Policing strategies and security initiatives have developed massively in the last few decades. New technology and data analysis have cut down much of the time-consuming drudgery of police work and allowed officers to take already-crunched information and use it to refine and focus their efforts efficiently.

These technological advances, however, are not reflected in Latin America, where policy makers tend to lean on upping police presence and brutality as a deterrent.

Referred to as mano dura (iron fist), these extreme security policies have been proved in many countries in Latin America to actually increase levels of violence. Why then do governments keep falling back on it, and what are the alternatives available?

According to the Igarapé Institute, a Brazilian think-and-do tank, mano dura policies can be condensed into three groups: “Repressive measures against low-level crimes and criminals, the reduction and suspension of legal safeguards, and the severe use of military forces and police deployment.”

These policies have been used extensively across Latin America without success. In Mexico, for example, the “war against drugs” was implemented by then-president Felipe Calderón in 2007, but by the end of his term in 2011, Animal Politico reported that organized crime groups had grown by 900% and a United Nations development study revealed that homicide levels had increased from eight per 100,000 residents to 24.

The UN study also highlighted cases of mano dura in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, stating that “in terms of violence and crime, these policies generated negative results, intensifying violence in the three countries. They increased gang-based crime, including a rise in kidnapping and extortion.”

Despite increased police violence correlating directly with increased criminal violence, mano dura policies are still being implemented across the region.

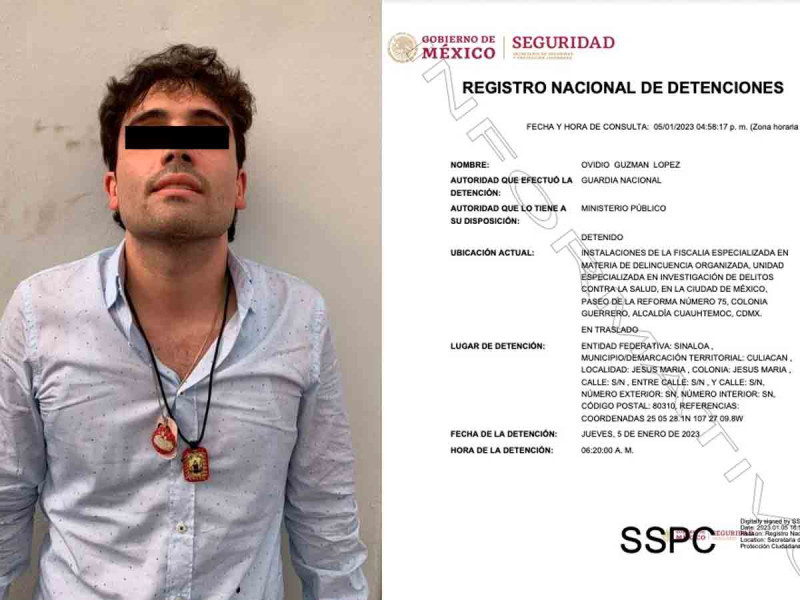

Even Mexican President Andrés Manuela López Obrador (AMLO), although creating a National Policy of Peace and Security, has subsequently developed a militarised national guard in an attempt to curb Mexico’s record-breaking crime rates.

A 2012 United Nations Development Program (PNUD) survey revealed that across Latin America, 87% of those asked somewhat agreed or very much agreed that the best way to fight crime was to implement harsher punishments. It also showed that one-in-three people would support the violation of the rule of law if it was a measure to fight crime.

Jair Bolsonaro, an ultra-right politician and overt sympathiser of Brazil’s authoritarian dictatorship, supported mano dura methods in his successful bid to become president, showing citizen’s approval of such a no-nonsense approach to crime.

Mano dura’s popularity is also linked to what the Igarapé Institute labels the region’s “chronic public security crisis.” With the prevalence of highly armed and highly dangerous organised crime groups, governments justify arming security forces and giving more leniency in the use of lethal force as a measure to protect them. If the police force remains safe, the thinking goes, then they can help keep civilians safe,

“The forces of security are always left in an inferior situation,” Argentina’s Minister of Defense Patricia Bullrich explained after a controversial new ruling loosening restrictions on police officer gun use was approved. “This is why we have created this new ruling which will allow security forces to protect people.”

This wilful ignorance and selective blindness to mano dura’s failed attempts keeps violence high and trust in the police force low.

As an alternative, data-driven policing has become more prevalent across the globe as advances in technology have facilitated both the amassing and analysis of crime data. In Los Angeles, Techcrunch reported, patrol officers work with digital maps that display the day’s “crime forecast.” Computers have been crunching through years of accumulated crime data which it can then use to predict where most criminal activity will take place, down to the city block.

“Every day, police wait in the predicted locations looking for the forecast crime,” wrote Andrew Guthrie Ferguson in his book The rise of data policing. “The theory: put police in the box at the right time and stop a crime. The goal: to deter the criminal actors from victimising that location.”

This technique has been used successfully in Latin America, reported The Economist. In Cali, Colombia in the early 1990s, then-mayor Dr. Rodrigo Guerrero used data analysis in a bid to reduce violence in the city. He realised that most violence took place in bars, late at night, a couple of days after payday. Guerrero restricted alcohol sales and gun use in these areas and managed to cut homicide rates by a staggering 35%.

According to Robert Muggah of the Igarapé Institute, 80% of the crime in medium and large Latin American cities takes place on 2% of the streets. By identifying these hotspots, national security forces could focus their attentions on the crucial areas without wasting time and manpower.

Despite the benefits of using a data-forward approach, an Igarapé Institute study on Citizen Security in the region showed that Latin America simply doesn’t have a systematic approach to gathering and analysing information.

This means it’s difficult to find data that is comparable at a national or regional level, and when data-driven policing is implemented – in just 12% of police security strategies – it is often on a very small scale.

The National Statistical Offices (NSOs) in the region often exhibit very different standards and abilities in collecting basic information, again making it more difficult to make solid comparisons and analyses.

Even if the government managed to accumulate more standardised data, the report explained, it wouldn’t necessarily give accurate information, as consistently low citizen confidence in police forces result in massive under-reporting of crime. NSOs report much lower levels of criminal activity than those shown through victimisation studies, and on average only about 30% of Latin Americans say they trust the police.

Criminologist Lawrence Sherman explained in his study Developing and Evaluating Citizen Security Programs in Latin America that due to these difficulties, many security programs in the region are designed without access to local data.

“If that is the situation, it is not an obstacle to solving an important problem,” he wrote. “It is the most important problem.”

Getting rid of mano dura and implementing data-driven policing across the board could make some important changes, but it’s not the only thing that has to change.

The Wall Street Journal reported one of the biggest challenges was to train better police officers. A more effective and more trustworthy police force will result in more true data as citizens who have confidence in the officers will report crime to them. However, with such a small percentage of Latin Americans trusting the police, this is no easy task.

“We know how to basically create a good cop,” Alejandro Hope, a former member of Mexico’s intelligence services and a security analyst told the WSJ. “It’s not a technical problem, and it’s not a lack of money. It’s clearly a political problem, which gives us both reason for optimism and pessimism.”

However, it’s going to be a difficult task to persuade not only governments, but also their citizens, that mano dura isn’t the most effective way to increase security.

Latin America spends 5% of their GDP on internal security, almost double that of the global average, and data-driven policing could be a way to decrease this using less police forces in a more focused way. General Patricio Carrillo, head of police operations in Ecuador, agrees.

“If we aren’t strategically anticipating crime,” he told WSJ, “we will always arrive late just to pick up cadavers.”