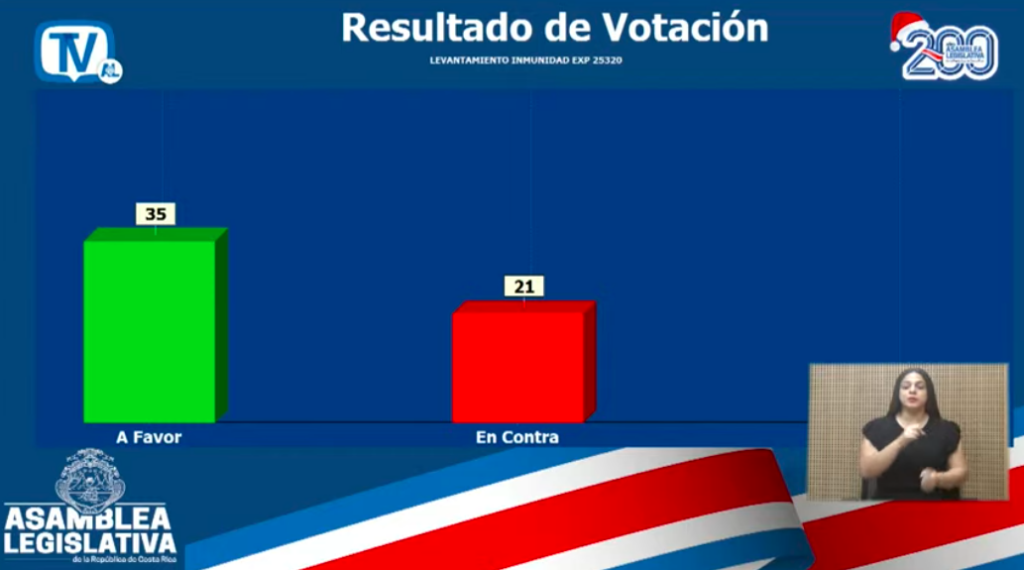

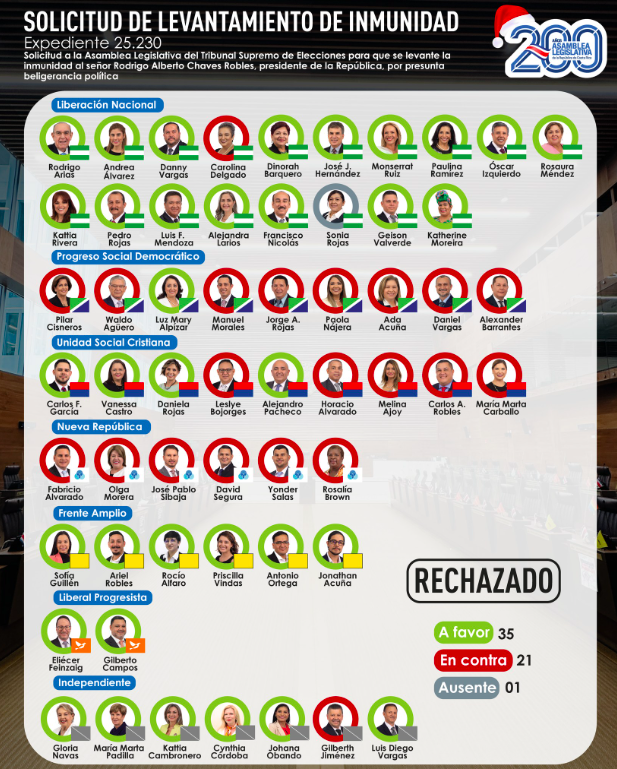

Although legislators serving on the Special Congressional Committee on lifting immunity recommended removing Chaves’ legal protection, the full legislature failed to reach the required 38 votes. During the extraordinary plenary session, 35 lawmakers voted in favor and 21 voted against.

Members of the special committee argued that “there is sufficient evidence for the Supreme Electoral Tribunal to investigate an apparent case of political proselytism and political bias.”

Opposition lawmakers reiterated that the process did not seek to remove Chaves from office, but rather to allow the administrative procedure necessary for the allegations to be investigated.

Alejandra Larios, a lawmaker from the National Liberation Party (PLN) and chair of the special committee, said that after reviewing the case file, the committee could recommend lifting the president’s immunity.

“The alleged acts are very serious. There is a significant risk of using public power to influence the popular will ahead of the February 2026 elections. The file submitted by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal deserves objective analysis. While some complaints were dismissed, others contain consistent evidence. These are allegations supported by sufficient proof, not only contained in the case file but also in the official communication channels of the Office of the Presidency,” Larios said.

“Public resources are being used to influence the electoral process by someone who is explicitly prohibited from doing so. The Electoral Code establishes an absolute ban. These are not isolated incidents; they are repeated actions,” she added.

President Chaves’ legal defense was led by attorney Daniel Vargas Quiroz, who argued that political proselytism is not regulated under Costa Rica’s Constitution.

“The Constitution, in Article 102, subsection five, refers to political bias, not proselytism. The distinction is not merely semantic; it is substantial. The Constitution uses precise terms because only clearly defined conduct can serve as a basis for sanctions. There is no legal definition in the current framework that allows a public official to be punished or prosecuted for proselytism, and the Electoral Code cannot fill that gap, as it does not have the authority to create crimes or independent offenses,” Vargas Quiroz said.

However, Article 146 of Costa Rica’s Electoral Code does prohibit public officials from participating in political or electoral activities during working hours and from using their position to benefit a political party.

The same article states that the president, vice presidents, public officials, members of the foreign service, and employees of any state or autonomous entity, as well as judicial and electoral bodies, are prohibited from attending political party activities or meetings, using the authority or influence of their office for the benefit of political parties, displaying party symbols on their homes or vehicles, or engaging in any form of partisan promotion.

Lawmaker Jorge Rojas López, of the Social Democratic Progress Party, said lifting the president’s immunity was unwarranted.

“There is no such proselytism. It is absurd to claim that saying the next government needs 38 lawmakers constitutes an offense. Did he mention a political party? This is being portrayed as partisan politics when it is simply how democracy works—through the will of the people to make the changes the country needs. This is an arbitrary action aimed at silencing a leader’s freedom of expression,” Rojas López said.

According to local media reports, it had been known since last week that Chaves’ immunity would not be lifted, as lawmakers from the New Republic party, led by Fabricio Alvarado, announced they would not provide their six votes in favor of the measure, arguing that it would affect the 2026 electoral campaign.

First case against Chaves involved alleged corruption

This is not the first time President Chaves has faced a request to lift his immunity. On July 1, Costa Rica’s Supreme Court of Justice also asked Congress to remove the president’s immunity so he could be tried on corruption-related charges.

The court approved the request with 15 votes in favor and seven against, after reviewing an accusation filed on April 7 by the Attorney General’s Office.

Prosecutors accused Chaves of the crime of concussion (an offense related to abuse of public office) stemming from an allegedly tailor-made contract awarded to the company RMC La Productora S.A. The contract involved communication, marketing, strategic consulting, message production, and public opinion trend analysis services for the Presidency during the 2022–2026 term, funded by a $405,000 donation from the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (BCIE).

On September 22, however, lawmakers rejected lifting the president’s immunity so he could face criminal prosecution. Only 34 legislators voted in favor, while 21 voted against.

This marked the first time in Costa Rica’s history that Congress voted on lifting the immunity of a sitting president. The Attorney General’s Office will wait until Chaves leaves office for the case to be heard by an ordinary criminal court.

Featured image credit: El Salvador’s presidency