Medellín, Colombia — In July last year, Colombia’s Comptroller General’s Office reported that 85% of the gold exported from the country is illegally mined, with 66% of this clandestine mining taking place in ecological reserve zones.

The Comptroller Environment Delegate claimed, “Colombia is in the presence of an environmental massacre,” as the ecosystem is becoming increasingly affected by the toxic chemicals used by illegal miners to extract gold, as well as other minerals.

Unfortunately, Indigenous communities are often those who bear the brunt of the socio-economic and environmental impacts of illegal mining.

A 2020 study revealed that 20% of the Amazon’s Indigenous territories in Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Perú and Venezuela are now affected by mining, their land increasingly infiltrated by violence and environmental destruction.

“The valuation of the Amazon has changed,” Fany Kuiru Castro, member of the Uitoto tribe and the first woman in 38 years to be elected head of the Union of Indigenous Organisations in the Amazon Basin (COICA), told Latin America Reports. “Before, it was valued for the forest and the CO2 capture that decelerates global warming, but over the last decades it’s started to be conceived as a place where the wealth of minerals such as gold, coltan, diamonds, is more important than the air that is breathed.”

While Colombia’s governments have long-failed to combat illegal mining on Indigenous territories, Indigenous rights activists suggest former President Iván Duque’s administration had a particularly detrimental impact. Indeed, a report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) showed that illegal gold production in the country rose by 3% in 2020.

Gustavo Petro has been proactive in supporting Indigenous rights, becoming the first Colombian president to appoint an Indigenous leader as ambassador to the United Nations. But, after half a year in office, to what extent has Petro implemented concrete policies which will actively combat illegal mining and, consequently, provide tangible support to Colombia’s Indigenous communities?

The illegal mining problem

The UNODC estimates that illegal mining in Colombia generates around 7 billion Colombian pesos per year, with much of the clandestine excavation still untraced. The profitability of minerals such as gold, more valuable than illicit goods like cocaine, makes its extraction an attractive option for illegal armed groups.

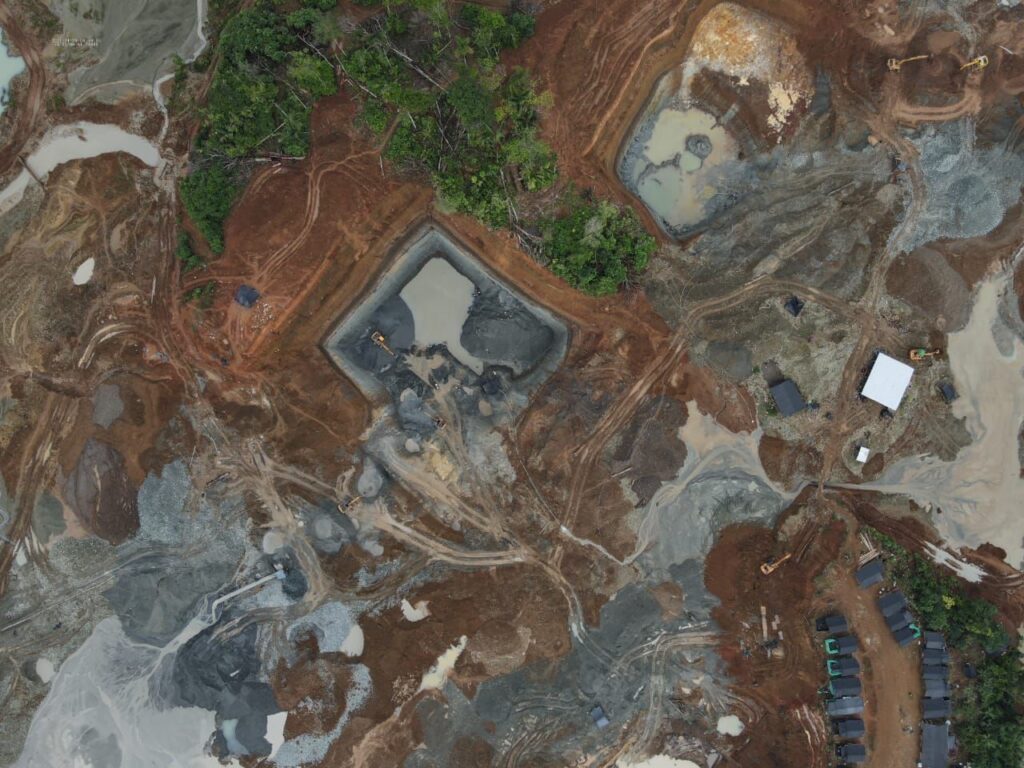

Below is a map showing areas in which gold mining and illegal armed groups converge.

