This week, Brazil withdrew its offer to host a United Nations Latin America and Caribbean climate week that was due to be held this August in the city of Salvador.

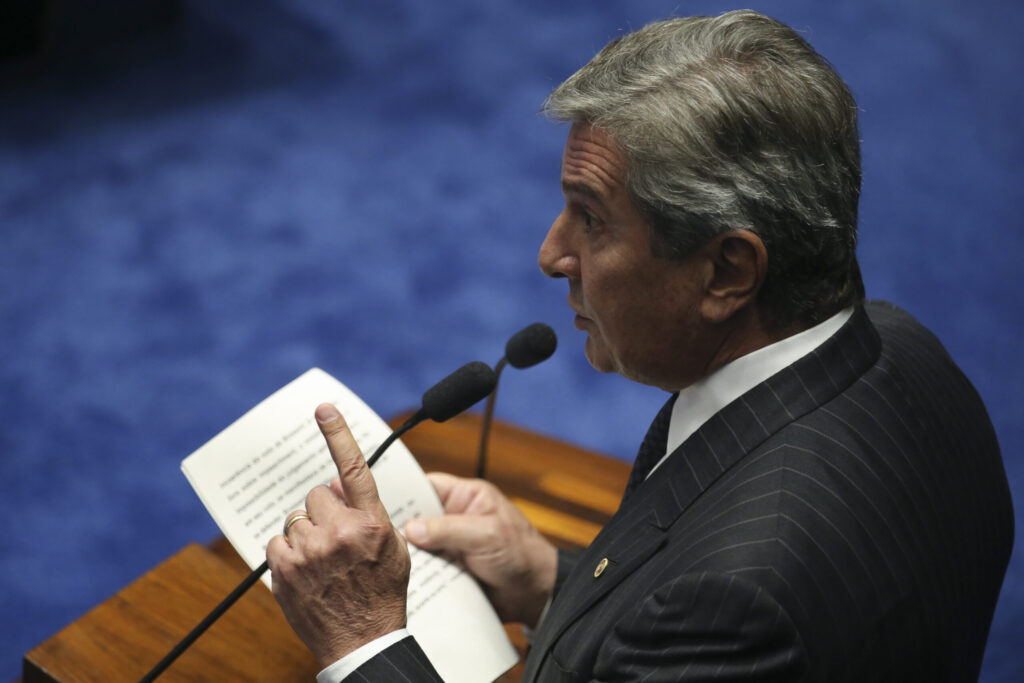

Bolsonaro’s current Environment Minister Ricardo Selles told national daily O Globo that it “didn’t make sense to host the event” without hosting the UN Climate Change Summit, which Brazil had already withdrawn its offer to host later on this year.

Last week, President Jair Bolsonaro also announced his intention to remove environmental protections from the Tamoios Ecological Station in the state of Rio de Janeiro, opening it up to tourist exploration in a bid to convert it into “Brazil’s Cancun.”

In the same week, the president fired self-confessed “militant environmentalist” Alfredo Sirkis, then-leader of The Brazil Forum for Climate Change.

At the time, Sirkis — who also co-founded Brazil’s Green Party — told Reuters that he believed his dismissal was linked to Bolsonaro’s efforts to form a climate change council that would act independently from Brazil’s federal government.

Minister Selles, who has previously described climate change as a “secondary issue,” denied accusations that Sirkis had been fired at his request.

Indigenous activists such as Chief Raoni Metuktire are actively seeking international support for the protection of Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, sections of which Bolsonaro plans to open up to the agribusiness sector.

Since the role of national environmental minister was established in 1992, all eight former occupants of the position have recently signed a communique warning against the threats facing Brazil’s rainforests at the hands of the Bolsonaro administration.

They have accused his government of a “constant, systematic and deliberate policy to deconstruct and destroy” the environmental policies that have been implemented in Brazil since the 1990s.

Former environmental minister Marina Silva, who contested Bolsonaro in last year’s election, also declared her concern that Brazil’s current administration would transform the country into an “exterminator of the future.”

Selles, who has previously outlined his plans to cut research funding for environmental NGOs in Brazil, as well as for scientists who, Bolsonaro argues, “always carries out the same studies,” pledged this week to instead focus his attention on combating urban environmental issues such as waste disposal.

Before becoming president, Bolsonaro previously shared videos of climate change deniers on his own social media. Not only does he make no secret of his own opinion, but also surrounds himself with people who share similar views, such as current foreign minister Ernesto Araújo, who in his personal blog describes climate change as a “Marxist plot designed to instil fear in the nation.”

One of Bolsonaro’s first moves as president in January was to grant the country’s agricultural ministry control of the creation and regulation of indigenous territories, previously the responsibility of the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI).

At the time, his opposition warned of the dangers this could pose to the environment, famously worshiped and protected by Brazil’s indigenous communities.