Bogotá, Colombia – On November 13, 1985, residents of the Colombian town of Armero were struck by catastrophe. A volcanic eruption triggered an avalanche of water, mud, and rocks which cascaded down the mountain and into the town.

Panic ensued as the townspeople rushed to escape the impending disaster. In the following hours, more than 70% of Armero’s population was killed; in total, some 25,000 people lost their lives, making it the world’s deadliest volcanic eruption in over 120 years.

Forty years later, Colombia remembers the Armero Disaster, an event that remains poignant not only for its immense human cost, but also due to the failure of the government to prevent it and the continued search for hundreds of missing children.

What happened on November 13?

At approximately 3:00 PM, the Nevado del Ruiz volcano, 80 miles west of Bogotá, started to erupt, spewing black ash into the air, which fell onto nearby towns including Armero. Within a few hours, the ash had ceased to fall and residents were told to stay calm and remain in their homes.

Around 9:00 PM, the volcano experienced an explosive eruption, melting the glaciers at the summit and triggering a cascade of mudflows, or lahars, made up of rock, debris, ash, and water.

The first lahar took roughly two hours to hit Armero, where residents had still not been told to evacuate. The mudflows, which were up to 30 meters deep and travelled as fast as 27 miles per hour, buried everything in their path.

Panic ensued as residents desperately tried to flee, with many of those evacuating on foot killed by cars speeding to escape the impending disaster.

Some 25,000 people were killed in a matter of hours.

Emergency response

As news spread of the disaster in Armero, emergency teams began to respond to the disaster. However, it took some 12 hours for rescue efforts to reach the town, with poor government preparation and a shortage of personnel, helicopters, and equipment hindering operations.

The lack of effective security at the disaster site also produced a wave of looting and disorder. International organizations, like the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders (MSF), also responded to the tragedy.

“The chaos was overwhelming due to the number of people who had disappeared, those who had been displaced, and those who were injured,” Pierre Marie Sarant, an MSF logistician who responded to the tragedy, told Colombian newspaper El Tiempo.

One of the most significant challenges of the tragedy was rescuing people who were stuck in the mud and debris. One girl, 13-year-old Omayra Sánchez, became an enduring symbol of the horrors of the eruption’s aftermath; trapped in the rubble for 60 hours, she eventually died of hypothermia and exhaustion before the world’s cameras.

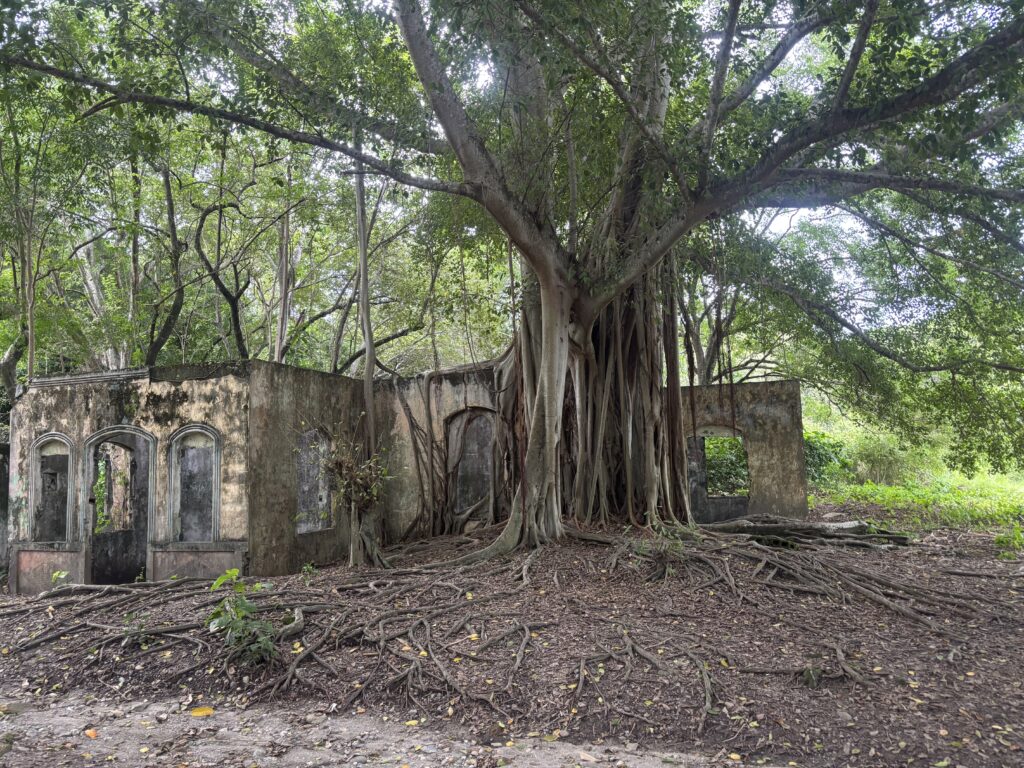

Today, Sánchez is memorialized at the ruins of Armero.

Missing children

While the international media concentrated on Sánchez, hundreds of other children were also being victimized during the disaster’s aftermath.

Following the tragedy, more than 583 children were reported missing, vanishing without a trace. There is evidence to suggest that hundreds of them were trafficked and illegally sold for adoption abroad.

Today, families continue the search to reconnect with their lost children, with only four successful reunions happening so far.

The Creating Armero Foundation, founded by Francisco González, a survivor of Armero, works to connect adopted children to their families through DNA testing.

“Any child adopted in late 1985 or 1986 could be from Armero,” González told Reuters.

Government failures

Armero is also remembered as a salient example of how government incompetence can trigger tragedy.

The disaster is widely seen as preventable, with local officials repeatedly trying to persuade the state government to mitigate risks in the months before the eruption.

Ramón Antonio Rodríguez, the mayor of Armero, had repeatedly lobbied the Governor of Tolima to prepare for a possible eruption. Specifically, he petitioned regional authorities to destroy a natural dam which had formed eight months prior to the disaster.

Caused by a rock collapse, the dam had produced an enormous reservoir above Armero. Rodríguez warned that a volcanic eruption would lead the dam to burst, exponentially increasing the scale of disaster. But the governor rejected his petition, citing insufficient funds.

Later, when the eruption began, the regional and national government played down the risk. They instructed residents to stay in their homes and remain calm, wasting a two hour window for evacuation.

Today, Rodríguez is remembered as a martyr, refusing to leave Armero in the hours before the landslide hit the town, despite knowing what would happen.

In a phone call to his girlfriend, who was in the nearby city of Ibagué and begged him to join her, Rodríguez said: “No, I have to help all these people get out, and I’ll be the last one to leave.”

He died alongside thousands of his fellow armeritas.

Featured image description: Aerial view of the aftermath of the Armero Tragedy.

Featured image credit: The U.S. National Archives.

This article originally appeared on The Bogotá Post and was re-published with permission.