In these zones, Indigenous communities face a two-fold impact. Firstly, extraction methods cannot be regulated for environmental safety, leading to the dissemination of toxic chemicals into the ecosystem relied upon by the native peoples.

These dangers are compounded by the threat to life such communities have faced, for years, from illegal organisations.

“One of the problems is that the largest culprits of affecting the rights of Indigenous communities are not necessarily formal, legal mining companies […] but instead, illegal mining organisations, criminal groups, and drug trafficking organisations, who’re really impinging upon the rights of Indigenous communities.”

Serigo Guzmán, Colombia Risk Analysis

Mauricio López, regional coordinator of the department of Nariño for NGO Ayuda en Acción, works on the ground with the Awá tribe, located in the southwest of Colombia near the Ecuadorian border. López has spent over 10 years in the region, previously representing Oxfam Colombia as well as other NGOs.

He told Latin America Reports that since the implementation of Plan Colombia, military forces pushed illegal drug trafficking activity centred in Putumayo towards Tumaco, a coastal city in the Nariño department. With money from illegal trade, they were able to expand the mining processes which already existed in the area, implementing destructive machinery with greater capacity to extract.

Detailing the environmental impact, López stated, “In the mining process heavy and acidic metals are used, such as mercury, that effectively contaminate water sources. […] This, combined with the widespread deforestation carried out in order to construct the plants, has caused a degeneration of ecosystems.”

“Gastrointestinal and skin illnesses began to develop due to the water contamination, which has provoked great vulnerability amongst the 35,000 people who make up the population of the Indigenous Awá territories,” he continued.

Plagued by disease, the Awá people have also been forced into overcrowded areas due to the contamination of rivers and food sources. López was keen to stress their seminomadic nature, meaning they migrate between regions seasonally, depending on fish and crop production. Now confined to certain areas, their food sources are severely limited.

In 2015, a visiting evaluation of the Tumaco region was arranged by CorpoNariño, an autonomous environmental organisation based in Nariño. They investigated an area inhabited by the Peña Caraño Resguardo Hojal la Turbia Awá community, which had experienced illegal mining activity.

CorpoNariño found “stagnant waters, […] soils not suitable for agriculture,” and “large extensions of deforested areas,” as well as impacts which have “affected the quality of water for human consumption and for fishing, which is one of the community’s means of subsistence.”

Seven years on, in a May 2022 study produced by Nariño’s Departmental Institute of Health, it was revealed that 77.4% of children under five had moderate acute malnutrition, and 25.5% severe acute malnutrition.

López stressed that the figures, relating to children who “are in a phase of cognitive and physical development,” are “extremely worrying.” He added, “These children are the future of the Awá culture, yet their future looks extremely bleak.”

When asked about the impact of former president Duque’s administration on the crisis, López pointed out that “the government’s ignorance goes back many, many years.” However, he said that Duque did not implement “mechanisms of prohibition against illegal mining,” and that “the problem intensified” during his presidency.

But how much blame can really be placed on Duque’s shoulders?

Duque’s mismanagement of Indigenous rights

Kuiru Castro, head of COICA, stated that “the Duque government tried to weaken the mechanism of Prior Consultation that guarantees the integrity of Indigenous territories and the autonomy that we as peoples have to decide on the projects that affect our territories.”

In 2019, the National Organisation of the Indigenous Peoples of the Colombian Amazon, OPIAC, and the Regional Amazon Bureau, MRA, came together to denounce the government for violating their human rights “to life, health, food security, culture and the environment.”

The statement damns the Duque administration, claiming “the current government does not have the will to attend to the current situation of the Indigenous Peoples, but it does demonstrate its interest in speaking in international scenarios about the protection of the Amazon and its inhabitants and, therefore, deceiving foreign and cooperating governments by requesting resources that will never directly attend to the communities.”

It does not appear that over the rest of Duque’s presidency, advancements were made to recuperate and promote the establishment of Indigenous rights.

Combining the year 2021 and the year 2022 up to August 7, when Petro took over as Colombian president, 336 social leaders, human rights defenders and signatories of the 2016 peace agreement were assassinated. This is according to statistics from Indepaz, Colombia’s Institute for Peace and Development Studies.

Duque’s Operation Artemisa, a top-down government campaign to combat deforestation, came under criticism for its forceful action, detaining and criminalising many Indigenous communities.

In September 2021, the house of a Nasa Indigenous governor, Reinaldo Quebrada, was seized by security forces and blown up with explosives, leaving at least twelve people homeless.

While the government accused them of occupying a buffer zone of Chiribiquete Park, a protected area, the Nasa tribe maintain that they lived there long before the area was declared a park zone.

