This year has been marked by political change and protest in Latin America. There have been surprises in Bolivia and Uruguay where right-wing presidential victories have brought an end to eras of leftist leadership, both of which lasted for over a decade. This conservative shift does not apply to the whole region, however, as Argentina elected a new left-wing president and local elections in some Colombian cities shook up the traditionally conservative status quo. We compiled a list of our coverage in a roundup of this year’s general elections in Latin America.

Guatemala

In the run-up to elections in Guatemala, voters who spoke with Latin America Reports were disenchanted with politics. Sandra Torres, former first lady and then-front runner in polls for the presidential vote, was implicated in a corruption scandal, while many candidates for congress, parliamentary members and mayors were victims of political violence or facing injunctions.

Read: Guatemala’s voters weigh in on 2019 election

In the first round of voting on June 16, voter turnout was low at 53 percent, and over 13 percent of votes were blank or spoiled.

Read: Who are the two remaining presidential candidates in Guatemala?

In the run-off held on August 11, Giammattei came out on top by a 15-point margin. Sandra Torres, no longer able to enjoy immunity from prosecution as a presidential candidate, was arrested for alleged campaign irregularities and corruption.

Giammattei is due to take office on January 14, 2020. In his victory speech, he set out the priorities of attracting foreign investment and promoting micro, small and medium-size businesses, while creating a guarantee fund for rural development. Previously director of the National Penitentiary System, Giammettei will take a hard stance on crime and has proposed to bring back the death penalty. Like Torres, he also opposes gay marriage, sexual education and abortion.

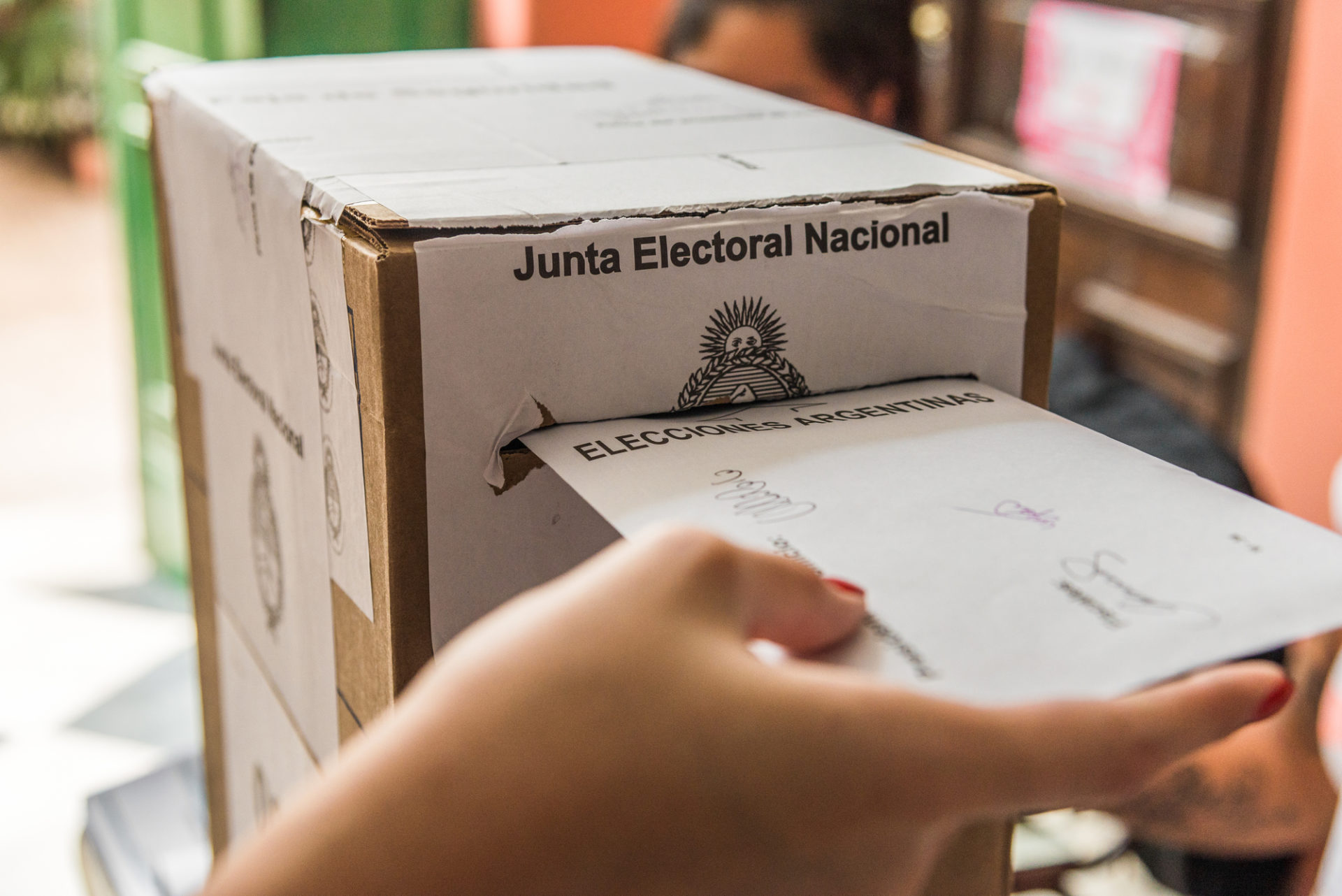

Argentina

The country’s economy was by far voters’ biggest concern in the run-up to Argentina’s presidential elections, which were held on October 27. So much so, that former leftist president Cristina Kirchner of the Citizen’s Unity Party, was able to accompany the campaign as vice-president to eventual victor Alberto Fernández, despite being embroiled in a corruption scandal. The Argentine population simply had too many immediate worries to be concerned with alleged political corruption.

