Voting is an integral component of democracy, but the freedom to choose whether or not to do so is an individual’s right. Or is it? Across the globe, 22 countries have obligatory voting laws, and of those, 11 are in Latin America.

As Latin America became increasingly industrialized in the early 1900s, citizens migrated to cities in large numbers to find work. This led to the creation of leftist trade unions and workers’ parties, which were easily mobilized and had a high voting turnout rate, putting right-wing leaders in danger of losing their grip on power. By making voting compulsory, explained a study by Gretchen Helmke and Bonnie M. Meguid from the University of Rochester, it forced the right-wing “rich and content” support base to head to the polls to counteract the rise of the left.

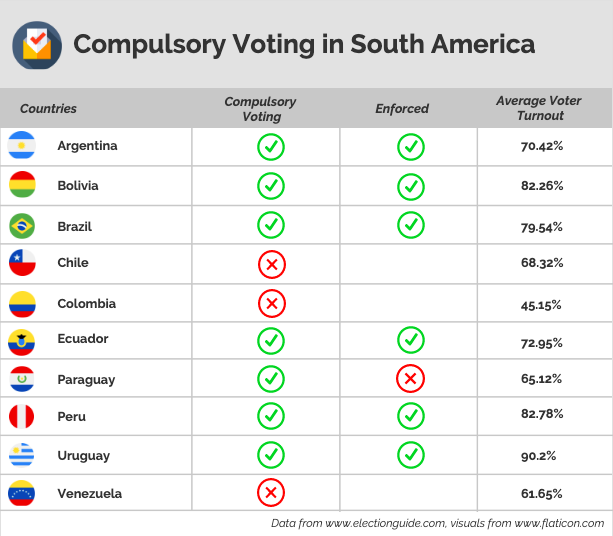

Voter turnout in countries with compulsory voting laws can vary by up to 40 percent, depending on the severity of sanctions for individuals who don’t vote. Bolivia — where voting turnout is almost 90 percent — has the most severe sanctions in the region, requiring citizens to provide proof of voting certificate to carry out procedures in state entities or public banks for up to three months after elections. In Costa Rica, voting is obligatory but not enforced, resulting in an average turnout rate of around 65 percent. Voluntary voting in Colombia, on the other hand, means that just 45 percent of citizens take part in electoral voting.

What are the advantages of compulsory voting?

Obligatory voting increases voter turnout. In theory, this would encourage people from lower socio-economic backgrounds to participate, resulting in a government selection process that better represents the population.

In practice, forcing people to go to the ballots does not force them to vote. For individuals who do not wish to vote for any candidate, they can submit an empty envelope (blank vote) or a voting paper that is invalid in some way (spoiled vote), which can either be accidental or intentional. This may appear counterproductive, but in fact it supplies the country with important data, said Ben Raderstorf, a non-resident fellow at inter-American think tank The Dialogue in conversation with Latin America Reports.

“Submitting a blank or spoiled vote is an indicator in and of itself, especially in polarizing elections” he explained. “Not voting at all doesn’t capture that in the same way – it’s easy to dismiss not voting as apathy, whereas [a blank or spoiled vote] is a clear sign of voter discontent against the system.”

Read more: Where do Bolivia, Uruguay and Argentina stand after recent elections?

In Argentina, citizens themselves often support compulsory voting. According to Télam, a private survey from August showed that 75 percent of Argentines would vote even if it wasn’t compulsory, and that half were actually aware of the candidates’ proposals. Latin America Reports spoke to Agustín Segura, a 26-year-old student from Argentina, who explained that it highlights how important it is to participate in the democratic process.

“Education is politics, talking out loud is politics, me talking with my family over dinner is politics,” he said. “Politics is day-to-day life, not just people wearing ties who are shut up in a room making decisions about what is going to happen in the country. That is what would happen if voting wasn’t compulsory.”

He added that the sanction should be more severe to get people to the ballot boxes, as the cursory fine of 50 Argentine pesos ($0.84 at the time of writing) isn’t enough to dissuade people from not voting.

“If the vote isn’t obligatory, it detracts from the importance of it,” he said. “[Voting makes the] power fall on the people and not the politicians. Making voting voluntary implies that the role a person or community plays by voting isn’t consequential.”

Compulsory voting also changes the way an individual approaches elections, Manuel Martín, a 25-year-old state worker from Argentina told Latin America Reports.

“I think that every time you go and vote, you have to reflect on your life, your plans, and about the different governments and electoral platforms that there are,” he said. “Even though I’m not that political, […] it brings it into the personal realm,” he added. “Because voting is obligatory, it is conditioned into us, which I think is something healthy and positive.”

What are the pitfalls of obligatory voting?

In most countries, voting is not obligatory. In 2012, Chile changed their voting system from obligatory to voluntary, which brought with it the expected drop in voter turnout, which currently averages at just under 50 percent. Although compulsory voting increases voter turnout, it also raises questions on democratic freedom, added The Dialogue’s Raderstorf.

“There is a certain discomfort on the obligatory part of it,” he said. “It’s the worrying idea that you can fine someone for not participating in the democratic process, it feels regressive, a tax on people with fewer resources, or less ability to engage.”

Read more: Bolivia’s 2019 presidential elections according to voters

This is also linked to another argument against compulsory voting, which is that people who are politically disengaged and uninformed might vote at random or based on arbitrary data, meaning that although turnout is high, the results are not truly representative of the population.

“[If it wasn’t obligatory], I wouldn’t vote,” said Augustina Santos, a 30-year-old teacher from Uruguay. “It’s a right that I should be grateful for, but politics has never held any interest for me. Compulsory voting means that more people will go and vote, but they’ll vote without knowing anything.”

Negative opinions towards obligatory voting are often held by middle and upper-classes, despite the fact it was originally implemented to keep these groups in power.

“It all cancels itself out, it creates a healthier democratic center,” Raderstorf said. “The elitism of an educated political class to believe that compulsory voting is hurting the masses — I think that reeks more of bias and a belief that poorer or less interested voters don’t matter as much.”