Given the neglect felt by Indigenous communities throughout Duque’s time in power, Petro arrived in office with an opportunity to spark meaningful change.

Gustavo Petro: a saving grace?

Petro has seemingly championed Indigenous rights from the get-go, making history by including three Indigenous leaders in his cabinet. He appointed Leonor Zalabata Torres, a female Arhuaca social leader, as Colombia’s ambassador to the United Nations, inspiring much hope among Indigenous communities across the country.

In October 2022, Petro successfully passed the Escazú Agreement through Congress, which guarantees open access to information on State or private projects with environmental impacts. It establishes criteria for the protection of activists and environmental defenders in Colombia, giving local communities a voice during decision-making phases.

This is a statute that failed to pass through Congress under Duque, symbolic of a shift in governmental focus and, more specifically, of Petro’s desire to empower rural and Indigenous groups.

Just two weeks after coming to power, Petro announced measures to tackle illegal mining, proclaiming, “We will seek the legal path for this, it must be expeditious and headed by a single institution. Illegal extraction plants that are found will be immediately blown up.”

Kuiru Castro expressed her hope in Petro’s policies, stating, “President Petro, from his first days in office, has shown a different attitude towards [illegal] mining activity, because it has to be stopped.” She emphasized that the government must monitor “the number of mining exploration and exploitation plants, and the natural resources that are extracted in an uncontrolled way.”

We spoke to Sergio Guzmán, co-founder of Colombia Risk Analysis, to try and gauge the extent to which Petro has improved the political situation of Indigenous communities.

He began by noting that since Petro came to power, “he’s made sure to include Indigenous representation much more overtly as part of his government agenda. I think that, in a way, is very symbolic and very significant.”

“But one of the problems is that the largest culprits of affecting the rights of Indigenous communities are not necessarily formal, legal mining companies [whose influence can be monitored by the Escazú Agreement]. But instead, illegal mining organisations, criminal groups, and drug trafficking organisations, who’re really impinging upon the rights of Indigenous communities.”

Guzmán also highlighted that he doesn’t believe Petro’s Total Peace plan “is providing a dividend for Indigenous communities, at least not immediately in the negotiation stage, because the indicators of violence in rural areas have not improved, and the ability of the State to exert control of the territories and uphold their rights as citizens is questionable, at best.”

The plan involves the descaling of military action against illegal armed groups, allowing them more freedom to roam while peace talks continue.

López agreed on this being a hindrance in the short-term, stating, “In the changeover of governments, from Duque to Petro, these [Awá] territories are beginning to suffer humanitarian crises again, because groups of narcotraffickers and some FARC dissidents are trying to retake the territories to re-establish drug and arms trade routes.”

López said that in the last six months, 39 Awá Indigenous leaders have been assassinated, and approximately 5,700 tribe members have been displaced due to violence.

“Unfortunately, so far, under Petro’s government, there have not been substantial improvements in Nariño. The figures of displacement, murder, and malnutrition in these territories over the last few months is extremely worrying. Although international agreements have been signed, these are yet to materialise into efficient political action at a local level,” he explained.

Indigenous resistance

López said that “some [Awá] manifestations, such as roadblocks, have begun to take place in order to demand attention.”

Guzmán also referred to cases of Indigenous protests, stating, “the government’s policy against the extractive sector has empowered communities to take over some of these ancestral rights by force, which is something we’re seeing in places like Caquetá, and elsewhere, where Indigenous communities have carried out land grabs and kidnapped members of the police force and company representatives.”

At the beginning of March, a group of rural protesters including Indigenous tribe members seized a Chinese-owned oil plant, run by British firm Emerald Energy. The locals claimed the oil extraction company caused environmental damage in the region and were demanding funding to repave a 43 kilometre stretch of road connecting Los Pozos to San Vincente del Caguán.

Emerald Energy has since suspended activity in the region, and two people died during the protests.

Guzmán pointed out that such protests may “lead to push back from the extractive sector and other actors that are going to want the next government to act more decisively against Indigenous communities,” adding, “it could also materialise in divestment from these areas which would affect the local economy.”

Petro now faces a balancing act between a demand for economic growth in a country hard-hit by the pandemic, and the need to protect the land and rights of Indigenous peoples, bringing to the forefront a centuries-old clash of cultures between extractive economies and Colombia’s native civilizations.

“The relationship that Indigenous peoples have with territory is hardly comparable to the relationship that Western society, or capitalist society, has with its territory,” said Kuiru Castro from COICA. “For us, territory is more than just the space in which we live, it is the origin of our ancestors, it is the sacred place that allows and guarantees coexistence.”