Read: Economy takes center stage for voters in Argentina’s upcoming elections

Left-wing candidate Fernández emerged victorious, though by a finer margin than expected, by just a six-point advantage. He was sworn in on Tuesday, December 10, and gave a speech criticizing rates of hunger and poverty, calling out a need to “heal so many open wounds in [our] homeland.” The jab at the Macri administration and its failures was thinly veiled, but with the country in recession and burdened by around $100 billion in sovereign debt, Fernández is likely to struggle too as he begins his tenure on the backfoot.

Uruguay

Uruguay’s October presidential election was one of contrasts. On the one side was Luis Lacalle Pou, born into one of the most famous families of the Uruguay political elite. On the other was ex-guerrilla fighter Daniel Martínez, who represented the leftist Frente Amplio coalition: the incumbent force for 14 years. Lacalle Pou represented the Multicolor coalition; composed of eclectic politicians whose tendencies ranged from social democracy to the far right.

Read: Voters in Uruguay dissatisfied with political status quo

Lacalle Pou of Partido Nacional, despite coming second to Martínez with only 28.6% of the vote in the first round, eventually emerged victorious after bringing together various parties under the coalition Multicolor.

Read: Uruguay run-off election results indicate change in political status quo

Pou has tried to shift Partido Nacional away from conservatism to become more socially driven, thus aligning to some extent the party’s policy direction with that of Frente Amplio. However, the suggestion of putting military on the streets to lower crime levels indicates a willingness to adopt tougher measures to address the electorate’s concerns.

The greatest challenge Lacalle Pou will face once he takes office on March 1 will be reconciling the disparate parties that make up his support.

Bolivia

Despite recent economic prosperity and achievements for indigenous rights, former Bolivian President Evo Morales’ public image suffered because of his constitutionally dubious candidacy for this year’s October presidential elections. Despite losing out on the opportunity to run for a fourth consecutive term at the 21-F constitutional referendum in 2016, Morales changed the constitution to permit it anyway.

Bolivian citizens vote in the judicial elections in 2017. Photo courtesy of Flickr/OAS.

Read: Bolivia’s 2019 presidential elections according to voters

The elections sparked renewed nationwide protests after current President Evo Morales declared himself the outright winner, claiming to hold a 10-point lead over rival Carlos Mesa. The Supreme Electoral Tribunal stopped releasing preliminary results for nearly 24 hours on the day of the vote, inciting allegations of electoral fraud. Citizens both supporting and rejecting the potential for Morales to begin a fourth consecutive term as president clashed during demonstrations, resulting in at least 33 deaths and at least 1,500 injuries.

Read: Bolivia’s election protests divide the nation

The situation grew more tense upon the release, on November 9, of a preliminary Organization of American States (OAS) report indicating that there were reasons to suspect fraud. Morales agreed to new elections, but his announcement did little to stifle the protesters, who wanted the president to step down definitively. Later that day, the commander of the Bolivian Military, General Williams Kaliman, suggested that the president step down to restore “peace and stability and for the good of our Bolivia.” Morales then sought asylum in Mexico, leaving Senator Jeanine Áñez next in-line to be the interim head of state.

Read: Morales’ resignation leaves a vacuum of power in Bolivia

Áñez is a conservative Roman Catholic who represents the radical right of opposition in Bolivia. She made a statement of intent when she climbed the steps of Bolivia’s presidential palace, a Bible in her hands, proclaiming, “the Bible has returned to the palace.”

Read: What could a Morales-free Bolivia mean for its indigenous people?

In response to ongoing disturbances, Áñez issued an executive order on November 15 exempting the military from criminal responsibilities related to the use of force. This controversial order was later revoked and the situation has now settled more into political conflict than violent confrontations on the streets.

Áñez has passed a law appointing a new board that will set a date for a general election. However, other measures have not corresponded to what is expected of an interim president, such as undertaking significant foreign policy shifts.

Colombia

As was the case in 2011 and 2015, the run-up to local elections in Colombia were marked with high levels of political violence. In the electoral period this year, there were 34 instances of violence, including 16 murders, perpetrated against candidates and pre-candidates. Latin America Reports constructed a graphic illustrating political violence this year compared to 2015, and spoke with Angela Gómez from Colombia’s Electoral Observation Mission (MOE) to try and find out more about the issue.

Read: Political violence in Colombia after the 2016 peace agreement

Headlining the results on October 27 was Claudia López’s victory in Bogotá’s mayoral race. The Alianza Verde (Green Alliance) and leftist Polo Democratico Alternativo candidate became the first female and openly lesbian mayor of Bogotá, the position considered to be the second-most influential in the country after the presidency.

Read: Who is Claudia López, Bogota’s first openly gay, female mayor?

Another surprising election outcome came from Medellín, Colombia’s second-largest city and traditional, conservative Uribismo stronghold, where an independent candidate, Daniel Quintero, emerged victorious. The 39 year-old defeated the right-wing Centro Democrático candidate, Alfredo Ramos, by nearly 70,000 votes, demonstrating that change could be on the horizon for conservative Antioquia.

Read: Colombia’s key local election outcomes mark a shift away from political elite

Political analyst Sergio Guzmán explained that he views each city’s results as symptomatic of a growing national tendency for voters to move away from traditional elite-based parties and towards “more ideologically driven candidates.”

After a busy year for general elections in Latin America, 2020 looks likely to bring less political upheaval, with only two countries in the region with general elections due to take place: Guyana and Suriname. The Latin America Reports team will also be keeping a close eye on Bolivia, where the country’s interim president is due to call another general election.